We’ve all seen the news stories featuring what Charlotte Cooper famously coined “headless fatties”—those stock photos or clips of headless fat people used in nightly news stories about ob*sity. In those stories, fat bodies are portrayed, but not fat people. That is, the whole person isn’t visible to us in either the image or the narrative; they are distilled down to only their weight. This is not the case with Jeanie Finlay’s documentary Your Fat Friend, which follows Aubrey Gordon’s rise from what could have been a one-off anonymous blog post to an acclaimed author and beloved podcast host.

Six years in the making, Your Fat Friend, in fact, follows the steps to put a face to the ideas and a name to the anonymous blog post that skyrocketed Aubrey Gordon to being one of the more well-known advocates for fat people in the United States. Gordon’s first blog post “A Request From Your Fat Friend: What I Need When We Talk About Bodies” was published in 2016 under the pseudonym “Your Fat Friend,” from which the documentary takes its title. As Finlay documents, within weeks, the blog had 30,000 reads, so Gordon continued to write from her personal experiences of fatness in a country that not only values but worships thinness while her readership grew exponentially.

The documentary charts Gordon’s experiences with her new-found following without flinching. In the director’s opening remarks, Finlay tells viewers that Gordon explicitly told her that she could film her from any angle she liked, and Finlay notes how rare it is to have someone allow that kind of freedom. Your Fat Friend makes use of Gordon’s openness not only by employing sweeping shots of her in swimsuits as well as focused shots of arms and stomach, but also through the lens of Gordon’s personal experiences with becoming simultaneously loved and hated for her public posts about anti-fat bias as it manifests in her public life and her daily life with her family.

As Gordon watches her readership grow, she delights in hearing from other fat people that they are grateful to her, but she also receives hatred and threats. Your Fat Friend presents those comments on Gordon’s posts verbatim—including dictates that she should just die already and threats to kill her. Deftly inserting these comments at a point in the documentary when viewers have already gotten to know Gordon, Finlay makes it all the more unfathomable that people would wish her harm or seek to inflict harm on a person simply trying to explain her experience of living in a fat body.

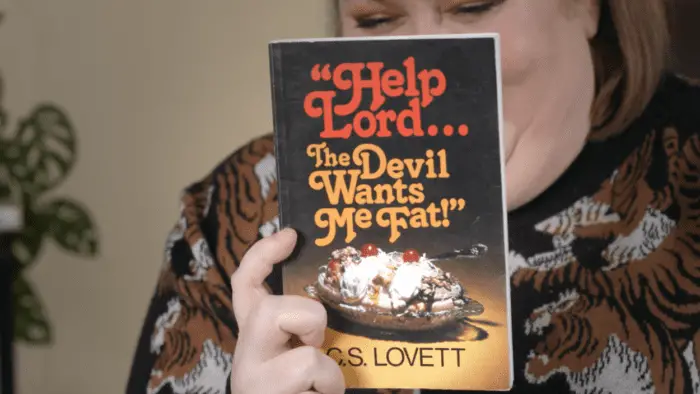

A good deal of that experience includes her attempts to lose weight. Gordon sorts through and displays some of the favorites of her diet book collection, many which feature celebrities or make use of religious themes as she points out how few diets work and how much money the diet industry makes each year by selling the idea that there is always a path to losing weight. At one point, Gordon, noting how many diets not only fail but end up causing people to weigh more than they began, says that people need to look at folks like her differently: instead of looking at them and wondering why they don’t put in the effort to lose weight, look at people like her and think that person may have put in a great deal of effort. And all those efforts may be why that person weighs what they weigh.

In addition to criticisms of the diet industry writ large, Your Fat Friend poignantly makes use of Gordon’s willingness to describe her own experiences with anti-fatness and the world not being made for fat people. Her experiences range from her talking about the terror of being on a plane or bus and knowing that people don’t want to sit beside her, to worrying that a chair may not hold her, to having people confront her about food choices as the grocery store. In these ways, the audience simultaneously learns about Gordon, her experiences as a fat person in the world, and all the different ways anti-fat bias features in daily lives like hers and those of other fat people.

In fact, the rich backstory of Gordon that Finlay incorporates is another way the documentary challenges the notion of the “headless fatty.” While the online trolls seem able to see Gordon only as her weight, Your Fat Friend spends time with Gordon’s parents as they talk about their daughter throughout her childhood and adulthood. The interactions between Gordon and her divorced parents sometimes feel awkward (many adult child/parent interactions do), but still tender; Finlay makes it clear that there is a great deal of love in those relationships. Yet, those relationships aren’t insulated from the anti-fat bias that circulates in the United States, and the documentary explores how both of Gordon’s parents’ concerns with their own weight and their daughter’s weight featured in Gordon’s childhood.

For many parents of fat children and adults who were fat as children and maybe are still fat, this dynamic will be familiar. I was taken to Weight Watchers for the first time at the age of seven, and I’ve written about the ways parents, especially mothers, feel pressured to “do something” about their children’s weight. I was touched by the tenderness with which the parents are portrayed. Finlay has chosen to portray them as deeply complicated and human and perhaps even regretful of how they approached Gordon’s weight as a child. In one scene, Gordon’s mother appears alone on camera talking about it being made clear to her that her daughter’s weight was her responsibility. After a pause, she says to the camera, looking both sad and pensive, that she worries her efforts sent a message to her daughter that she didn’t mean to send.

As Your Fat Friend’s narrative arc follows Gordon’s ascension to being a published author, her parents attend a reading at a bookstore featuring their daughter. The reading comes after she had been doxed online, an admittedly emotional and scary time for Gordon, but she summons her courage to do the in-person event. Up to that point in the documentary, Gordon’s parents and stepmother have seemed supportive but maybe not fully aware of all of her work, with her dad noting at one point that he should read more of her work. An airline pilot himself, he seemed to have only read one of her pieces, that about anti-fat bias and flying. At the reading, one of the more tender moments of the documentary occurs when he leans over to a stranger and whispers “that’s my daughter.”

Afterwards, both her parents see Gordon surrounded by people who want her to sign their books, but they also want to tell her how much her work means to them. Her parents give each other a gentle squeeze. It’s the first time viewers see them together in the documentary, and it seems to frame Gordon’s work as having the potential—by talking about what people often don’t talk about—to be restorative, a theme that is echoed as the film closes with Gordon swimming, looping back to a childhood activity shown at the opening of the documentary.

In Your Fat Friend Finlay has worked to present both Gordon and anti-fat bias as complicated, existing in constellations of relationships, power, and meaning. Much of what the documentary presents about anti-fat bias will not be new to people in Fat Activist or Fat Studies communities. Of course, that’s not really the point of the documentary. The point seems more to reach a general audience with that information and to let all of us see a nuanced depiction of a fat person in the world, a person with a daily life, aspirations, hurts, dreams, a family, complicated relationships, fears, and successes. As Gordon is working on her headshot for her book, she talks with the photographer about putting her face to the words in her book and the importance of that representation. I couldn’t help but think about the “headless fatty” again at that moment and all the ways that Gordon and Finlay resist the “headless fatty” in their work.