If you’ve never heard of nor seen Out of the Blue, a 1980 film written and directed by Dennis Hopper, you’re not alone. Hopper, hired at first only to act in the production, took over the reins from its fired director-writer, rewrote the script to put teen actress Linda Manz front-and-center, and delivered a knockout of a film. With a newfound focus on Manz’s character and her corrosive, explosive family dynamic, Out of the Blue would make for an especially sensitive portrayal of North American girlhood.

The only problem was that its producers would deem the resultant film simply too bleak for release. While Out of the Blue screened at Cannes and overseas, in Canada, where the film was produced, and the U.S., where Hopper and co-stars Ganz, Sharon Farrell, and Raymond Burr were all known entities, it went largely unseen for 40 years, save for a brief arthouse run in 1982. Working from the original 35mm negative, John Alan Simon and Elizabeth Karr’s Discovery Productions has since remastered and restored the film in 4k for theatrical release across North America in early 2022 and a subsequent blu-ray release.

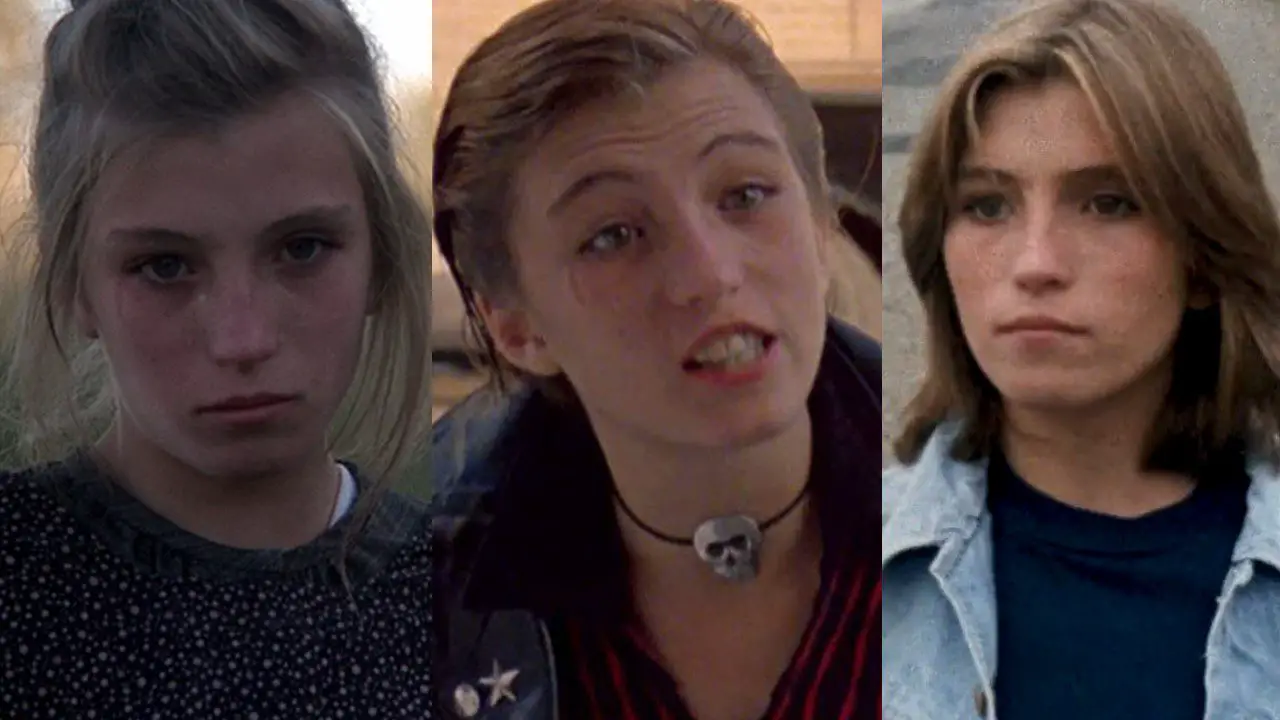

“Bleak” describes the film’s setting and events well, and viewers should be forewarned: Out of the Blue is no afternoon-special adolescent drama of triumph over adversity. In an era when most films about girlhood either reduced teen dilemmas to inconvenient trivialities or sexualized their young protagonists with makeover fantasies, Out of the Blue treats its subject with candor and respect. Onscreen for most of its 90-odd minutes, the young Manz—who made only a handful of films before a long hiatus—is terrific. Manz had been a magnetic screen presence as the younger sister and narrator of Terence Malick’s Days of Heaven and then as the androgynous Pee-Wee in The Wanderers before Out of the Blue. (Sadly, Manz died of cancer in 2020, as restorations on Out of the Blue were underway.) Hers is a unique persona too rarely seen onscreen.

In centering the film on Manz’s young “CeBe,” Hopper took an immense risk. Few films of the era (or since) treated the confusion and chaos of pubescence seriously. CeBe lives with her mother, Kathy (Sharon Farrell), a waitress, while waiting for her father, Don (Hopper) to be released from his five-year prison sentence. In a harrowing opening scene, Don drunkenly crashes—with CeBe in tow, dressed as a clown—his semi-trailer truck into a school bus. And a film that opens with the death of innocents will ultimately go downhill from there. If the crash happens out of the blue, the narrative will take the characters into the black.

Manz’s CeBe is caught in a maelstrom of turmoil. Her character worships Elvis as much as her dad, but the naiveté of the oldies she sings to her herself—especially “Teddy Bear”—betrays a dark, perverse secret about their relationship. Alternatively sucking her thumb and terrorizing her classmates, young CeBe is caught between childhood and adulthood, with no one to show her how to navigate her teens. Her father’s a drunken convict whose release offers no sign of remorse or redemption. Her mother’s an enabler with her own addictions. Adult men leer at young CeBe and the other girls, seeing them only as prospective sexual conquests. (Hopper’s deft touch as director is impressive as he silently charts a leering slug eyeing CeBe as the girls exit a cinema.) It’s no wonder she runs away.

But freedom and release are fleeting, and CeBe is on the verge of being trafficked before stumbling onto Vancouver’s burgeoning late-’70s punk scene. There, the briefly-great Pointed Sticks let CeBe handle the drumsticks, and for a time at least it seems perhaps she might have found a means of self-expression. In particular, punk’s anarchic, energetic, ‘f*ck-it-all-and-do-it-yourself’ ethos offered many young teens an outlet for rejecting their parents’ values and creating their own culture. But for all the rebel-without-a-cause exuberance the scene offers, none of it has any impact on the crumbling, decaying family she hopes to reunite.

Familial melodramas often chart threats to the nuclear family unit, whether those are external or internal. But in them, there is traditionally some presupposition that the unit itself is worth preserving. In Out of the Blue, the family unit—drunken Don, waffling Kathy, tormented CeBe—never really existed harmoniously, not even before the accident that sent Don to prison. And there’s no chance that after his release, they can be, as CeBe seems to desire so much, happily reunited. Don’s return is like lighting the fuse of a powderkeg.

Cinephiles must know what CeBe doesn’t: that a Dennis Hopper character simply won’t make for a father figure. Hopper’s anxieties, twitches, and stammers are on full display as Don, a man who needs to make amends for his past but who has no idea how to do so. Though CeBe clearly adores him—too much, it’s plain to see—Hopper’s other tormented, maniacal roles of the era in films like Mad Dog Morgan (1976), Tracks (1976), and The American Friend (1977), not to mention the later druggy photojournalist in Apocalypse Now (1979) or the creepy Frank in Blue Velvet (1986), aren’t far from his Don here. Just days out of prison, Don is quick to hit the booze and hatch schemes: his presence is like a tornadic vortex spinning out of control and pulling everyone else—CeBe included—in his wake.

Hopper was at the time of Out of the Blue reportedly in the throes of his own addictions. By the following year’s Human Highway he was reportedly snorting up to three grams of cocaine a day, according to Peter Biskind’s New Hollywood history Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—sometimes chased with a case of beer, a fistful of joints, and a pitcher of Cuba libres. Jimmy McDonough’s Neil Young biography Shakey recounts Hopper cutting one Human Highway co-star with his knife tricks on the set. Let me just say Hopper is wholly convincing and frightening as a user who cannot control his temper, addictions, or urges.

As a director, though, and even in the throes of his own addictions, Hopper’s eye is keen. Following the surprise success of 1969’s Easy Rider, he was given only one subsequent chance to direct: 1970’s abstract, commercial failure The Last Movie. Following that, and as a consequence of his on-set behavior through the ‘70s, no studio would consider putting him in charge of a set. But Out of the Blue demonstrates his talent, even under uniquely challenging circumstances.

The film’s use of the era’s music is especially acute. Hopper weaves together the lyrical content of his pal Neil Young’s “My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue)” from Rust Never Sleeps with its references to Elvis (“the king is gone but he’s not forgotten”) and punk (“This is the story of a Johnny Rotten / It’s better to burn out than it is to rust”) with CeBe’s plight in ways that are profoundly affecting and ultimately shocking. That in the years since the title song has gained even more gravitas, from Lennon’s reflections on it in his final Playboy interview and Kurt Cobain’s quoting it in his suicide note, lends its use an ethereal, elegiac quality.

Elsewhere throughout the film—whether CeBe is playing dress-up as Elvis or Don is thrashing his employer’s building—Hopper demonstrates a keen eye for the arresting visual image. And if like me, you lived through the late ’70s and bopped to punks, or even for that matter if you didn’t, you’ll appreciate the details of its mise-en-scène, from the denimwear and hairstyles to the Walkman cassette players and newly-emergent punk piercings, band buttons, moto jackets, and combat boots.

Today, films that depict young women’s struggles for self-actualization, especially in lower-income circumstances, are fortunately less rare than they were in the era of Out of the Blue. Though Out of the Blue’s protagonist CeBe is younger than any of these, the young women in the Molly Smith Metzler Netflix series Maid, Nicole Reigel’s Appalachian neo-noir Holler, or even Jessica Earnshaw’s marvelous documentary Jacinta (all released in 2021) all face similarly fractured family dynamics and dire economic straits. Alongside these and a number of other films, Out of the Blue, deemed too dark for its 1980 audiences, makes a certain kind of perfect sense to reconsider at the start of 2022, both as a look back at the punk era and to the kinds of stories that film has too often failed to tell in its past.

Out of the Blue is slated to screen at a number of independent and arthouse cinemas throughout the U.S. beginning in January 2022. It’s a treasure of North American independent cinema that is fully deserving of its remastering, restoration, and re-release. And it’s a visual treat to see the talented Manz onscreen again, even if that joy is tempered with the knowledge of her recent passing. Prospective viewers, though, should be forewarned that the film’s final act is deeply disturbing and may trigger trauma, especially for those who have experienced sexual assault or abuse.

For all its darkness, though, Out of the Blue is a film that aims for a truth that will explode the myth of the intact nuclear family. Deemed too bleak for release in 1980, today Hopper’s richly textured study of girlhood deserves to be seen—even if seeing it is itself a traumatic experience. Neil Young’s adage that “it’s better to burn out / than to fade away” is one Out of the Blue takes literally, and at its conclusion, as it takes us “into the black,” it makes clear that “there’s more to the picture / than meets the eye.”