“I’m afraid of Americans.” – David Bowie

American Psycho, the film by Mary Harron is a very intriguing adaptation of the iconic book by Bret Easton Ellis, both on and off the screen. Its journey to fruition is just as interesting as how it transfers the complex, psychological novel into a visual medium. It started in the hands of David Cronenberg, a director that I’m a big fan of and thought would be a perfect choice for the project. Johnny Depp had expressed an interest in the lead role and Cronenberg made a great first move and brought Ellis in on the project to write the screenplay version of his own book, which must have seemed like everything was moving in the right direction at the time.

However, Cronenberg put some very odd restrictions on scenes and didn’t want to include the numerous, integral restaurants and clubs that the characters frequent throughout the narrative. This caused the project to fall apart under this team, with Ellis even resorting to an elaborate musical number atop the World Trade Centre as a climax. He later admitted that he found the process difficult and was glad it wasn’t shot. Harron then came on board, with a script co-written with Guinevere Turner and cast Christian Bale in the titular role. She also attached Willem Dafoe and Jared Leto in supporting roles; a strong start.

Things were going smoothly but the project—and more specifically the lead role—was much sought after, so distributors Lionsgate Films were keen to hold out for a more famous actor, pursuing Leonardo DiCaprio above all others. Harron rightly refused to meet with him, saying she’d chosen Bale specifically as he was perfect for the part. DiCaprio was just coming off the back of Titanic and Romeo & Juliet and although he was just starting to mature, still had a very boyish look about him. Harron very rightly said that his fame and teen idol status would both detract from the film’s tone.

Lionsgate went as far as increasing the budget from $10 million to $40 million to meet DiCaprio’s fee of $21 million. He also shortlisted directors he’d like to work with that included Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese, and Danny Boyle. Lionsgate even jumped the gun and announced that DiCaprio had accepted the offer, which was swiftly denied by his manager. Stone was brought on board, who Harron stated was “the single worst person to do it” and I’m in total agreement with her there. He ended up not moving forward with the project after he was unable to agree on the film’s direction with DiCaprio, unsurprisingly.

Lionsgate went as far as increasing the budget from $10 million to $40 million to meet DiCaprio’s fee of $21 million. He also shortlisted directors he’d like to work with that included Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese, and Danny Boyle. Lionsgate even jumped the gun and announced that DiCaprio had accepted the offer, which was swiftly denied by his manager. Stone was brought on board, who Harron stated was “the single worst person to do it” and I’m in total agreement with her there. He ended up not moving forward with the project after he was unable to agree on the film’s direction with DiCaprio, unsurprisingly.

Besides, Stone had already made his own version of American Psycho in the form of Wall Street back in ‘87. DiCaprio left the project and has since said that he was unaware of the steps already taken by Harron and Bale. He would go on to have his own Patrick Bateman role in The Wolf of Wall Street, directed by Scorsese, the best and most suitable of his shortlisted directors, some 13 years later; this proving everything that Harron said right about his suitability for the part and restoring balance to the universe. Justice prevailed and Harron and Bale were brought back on board with the original $10 million budget.

The latter had kept himself free for nine months during all this, even turning down other auditions, confident that DiCaprio would eventually leave and he was right on the money. Bale was so committed that he spent several months working out by himself before he started a three hour, daily workout routine to achieve the athletic physique Bateman has. Now that the right people finally had the reigns again, they then had the difficult task of adapting a deep, intricate book. Harron and Turner’s discerning script focussed more on Bale’s performance and the black comedy of the narrative, elements that lend themselves well to the medium of film.

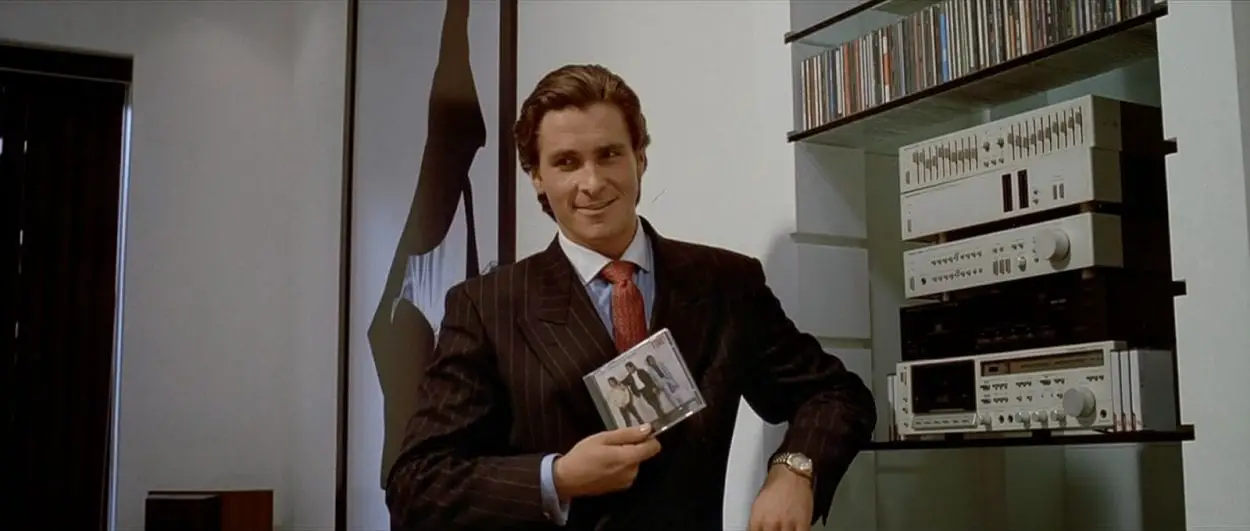

There are many genuinely hilarious moments throughout, some black comedy and some that capture the hollow, plastic, materialistically perverse ‘80s lifestyle Bateman lives. One where he’s always getting confused with other Wall Street bankers, as they all look the same and they fetishise the food they eat at high-end restaurants. As with most great films that have some humour in them, I find myself laughing out loud more than I do during most modern comedies. These moments, coupled with numerous memorable motifs, is what makes the film so compelling. Scenes such as Bateman’s morning routine, comparing business cards with his colleagues, and murdering Leto’s character with an axe in his living room whilst wearing a translucent raincoat.

This was not only the role that Bale was born to play but he has the perfect look for it as well. His ability to switch between dark, stoic moods to wild, eccentric outbursts is endlessly entertaining. You can tell Bale is having fun with the role but there are also few actors who have the range and skill to deliver such a performance, it could easily have fallen flat in a less talented actor’s hands. Dafoe and Leto are also great foils for him to spar with, their scenes with him being the most tense and enthralling. Justin Theroux nails it as Bateman’s vacuous best friend and Reese Witherspoon also put in one of her best performances as the embodiment of his shallow social life, in the form of his fiancé that he has a sham relationship with.

The dialogue is incredible, with so many quotable lines. A running monologue is also used to try and transcribe the psychological aspect of the book but this can only be used sparingly. Some lines were taken from the novel, some not. Either way, Harron and Turner deserve a lot of credit for a very witty script and how it’s delivered. Turner even has a small part playing one of Bateman’s victims and plays it well. It’s so important that this film is written and directed by women. In the hands of a male writer/director, the film would be extremely vulnerable to attacks about being misogynistic. However, as with most good films that come under fire for this reason, the purposefully chauvinistic elements are satire and a commentary on the issues themselves.

Music, both diegetic and non-diegetic, is an integral part of the film. Bateman has a peculiar affinity for pop music of the time and is very knowledgeable on the subject, which he likes to recount to his victims in a concise manner. Likewise, the perfect man was chosen to oversee the music in the form of my personal hero John Cale, a founding member of my favourite band The Velvet Underground. As a classically-trained musician, he’s an excellent choice to write the brilliant, biting score and being one of the godfathers of alternative music, he’s also the best man to pick the soundtrack.

Cale’s choices range from some of the best British artists such as New Order, The Cure and David Bowie, along with super cheesy yet likeable ‘80s acts like Huey Lewis & the News, Katrina & the Waves and Chris De Burgh. The music was crucial to this film that is suitably more style over substance, as the film was never going to be able to reach the depths of depravity the book plunders. Having read it myself, I can say that this is one of the rare occasions that the novel offers something the film cannot. In its pages, you’re privy to every one of Bateman’s thoughts. For example, every time he meets someone, he always lists every article of clothing that they’re wearing, including brand and style.

He does this compulsively throughout and after a time, you begin to realise that Ellis is using it as a shrewd technique to demonstrate just how tightly wound and crazy he really is. Harron does a good job of matching this with imagery throughout the film in various ways; using face masks, reflections and frosted glass. However, although subtle and appealing, it doesn’t quite have the same impact at getting the point across. As you can also imagine, Ellis has free reign to go into as much detail as he desires in Bateman’s sexual exploits, violent acts and killings.

Harron’s film, on the other hand, had to cut out about 18 seconds of footage from his ménage et trois scene with two hookers to avoid an N-17 rating and get it rated R instead. Harron cleverly side-steps most of the murders and violence with cutaways and subtle nods. This works well as sometimes it’s what you don’t see that’s more horrific than what you do. For example, seeing a model go home with Bateman from a club and then the next day, him opening his fridge to reveal her severed head wrapped in plastic inside. The other major difference from the book is the ambiguity of just how much of these killings, if any, he actually carried out and how much of this is all in his deranged mind.

It’s much easier in the novel to maintain this mystery throughout, whereas in the film it’s saved for a twist towards the end. This has drawn some criticism but again, I think this structure lends itself to the different medium as well. Instead, this is translated with numerous lines of dialogue throughout, where he explicitly says something about confessing his actions and the vapid people around either hear it as something else or don’t seem to hear it at all. This is a technique that’s as savvy as it is alluring. This comes to a head when Bateman kills a woman on the street and is pursued by police, leading to many more murders whilst escaping capture.

He ends up hiding in his office and calling his lawyer in a meltdown to give him a full and detailed confession. Despite his best efforts though, his lawyer simply won’t believe him and claims to have had dinner recently with one of his victims, throwing everything into confusion. We’re left with Bateman’s monologue saying that the punishment he deserves continues to allude him and that this confession to us, the viewer, has meant nothing. This ending raises the question of what he’ll do with his future and if he’ll ever be exposed as the psychopath he really is. Overall, I’d have to say that the book is superior as a piece of work. However, I think the film is a great interpretation, one that’s as good as it could possibly have been and goes hand in hand with the source material.

Harron’s sensibilities complement Ellis’s writing style perfectly and she deserves a lot of credit for seeing her specific vision for the project through to the end, despite the numerous hurdles in pre-production. Ellis has said that although Bateman as an unreliable narrator didn’t fully transition, Harron nailed the humour that was mistaken for blatant misogyny in his novel, so that’s a win in my book. It’s easy to see why American Psycho has gained a cult following, it’s the Clockwork Orange of its era. Ellis has since said that he felt that it didn’t need to be made and I can see what he means but personally, I’m really glad it was.