It is the dreaded (but very clean) year 2018. The world is run by corporations and all is organized and prioritized according to business models and efficiency reports. Male human assets are assigned women when the company sees it as beneficial to public perception and in said male’s best interest. Television is state-run and there is only one event that matters to the people of the entire, united world: the bloody Rollerball league.

Rollerball is yet another ’70s science fiction dystopian film that manages to predict, almost to the date, the value of bloodsport and corporatism in entertainment in the United States. But unlike other dystopias we’ve looked at in the previous entries of this column, Rollerball is shown from the shinier, cleaner side of metaphor: the perceived utopia. For the world of Rollerball is one of pristine towers, lovely gardens, and streets that haven’t seen a drop of blood in ages.

But it all seems a bit too perfect. So inoculated to the machinations of corporate governance are the people that violence has become one of two things: either a hysterical pastime worth giggling over and/or the sport of choice on TV with Rollerball matches. In one scene, a rich man at a party shows off his antique gun. Most stare in wonder, marveling at the alien nature of the item, and later go out into the backyard and shoot some trees, obliterating them into balls of fire, reveling at the destructive power of such a small object. First-hand violence is certainly a thing of the past for the population, but this scene reminds us that it is something that keeps the people’s interest when seen from the outside looking in and unable to feel its effects.

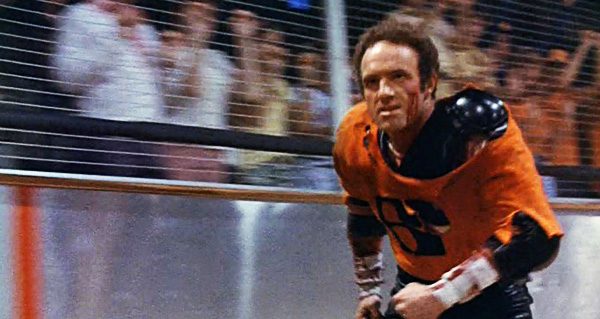

Nothing speaks more to this than the USA’s obsession (though it is implied that it is worldwide) with the fictional Rollerball, a sport where men can assault each other in order to score points (their uniforms include spiked gloves and live motorcycles). The rules are barbaric enough as is (in brief, in order to score points, one must go through rollerskating marauders and motorcycled goons that protect a tiny hole where the titular rollerball goes) but when the corporations decide to take out penalties, which previously curbed players’ intentions to literally maul their opponents, literal lives are on the line.

The players of Rollerball are mostly anonymous cannon fodder, but Jonathan E (James Caan) has become a superstar for the Houston team. He is revered worldwide and Energy Corporation Chairman Bartholomew (John Houseman) not only wants Jonathan to retire but to go out with a worldwide reality show depicting his final days in the league. For the corporations, any sign of cult of personality that is not them is to be smashed and since Jonathan won’t retire… and is too good to be killed under the traditional rules… They’ll keep upping the ante on Rollerball until all signs of individuality are erased.

Rollerball’s explosive climax is not only an adrenaline-packed thirty minutes of rollerskating mayhem but is also the perfect metaphor for corporate cynicism vs individuality. Though Rollerball sputters in its quieter moments, the film’s three exciting Rollerball sequences provide thrills as well as something worth talking about. In a time before Carter’s “malaise” speech and the self-indulgent economy of the 1980s, there was fear of the future. Rollerball is those fears made flesh. And also, shockingly, mostly made true.

It is the dreaded… well, more spoiled… year 1983. Any pleasurable whim man can conjure in their minds can be purchased for the right price. Got a few grand to spend? Go to one of the highly specialized theme worlds provided by the Delos corporation. Fancy a joust and a roll in the hay with a lecherous queen? Go to Medieval World, where knights and vassals serve you drumsticks of turkey while you plan your next sexual conquest.

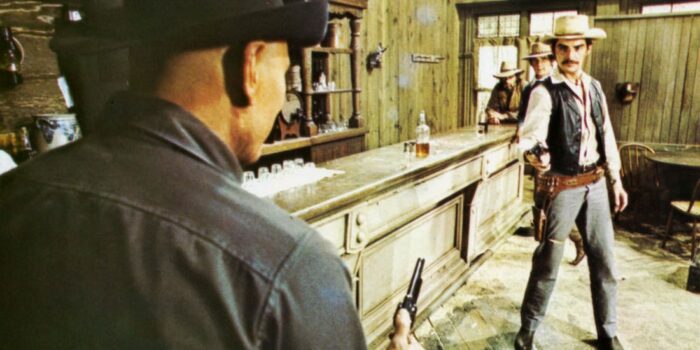

Perhaps too Renaissance Faire for you? You can always engage in a Senate debate, complete with toga and grape-serving pleasure maids, in Roman World where political machinations and sexual intrigue take precedence over historical accuracy. Far too civilized? Of course, if you are really looking to rough it, hitch over to the nearest Brothel/Inn in West World on your best steed and face off with the best sharpshooters in the world. I’m sure you don’t mind shooting robots but are you okay with sleeping with them? Of course you are.

Westworld (1973) is an exciting sci-fi/fantasy film that takes a look at a more ethically bankrupt world, a moral dystopia, where the upper crust of society can escape to literal fantasy worlds and indulge themselves in untoward pleasures denied them in reality. Man’s inherent quest for bloodshed and sex is a simmering reality in this film where those desires can be acted out on unfeeling, unknowing robots.

And while there is a metaphor for man’s baser nature on the overt surface of Westworld, the more subtle allusions are to class warfare. The robots are basically servants and they continually get shot or screwed to literal death. Westworld‘s big twist is when the robots’ restraints come off and they start to really kill those that threaten them. It becomes a bloody Upstairs/Downstairs with androids and it is a really good time.

Almost intentionally, the “heroes” of our story are mostly undersized, fairly attractive men (though my mother would argue that James Brolin is a “hunka hunka burning love,” whatever the hell that means). They seem like the type that were blessed with being rich but used to being pushed around or emasculated. For the first hour of the film these men are fighting with physical specimens like Yul Brynner (and winning) and having sex with buxom, but braindead, hotties who require nothing of the man but their presence.

And though Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin), the audience avatar, is likable enough, his depiction comes off as slightly skeevy. His buddy John Blane (James Brolin) doesn’t come off as much better. They just appear to be too pseudo-lecherous guys looking to blow off steam. They are only our heroes because the story demands it, but there is a sick sense of satisfaction when Peter and John, among other like-minded guests, are sought for destruction by the very robots they were abusing.

The final thirty minutes of the film becomes a grand chase as Brynner’s character, now able to fulfill his true identity as The Gunslinger without limitations, hunts down Peter. His internal operations were always to kill and the blocks in his programming always led to his death. Now he has control of his destiny and the smarter, faster, stronger Brynner is taking no guff from Peter. And does the good guy win? I suppose that’s up to you on determining who the good guy really is.

Westworld did have a sequel (Futureworld, which I haven’t seen) as well as a successful television series on HBO (which I also haven’t seen). But based on the praise I’ve heard for the latter, it appears Westworld‘s broad themes of violence and class systems are expanded upon. And that can only be a good thing. But if you are looking for a little social commentary in your rock ’em sock ’em robot sci-fi film, look no further than 1973’s original Westworld.

Both Rollerball and Westworld are available as part of the “‘’70s Sci-Fi” collection on the Criterion Channel. Also available wherever digital or physical media is sold/rented.