So: is Is That Black Enough for You?!?—the new Netflix documentary from film historian and writer Elvis Mitchell—“black enough for you?” It is for me and I hope for you: the film offers an updated, earnest, and impressively detailed analysis of African American cinema. While Mitchell takes 1970s cinema generally, and Blaxploitation films specifically, as his starting point, the film circles back to the early days of Oscar Micheaux to chart Black representation both on and behind the screen. It’s more an essayistic approach than a comprehensive history, but that’s the film’s strength: Is That Black Enough for You?!? nimbly charts the stereotypes and prejudices that motivated a brief, even incendiary, explosion of black talent onscreen in the 1970s.

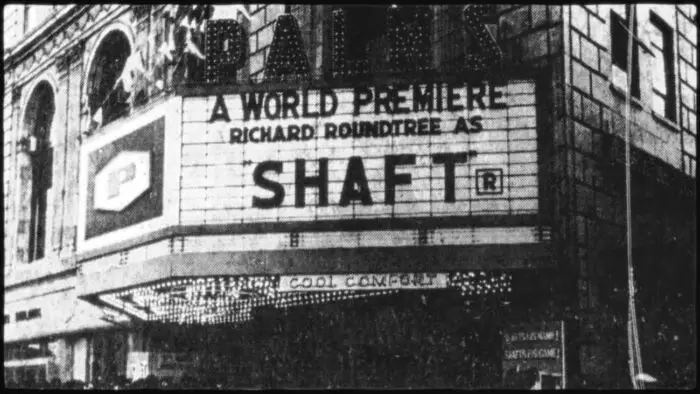

For Mitchell, a renowned critic, scholar, radio host, and film curator, the 1970s were both when he came of age as a moviegoer and the first time in history when Black men—and women—could be seen regularly on cinema screens. The popularity of Shaft, Superfly, Slaughter, and Coffy led to numerous sequels and imitations; meanwhile, more serious, if less overtly commercial fare like The Learning Tree studied the African American experience with an unprecedented realism and nuance. Even major studios were investing in star-studded dramas like Lady Sings the Blues.

But that moment seemed to end nearly as suddenly as it started. As the 1980s approached, the Blaxploitation era ground to a halt, and studios largely quit investing in Black talent and narratives both. To explore why, Is That Black Enough for You?!? relies predominantly on Mitchell’s expository narration—he is, after all, a writer—illustrated by an amazing array of curated clips and images from across the entirety of the 20th century. Micheaux and his masterpiece Within Our Gates is given its due, as is French director Alice Guy-Blaché’s recently discovered 1912 short A Fool and His Money, the first film to feature an all-African American cast. So too are the lowlights of Hollywood’s classical period: the relentless instances of Blackface, the subordination of Black talent to the periphery of narratives, the unyielding stereotyping charted so well by Donald Bogle. Moments perhaps taken for granted, like the usurpation of the all-time box office receipts record of The Birth of a Nation by Gone with the Wind, take on new and resonant meanings.

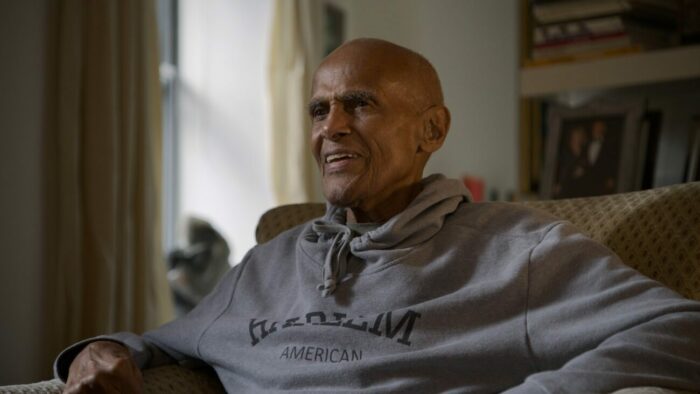

Especially interesting is Mitchell’s take on the less often examined period directly preceding the explosion of Blaxploitation films. Harry Belafonte—on-camera here as one of several interviewees—is cocksure and confident as ever in discussing his exile from cinema in the 1960s. Mainstream filmmaking could simply not accommodate his sex appeal and chose instead the polished and nonthreatening Sidney Poitier to star in prestige dramas designed to assuage white liberal anxieties. Meanwhile, filmmakers like Ivan Dixon, William Greaves, and Melvin Van Peebles were just beginning to take the reins in more radical films of their own making. (I love seeing Dixon’s magnetism, Greaves’ split-screens, and Van Peebles’ double-dolly all in the same film!)

Through this and the rest of the film, the editing—credited to Michael Engelken and Doyle Esch—is nothing short of extraordinary. Given the vast scope of Mitchell’s history, the work of tracking down and securing permissions for hundreds of individual clips, some from barely-seen films, all in brilliant high definition, is in itself a Herculean effort, but Engelken, Esch, and their team not only adroitly illustrate Mitchell’s argument seamlessly, they have some fun doing so, stitching together some nifty transitions. And to his credit, Mitchell also focuses on African American music (and to a lesser extent, fashion, art, and dance) and its impact on the cinema of the era, such as Isaac Hayes’ magnificent performance of the “Theme from Shaft” at the 1972 Grammys, replete with dancers decked in chainmail.

None of the history leading to the focus on the 1970s is necessarily new, but Mitchell presents a clear thesis: the more experimental work of Greaves, Dixon, and Van Peebles was largely left by the wayside in the wake of the commercial hit that was 1971’s Shaft. The Gordon Parks-directed breakaway hit that (despite its having been written originally with a white lead) led to multiple sequels, a television series, several novelizations, a 2019 reboot, and dozens upon dozens of imitators. Mitchell follows Shaft with Van Peebles’ truly revolutionary Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, a truly independent film made on a shoestring and promises that preceded Shaft by more than four months.

Van Peebles, who passed away last year at age 89 would have made an excellent interviewee. But he made his own documentary on African American cinema, Melvin Van Peebles’ Classified X, which I equally highly recommend, in 1998. His son, Mario Van Peebles, brilliantly documented the making of Sweetback in his 2003 docudrama Baadasssss! The list of interviewees is otherwise impressive: Harry Belafonte, Charles Burnett, Samuel L. Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg, Laurence Fishburne, Zendaya, and others each offer their distinctive perspectives on their own relationship with films of the era.

The interviews here serve largely only to support Mitchell’s thesis and help explicate some of the content. In other words, they’re secondary—tertiary, perhaps—to Mitchell’s narration and the clips themselves. But they never feel superfluous, and even after five decades of Samuel L. Jackson onscreen I’ll never tire of his wisecracking humor and keen insights. The interviews also supplement some of the films of the era that didn’t fit the Blaxploitation paradigm, from Cornbread, Earl and Me to Cooley High and Claudine to Coonskin.

The documentary’s title—the phrase “Is That Black Enough for You?!?”—quotes Ossie Davis’s Cotton Comes to Harlem, where it’s used multiple times in various iterations. It’s a phrase that Davis borrowed from Black revolutionaries, wrote into the opening-credit ballad sung by Melba Moore, and works at least three times into the film’s dialogue, each time by a different character and with a different meaning. Later, Gamble and Huff turned the phrase into a Billy Paul hit that Schoolly D would sample. It’s a phrase that keeps coming back. And it perfectly encapsulates Mitchell’s presentation.

With so much ground to cover, and all of it covered thoroughly, Is That Black Enough for You?!? feels a but rushed near the end. Mitchell argues that the end of the Blaxploitation era came about when its signature movements were paid homage by John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever as “an off-white take on Black cool” that hit the mainstream. At the same time, the white male leads who’d spent the 1970s brooding about as flawed antiheroes suddenly reclaiming more heroic roles. The examples given—Warren Beatty in Heaven Can Wait, Kris Kristofferon in Convoy, Burt Reynolds in Hooper—strike me as a little cherry-picked. Mitchell concludes with a nod to the elegant, eloquent films of the L.A. Rebellion to eulogize the end of the era. While I know a film like this requires a massive amount of research, permissions, writing, and editing, I’d love to see this argument for the end of the era expanded—or for Mitchell’s take on the New Black Cinema of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Come on, Netflix: pony up!

Speaking of which: a film like this, excellent as it is, can only serve to illustrate the damning paucity of historical African American cinema on a major streaming service like Netflix. While in the wake of the George Floyd murder and subsequent worldwide protests, some services (for a time) made the work of African American auteurs free to subscribers. In the past Netflix has made some excellent content, such as Kino’s Pioneers of African American Cinema, available to stream, not. a. single. one. of. the. films. mentioned. above. is currently available to stream on Netflix.

That’s right: not. a. single. one.

Mitchell argues that “representation is revolution.” Fair enough, and his documentary makes that point well. The 2022 Hollywood Diversity Report suggests, at least at the moment, some increasing representation both onscreen and behind the camera. And Netflix has produced some excellent content by and about African Americans in recent years. But it’s a shame that to watch what Mitchell has watched, you’ll have to be something of a private investigator yourself, checking out every other streaming service including perhaps Brown Sugar and even the increasingly diverse Criterion Channel, YouTube, your public and university libraries, and yard sales for the actual films discussed in Is That Black Enough for You?!?