Tokyo Drifter (Tokyo Nagaremono) is a film that both invites and defies categorization. An amped-up pastiche of spaghetti western and samurai melodrama tropes filmed in bright neon pop-art imagery, careening crazily between grimy waterfronts, stylish discotheques, and snowy landscapes, Seijun Suzuki’s 1966 yakuza borrows also from film noir’s most recognizable characteristics to create an early template for what would become known, decades later, as neon-noir.

Film noir, to take a brief step back, is one of those terms that beguiles film scholars—and has nearly since the French critic Nino Frank so dubbed a group of transatlantic films in 1946 that seemed to share a set of common characteristics. Was Frank describing a genre-in-the-making? Or were these films, delayed in distribution by WWII, less a genre defined by their narrative elements than a style, evolved from German Expressionism, or a movement, defined by a growing sense of fatalism inherited from West-Coast hardboiled fiction and its existentialist angst?

Regardless, over the ‘40s and ‘50s, dozens of films noir were produced each year in America (the peak being in 1950, according to three major references: Tuska’s 1984 Dark Cinema: Noir in Perspective; Silver & Ward’s 1993 Film Noir: Encyclopedic Reference; and Selby’s 1997 Dark City: Film Noir). And just as the initial movement seemed at the end of the 1950s, with Welles’s self-reflexive epitaph Touch of Evil, to conclude, the auteurs of the French Nouvelle Vague revitalized film noir with a new street-level attitude towards the B-movie crime film. By the mid-1960s, that influence spread across the world, sparking other “new waves” and including 1966’s Tokyo Drifter, Suzuki’s wild, weird, and wholly wacked-out yakuza that practically invented the notion of neon-noir.

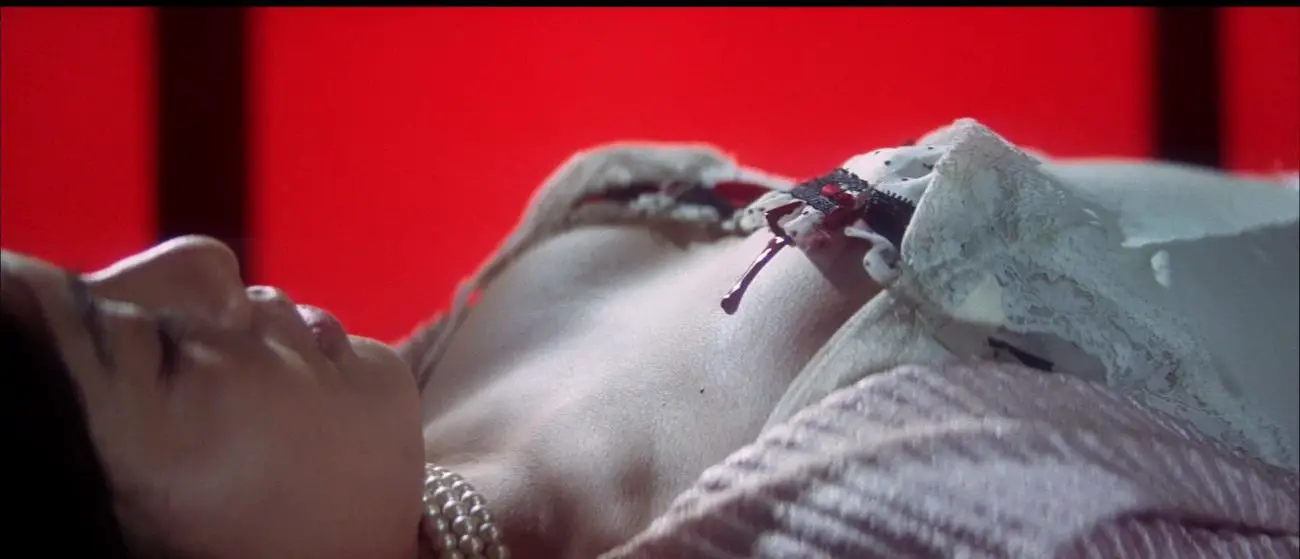

Neon-noir shares with classic film noir many narrative and visual tropes, from the urban settings and low-key, high-contrast black-and-white chiaroscuro to the labyrinthine, crime-motivated plots and the character archetypes of the detective, criminal, and femme fatale, all steeped in a brew of pessimistic fatalism. Neon-noir, a subgenre largely understood to have begun in the 1970s but still prominent today, updates the urban environment to the modern city with contemporaneous music and bold neon color and lighting for its visual scheme.

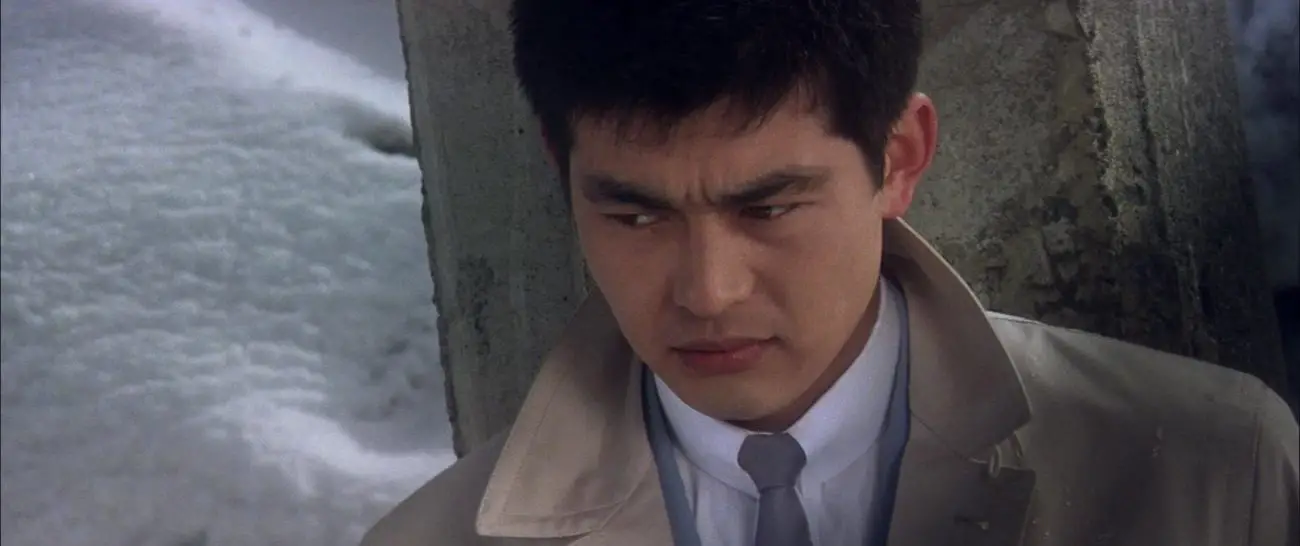

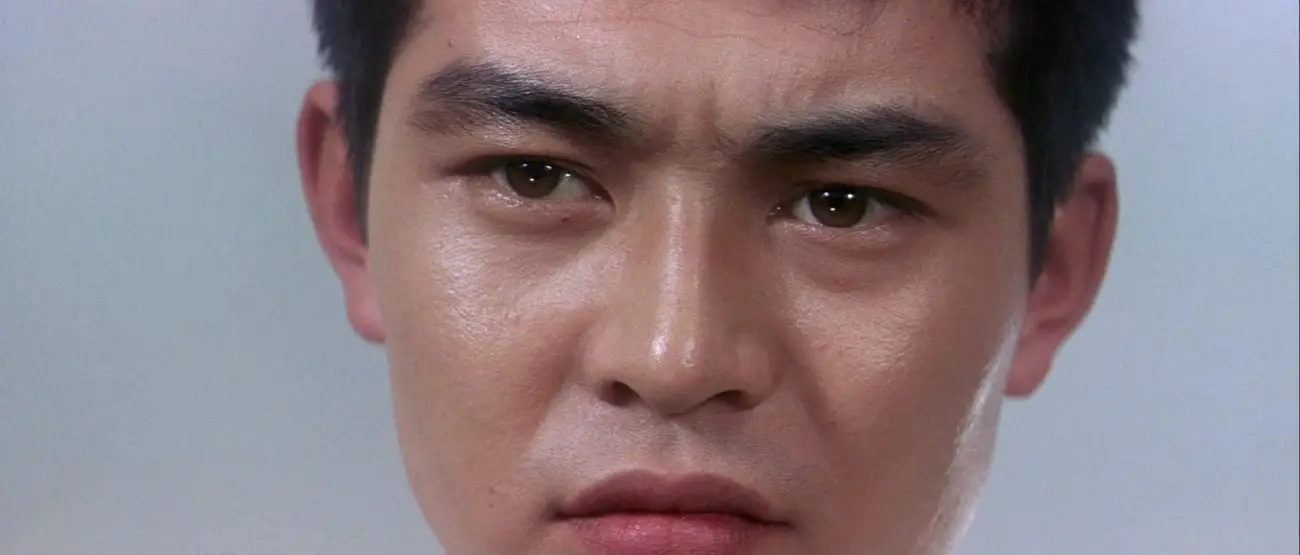

That definition neatly characterizes Tokyo Drifter, but Suzuki’s film careens all over the place in terms of its narrative influences, so a good place to begin might be with its plot—if plot matters at all to this film that is clearly more style than substance. Channeling Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars, the narrative is loosely about two rival crime mobs at war while a charismatic loner caught between them tries to go legit. That loner, the recently paroled and awesomely named ex-con Tetsu “The Phoenix” Hondo, the “Tokyo Drifter” of the title, is played by pop singer Tetsuya Watari.

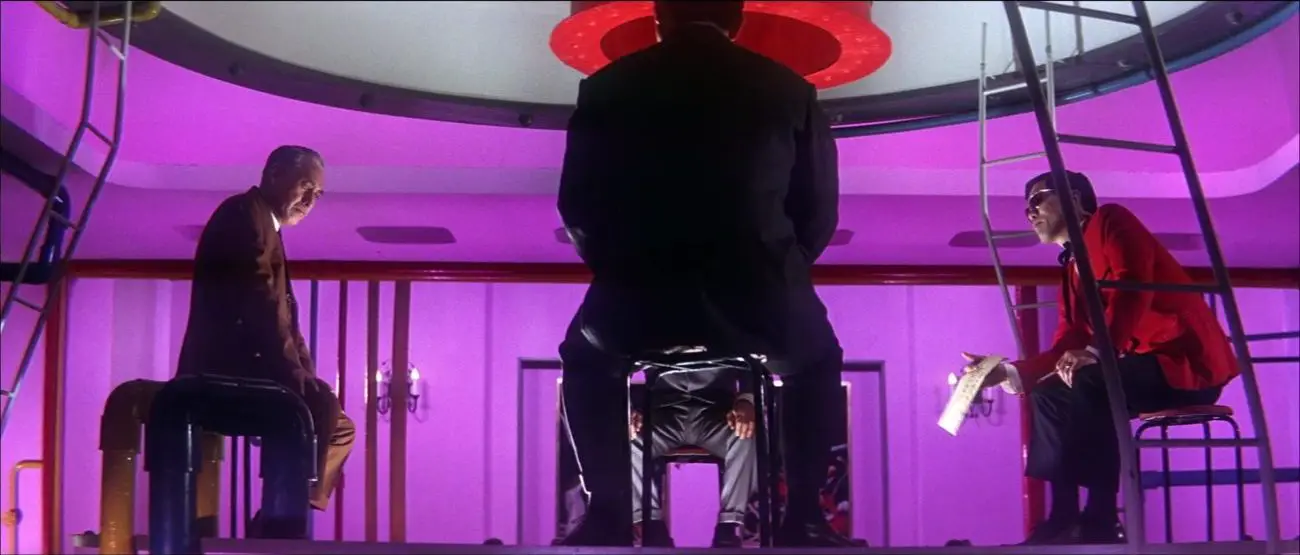

Tetsu’s boss is Kurata, a yakuza godfather gone straight and whose secretary, Mutsuko, cannot be trusted. Kurata’s ambitious rival Otsuko is a fast-rising, natty-dressing, sunglasses-wearing crimelord who keeps his headquarters in the back of a discotheque. Otsuko’s hitman—Tetsu’s chief rival and foil—is Tatsu, nicknamed “The Viper.” Otsuko and Tatsu pose a major threat to Tetsu and his nightclub-singer girlfriend, Chiharu.

Anyway, Tetsu takes the blame for a crime he didn’t commit and goes on the lam, followed by his rival Tatsu, the Viper, as he wanders the lonely landscape, sometimes whistling his own theme song. In the snowy north, he meets up with Umetani, an ally of his boss Kurata, and a lone-wolf type, Kenji, whose nickname is “Shooting Star.” There, Tetsu will have to evade his pursuers and face the challenge of the deadly Viper. And he will have to choose between his girlfriend and his “drifter” lifestyle. Zigzagging from Tokyo’s neon nightlife to snow-covered country vistas and a Wild-west-themed saloon, the plot had Suzuki’s studio bosses shaking their heads on first viewing.

This low-rent crime drama isn’t exactly what first comes to mind when one thinks of the Japanese cinema. “The Golden Age of Asian Cinema” of the 1950s was when filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa, with his rough-hewn samurai tragedies, and Yasujirō Ozu, with his gentle intergenerational dramas, first came to international prominence. These directors and their works gave the cinema of Japan a dignity of strength and nobility that would characterize its reputation in art houses and academia alike.

But the cinema of Japan existed long before Kurosawa and Ozu—and in many other genres and styles. Its history spans well over a century, and Japan’s today is one of the oldest and largest film industries in the world. It was in the 1960s that the number of Japanese films and filmgoers reached its apex, with most films shown in double features, the first half of the bill a “program picture” or B-movie. The 1960s also saw the influence of the French New Wave spreading internationally, including to Japan, including Nagisa Oshima’s Cruel Story of Youth (1960); Shōhei Imamura’s The Insect Woman (1963); and Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba (1964).

The Japanese New Wave filmmakers were not mere imitators of Truffaut and Godard. Though their movement began largely inside the studio system, they drew from some of the same international influences that inspired the French and developed into a critical and increasingly independent film movement of their own. The Japanese New Wave was less about a method than a general critique of convention, and Suzuki’s films—though most of them like Tokyo Drifter studio-fodder B-movies—did just that. And in time Suzuki would become a cult hero to generations of fans of genre cinema.

During his career at the low-budget Nikkatsu Studio in the 1960s, it hardly seemed Suzuki would be remembered at all. His first film there, like Tokyo Drifter a pop-song confection, earned him his contract and he delivered an average of three and a half films a year for his bosses there. His assignment entailed knocking out an array of different types of films at a breakneck pace, whether yakuzas, pop-song pics, Westerns, war movies, teen melodramas, or even softcore porn.

But over time, his increasingly idiosyncratic aesthetic choices got him put on a tight leash. After Tokyo Drifter’s brilliant follow-up, Branded to Kill (Koroshi No Rakuin), his 39th film for the studio, he was fired by Nikkatsu for, as he put it on his Criterion commentary track, “making films that don’t make any sense and don’t make any money.” To the studio, Suzuki’s films were increasingly incomprehensible; to his audiences and fans—and they are legion—that’s just part of the fun.

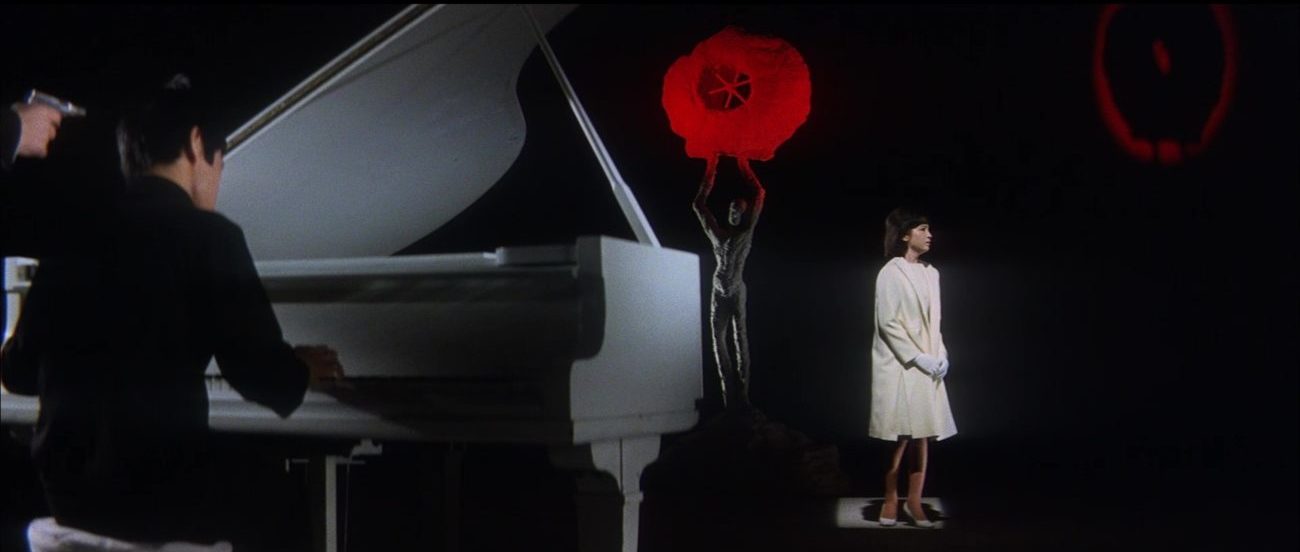

Tokyo Drifter’s extreme and self-conscious stylishness is a far cry from the static methodology of Ozu or the majestic swagger of Kurosawa. In fact, Suzuki stylizes Tokyo Drifter so much so that its narrative hardly matters at all: Tetsu’s quest is little more than an excuse to style his pop-singer interpreter in stylish duds and posit him in increasingly unlikely scenarios that seem to exist purely for the purpose of the visual. Suzuki’s set design borrows from 1960s pop-art and American Western films both to create something so revolutionary its influence would not be recognized for years: a neon-noir that creatively hybridized disparate influences into a form that was simultaneously old and new.

That he could make such a memorably stylish film is especially remarkable given that Nikkatsu provided Suzuki next to no money for sets. So, with clever lighting and crazy camera angles, the director turned blank space into striking images, just like a painter would with a blank canvas and pigments. He set showdowns in the snows of Northern Japan and in nightclubs that can’t possibly be nightclubs. His camera will peer down from the rafters or up through a glass floor, its locations creating unusual angles and impossible spaces. In a film where each narrative sequence occasions a new opportunity for visual invention, here are a few of Suzuki’s more memorable conceits.

That Suzuki could create such a brilliant neon-noir from such a rote assignment is something of a minor miracle in itself. Like it often did for its B-features, Nikkatsu would develop a script, basically, upon the basis of a hit song, and cast the singer in the lead. So here Suzuki was ordered to make the film as a vehicle for Tetsuya Watari, who Nikkatsu was grooming as a major star. But Watari had nearly no acting experience and was unable to deliver his lines whenever the camera was rolling—a case of stage fright without the stage.

Sujuki recalls in his Criterion commentary track how he sometimes stood to the side and poked Watari with a broom handle to get him to deliver his dialogue. Then Nikkatsu blamed Suzuki for Watari’s wooden performance: “You failed to promote Watari,” they said. But somehow, the pop star’s stilted delivery works perfectly for Suzuki’s stylized aesthetic. And Watari would go on to become one of Japan’s most popular stars, enjoying a long career as a singer and actor on stage and screen alike.

The result of a hastily-composed script from pop-song lyrics, a frugal budget, a draconian studio with an unyielding agenda, and bearing the influence of an international new wave of filmmaking, Tokyo Drifter is seen today as a tasty confection of surrealist pop art—even if, according to Suzuki, the director himself had no such aesthetic aspirations. In fact, his films were not especially well known outside of Japan until the home video revolution of the 1980s and the remastering and re-release of Tokyo Drifter, Branded to Kill, and others. Jim Jarmusch, Wong Kar-wai, and Quentin Tarantino all acknowledge Suzuki as a key influence, citing the inventive production design and intentional spontaneity of his films.

Tokyo Drifter in particular proved influential to the dozens of neon-noirs that would light up the cinema in decades to come: from the nighttime glow of The Driver (1978), the dark depravities of Hardcore (1979), and the harsh realities of Thief (1981) to the kitsch absurdity of Streets of Fire (1984), the hybrid tech-noir of Strange Days (1995), and the more contemporary neon aesthetics of Drive (2011) and Nightcrawler (2014), neon-noir has evolved into perhaps the most stylized, and stylistically recognizable, of all forms of noir.

Whether its pop-art surrealism was intentional or not, Tokyo Drifter meshed perfectly with the youthful 60s vibe, channeling James Bond, Spaghetti westerns, Andy Warhol, and dozens of other influences, both providing a stylish counterpoint to the magisterial dramas of Kurosawa and Ozu and profoundly influencing an entire generation of filmmakers. On the surface, its plot may seem incomprehensible, even irrelevant, but certainly Suzuki must have felt some affinity for a protagonist dedicated to his own unwavering ideology despite the pressure felt from external forces.

It may have nearly cost Suzuki his job—his next film, Branded to Kill, definitely did, if not overnight—but Tokyo Drifter employed the very essence of new-wave filmmaking to establish, for filmmakers and filmgoers for decades to come, a wholly new aesthetic that transformed traditional film noir tropes and techniques into the brightly lit, highly stylized, and immediately recognizable contemporary idiom of neon-noir.