With the expansion of European empires from the late 17th century to the early 20th century, many indigenous peoples were oppressed by these foreign colonizers. Australia, just like numerous other colonies, went through harsh colonial beginnings with the Aboriginal peoples experiencing suffering at the hands of British colonizers. In Fred Schepisi’s film The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), the painful experiences of the aboriginals are showcased through the harsh treatments that the titular half–white, half–aboriginal character endures at the hands of the white Australian society. Through the various encounters of racism that Jimmie Blacksmith faces throughout the film and the numerous scenes of harsh violence, Schepisi is able to make one of the harshest critiques of Australia’s racist history.

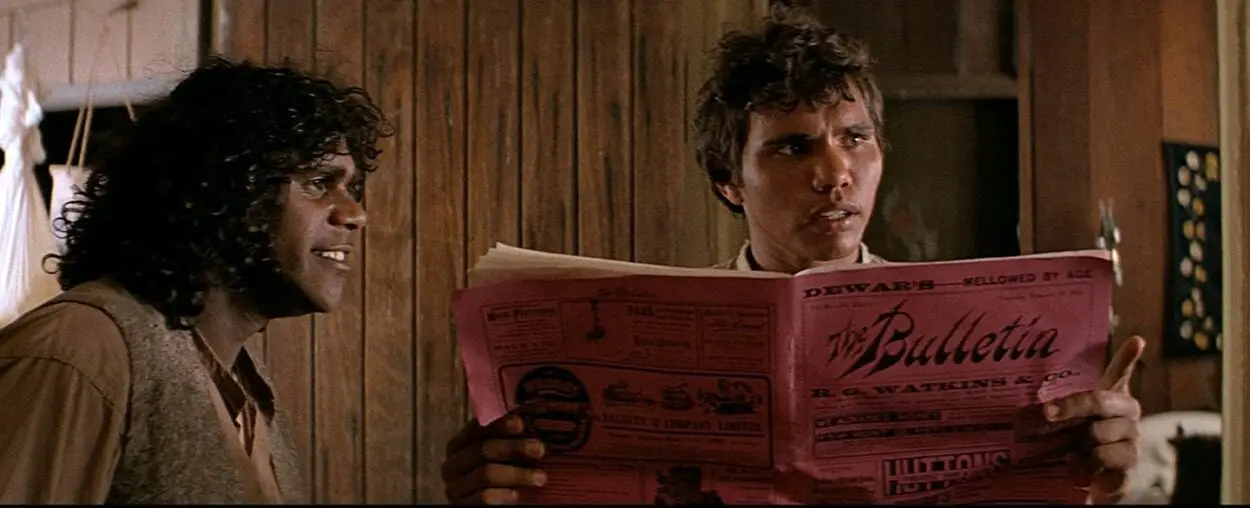

From the very beginning of the film, the division between Jimmie Blacksmith (Tommy Lewis) and the white Australians that surround him is established. In long shots through the window of a house, a white Reverend Neville (Jack Thompson) and his wife Martha (Julie Dawson) observe the child Jimmie Blacksmith. The first sentences from the observing white couple involve calling the young Jimmie harsh racial slurs as they decide to adopt him to take away any influence of his Aboriginal tribe to shape his future.

Even before the main story begins, the director is able to establish the racist environment that surrounds the main character, along with other Aboriginals, as the white characters signal disdain to their non–white neighbors through verbal cues of racial slurs, and by physical cues, distanced from the Aboriginals as the long–shots impart the noticeable separation. Furthermore, the white couple is shown to take in Jimmie not out of parental love for the young boy, but out of disdain for his Aboriginal culture as they want to make him civilized from a White culture’s perspective. As the film progresses and Jimmie grows to be an adult, he still encounters more examples of racial discrimination from the white settlers.

With Jimmie’s need for a steady job to support himself, he’s forced to partake in menial labor for various farmsteads, hammering in fences for the properties. These work scenes, shot in medium or close–up shots, underline the physically demanding nature of the jobs that Jimmie is forced to take, as his skin color doesn’t allow him to pursue any less physically demanding jobs due to the various racial discrimination from numerous employers. These work scenes are also shot in long takes to reinforce the grueling nature of the jobs as Jimmie works in sun–baked heat or torrential rain to gain basic wages, before being blamed for inadequate results despite Jimmie being shown as a hardworking individual, further showcasing the predatory nature of the white employers as they withhold payments on the excuse of stereotypically racial laziness.

Jimmie’s eventual marriage into a White family, based on the hopes of being able to integrate into Australian society, instead further isolates Jimmie from White society at large. The members of the Newby family, who employ Jimmie at their farm, belittle him for allowing his Uncle Tabidgi (Steve Dodd) and brother Mort (Freddy Reynolds) to stay with him on the farm, due to their Aboriginal ethnicity. From addressing the new arrivals with racial slurs and trying to convince Jimmie’s wife Gilda Marshall (Angela Punch McGregor) to leave him, the Newby family’s hatred of Jimmie and his Aboriginal relatives is just another example of the racial punishment that Jimmie faces throughout the film as they view Jimmie and his relatives as lesser people than themselves.

This division between the prosperous White family and the struggling Aboriginal family is underlined in the drastic living conditions that both families experience as the Newby family owns multiple rooms and large amounts of furniture, while Jimmie’s house is shown to be cramped and dirty, demonstrating the differences in the opportunity that both families have mainly due to their racial ethnicities. In addition, the drastic living styles show the imbalance of power between White and Native populations as Jimmie and his family depend on the Newby family to survive, while the Newby family lives comfortably on their farmland and can utilize cheap labor like Jimmie’s to gain all the benefits, while Jimmie is still left desperate and unsatisfied.

As Jimmie works in various locations and tries to start his own life away from his White adoptive family and Aboriginal relatives, the violent atmosphere of the film begins to reveal itself. When a white man is killed in self–defense by an Aboriginal man and Jimmie works for the local constable to hunt down and eventually capture the suspect, Schepisi focuses less on the violence of the murders, but instead on their results. With the limp body of the White man or the hanged body of the Aboriginal suspect in his jail cell, Schepisi makes these deaths effective as the reactions to the discovered bodies allow for audience shock at the severe results of these violent acts, just as the characters experience those same emotions.

The film–making also highlights the tragic nature of these violent ordeals as the close–up of Jimmie’s face as he disposes of the bloodied clothes of the Aboriginal prisoner, demonstrate his anguish and sadness, allowing for audience sympathy towards the traumatized main character. When Jimmie’s demands of proper payment for his work on the Newby farm are rebuked by his employers, Jimmie and Tabidgi take the drastic measures of scaring the White family with weapons before sudden bloodshed arrives, based on Newby’s family being scared to kill first.

With mostly static shots and longer takes, Schepisi makes this violent eruption much more disturbing in its showcase with Jimmie and Tabidgi’s axe swings on the begging and bleeding women do not cause immediate death, but is instead a slow and messy process, making the suffering of the women much more disheartening to witness. This shockingly violent moment also shifts the identity of Jimmie’s character as he shifts from an oppressed racial minority laborer to a revenge–seeking murderer that seeks to get justice for the misdeeds placed against him by White society.

As Jimmie and his wife flee from the farm after the carnage and he decides to leave her behind before escaping with his Aboriginal relatives, Jimmie declares war, both figuratively and literally, against White Australian society through various attacks around the country. These violent acts, just like the Newby massacre, are shown in brutal detail of close–up shots and unbroken takes as gunshot wounds lead to agonizing bleed–outs, making the world of the film realistic from an audience perspective; nobody falls limp from a single shot like in the gunfights of most movies, instead they writhe in pain to a slow and messy death.

Just as Jimmie and Mort act in brutal nature against the White society of Australia, the White society returns that brutality tenfold as each member is overwhelmed and paraded as hunting trophies like Mort’s death photograph with his killers, or Jimmie’s encounter with an angry mob and police escort after a severe facial wound from a gunshot.

The film ends in tragedy as Jimmie is captured and will be eventually led to his execution after the deaths of many people in the film. With Jimmie and Neville’s brief reunion in his cell before Jimmie’s inevitable death, the executioner looks through the cell door peephole to look at the two talking, before stepping away to prepare the noose. As the film began with a distant view of Jimmie through a transparent surface, the film ends on a different transparent surface before the lens closes, marking the end of the film, just as Jimmie’s life will now end. Even with Jimmie’s death, the cycle of abuse and retaliation killings will continue, just as it continues for those oppressed minorities in the still concerningly hateful modern world of today.