What makes us human beings? I ask myself this on a daily basis, especially more lately in the environment we have created. If we go by Merriam-Webster’s definition, human means “1: of, relating to, or characteristic of humans”; but they also define human as “representative of or susceptible to the sympathies and frailties of human nature”. This struck me as the one definition coursing through the veins of the 1999 movie Bicentennial Man. What people once took as a light-hearted Chris Columbus directed drama (and also a group of two stories by Issac Asimov which the movie is based); I took as a definition of the human condition and what sets apart man from machine. What truly makes us ‘human’?

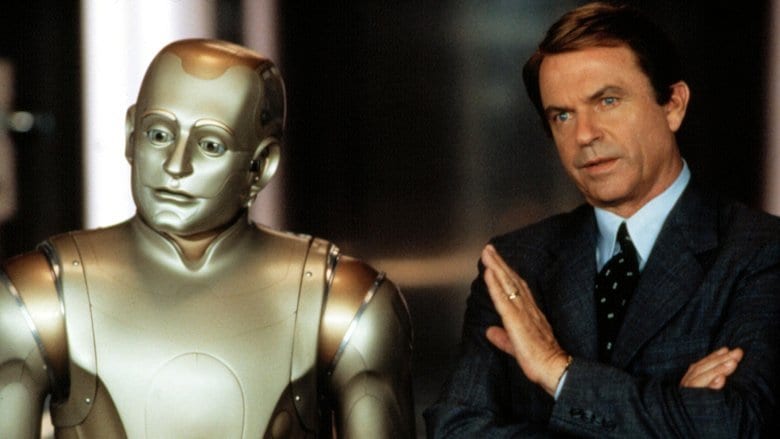

In the year 2005, we are introduced to Andrew; an NDR robot tasked with completing everyday chores that humans are too busy to perform for themselves. Think of these robots like Rosie in The Jetsons: cooking, cleaning, maintenance, and pretty much anything else that is needed to keep everything spic and span and organized. Andrew is played beautifully by Robin Williams.

Let me stop and take a moment to gush about the performance that Robin Williams gives in this movie. This was not a critically acclaimed movie by any means, but what Robin gives to this part makes me cry every time I watch it. Robin Williams understood the human condition better than most. He could make you laugh, make you cry, make you cry laughing; he could make you feel every human emotion with his performances. What he does in this part is make you believe that being human is more than just being born a flesh and blood human being, but recognizing every emotion and feeling of humanity is what being a human is.

Andrew’s matriculation into the Martin family is a little bumpy at first, but during a particularly harsh hazing by the oldest Martin sibling, Grace, the family and especially ‘Sir’ Richard Martin discover Andrew can read emotions and return those emotions in kind. Not the kind of thing you would expect from a machine programmed to just be obedient. Andrew forms a special relationship with the Martin family’s youngest daughter, who he deems Little Miss. In one particularly tender moment, Andrew breaks Little Miss’ horse figurine and feels terrible, so he makes her another by carving one out of wood. When Sir inquires to the manufacturer, the company sees this as a flaw in Andrew’s programming and offers to dispose of Andrew and issue a new robot to the family.

Is this what we do? When someone shows us care, compassion and humanity, why as a society do we wish to kill or cull these emotions and feelings of others? Do we feel we are too far gone with our ‘programming’ to change the way we feel about things? The way we feel about life and about living that authentic life?

Years pass, and once Little Miss gets married and leaves the family home, Andrew realizes his time with the family is coming to a close. Wanting to explore and be free to choose his path, he asks Sir for his freedom, but Sir goes one more and banishes Andrew so he can be completely and utterly free. This part killed me a little bit because I feel part of the human condition that we have been lacking as of late and what makes us thrive as human beings is a connection. Having the connection to another, to a family, the connections to our humanity as a whole group of individuals, all of these a part of that condition. Freedom of self is important, but when trying to find your way, remembering where you came from is a very important step. It’s that very important step that ‘Sir’ Martin remembers when Andrew visits him on his deathbed. Sir apologizes to Andrew and finally realizes his regret in his decision to banish Andrew. Andrew was more than just a robot; he was family. Andrew senses this regret but puts Sir’s mind at ease when he states a final time “One is glad to be of service”. Cue the waterworks.

This brings me to another step toward man vs machine: service. We as humans thrive on what we can bring to others. Whether that is making someone laugh, bringing them comfort in a time of need, assisting someone when they need help; but being of true service to the human condition is helping one another no matter the cost. A machine is just of service through programming. It serves you as you wish, not because it thinks of service as being more than just cleaning up a spill or doing your laundry. Andrew starts off just being of such service but ends up being so much more, a very integral part of the family and its dynamic until his time was finished. He very much was still a machine taking orders but knew his service was no longer needed in the way it was originally meant to exist. Does being human mean recognizing and adapting to your environment in new ways when your service is no longer needed or required? Recognizing the differences in what that makes you?

It is then that Andrew goes onto try to locate as many NDR robots as he can to see if they are ‘like’ him. He does locate a female NDR by the name of Galatea, whose owner, Rupert Burns, is the son of the original designer of the NDR robot. With his help, Andrew starts his journey towards looking as human as he feels. This part always makes me laugh; because I think as human beings, we take for granted emoting how we feel. As children, we constantly laugh, smile, cry, pout, and do so in grand mannerisms. Once you grow and get older, we are taught to hide how we feel or to “be strong. “Don’t cry!” “Stop laughing!” So we tend to forget what it is like to feel your cheeks curl up into a wide grin, or feeling your mouth tighten as you scowl during a disagreement. Is this one more way to show our humanity? I do believe so. Your face tells a story, and if you have no way of showing those emotions outward, how do you portray what you are feeling to another, especially in the ways of love and death?

Andrew ends up meeting Little Miss’s granddaughter Portia, who miraculously, through a recessive gene, looks exactly like Little Miss. Portia becomes someone that Andrew grows extremely fond of. He begins to develop feelings of care, then of affection, and soon realizes love; not only love but sexual love as well. Portia put this in perspective as well: “What’s right for most people in most situations isn’t right for everyone in every situation! Real morality lies in following one’s own heart”. But remember, Andrew essentially is a machine. Little by little with Rupert’s help, he is replacing systems within his construct with ‘human’ systems: a central nervous system, a beating heart, the senses of touch and taste. But does this make him a machine with human parts or human? In one of the best explanations I have ever heard about the human connection we have with someone we love during the act of sex, this is quite perfect.

Andrew: “That you can lose yourself. Everything. All boundaries. All time. That two bodies can become so mixed up, that you don’t know who’s who or what’s what. And just when the sweet confusion is so intense, you think you’re gonna die… you kind of do. Leaving you alone in your separate body, but the one you love is still there. That’s a miracle. You can go to heaven and come back alive. You can go back anytime you want with the one you love.”

One of the last and largest ways Bicentennial Man sets apart man and machine is through the idea of death. First with Sir’s death, then with Little Miss’s death. Andrew realizes that everyone around him that he ever cares for will one day die. It is only when he becomes involved with Portia that he knows he needs to be recognized as a human being for them to be recognized as a couple and to live their lives out together, but he cannot achieve the one trait that truly makes you human: death.

Machines cannot die. They can cease working, be decommissioned, and left for ‘dead’, but they cannot die. Machines, as long as they can be upgraded and fixed, can be ‘immortal’. When realizing that someday Portia will die just like everyone else he has ever cared about, Andrew has Rupert (now an old man himself) introduce blood into his many ‘upgraded’ systems. This addition truly brings Andrew one step closer to being a true human. Since he does not know what the blood will do to his systems, he will not know when he will die, but he knows he will most assuredly die at some point.

In one of the most poignant parts in the whole film—I am tearing up just writing about it—Andrew petitions the World Congress one final time about declaring him a human being. Now appearing in front of the Congress old and fragile, his one final plea got me: “As a robot, I could have lived forever. But I tell you all today I would rather die a man…than live for all eternity as a machine.” We soon see that Andrew is indeed going through the final of human conditions as he is on his death bed listening to World Congress finally designate him as the oldest living human being aside from “Methuselah”. They also recognize his marriage and love of Portia. When Portia, also on her death bed, looks over at Andrew, she realizes that he has died and we are left not knowing whether he heard the decision on his humanity. So Portia orders her ‘nurse’, the now more human herself Galatea, to unplug her so she can die hand in hand with her husband. As a callback, of course, the penultimate line is Galatea saying, “One is glad to be of service.”

Where does one stand on what it means to be human? Is it giving service and guidance to one another? Is it the functions of the body that make us age and eventually die at a time not of our knowing? If machines are given all the systems and emotions that humans possess, does that make them human or just an upgraded immortal machine? Bicentennial Man makes you ask all these questions of yourself. I do know that the human condition is one in which I feel blessed to be able to continue in, but I am also starting to see the cracks. Essentially, at the core though, all we want is to be acknowledged in our lives; that we lived and lived well by the standards we set for ourselves. To feel and live and love, as we wish, on our terms as human beings, seems like a simple task, possibly one each and every one of us takes for granted every day. Remind yourself to feel your humanity every day, because one day we may wake up and realize that what makes us human mattered more than we thought was ever humanly possible.

This film was a bad retelling of the Bicentenial Man novel and the original short story. If I divorce myself from how much more I like those, though, it was actually not an awful film and William’s portrayal of Andrew Martin is (as you would expect) heartfelt, touching, funny and tragic. My wife tagged along to the movie on the strength of Robin William’s being brilliant, and she loved it so much she read the book I’d raved about for years. She hated the book, because it didn’t have all the “girl stuff” the film stuck in for (lets face it) the partners of sad Sci-fi nerds who went to watch it because they were excited to see ANYTHING Asimov on film.

The 3 laws Andrew must follow, set him apart from the human characters, make him “less then” in the film, but the point is that in following the 3 laws, he behaves more humaly and humanely than the humans in the film (tin-man’s treatment by humans in the book is, if anything, more brutal).

For a more drawn out and thoughtful rendering of Bicentennial Man, see the inversely titled series Humans, form the UK or Real Humans from Sweden (on which the excellent brit series is based).

Stumbled over this and I thought I would comment, hope you see it. The problem with Bicentennial Man is that the moviemakers were looking for max revenue so they did not deal with one of the fundamental questions of death – do you “live on” in some manner or do you just disappear into the void? Otherwise known as the “Heaven” question.

An Artificial Intelligence like Andrew is effectively immortal (until the heat death of the Universe at any rate) so it does not “need to go to Heaven” No matter how much it grows and learns no matter how smart it becomes it always exists in what we know as “the real world” It doesn’t have to worry about what happens to it after it dies because it doesn’t die. It probably would not want to love and become emotionally involved because it would repeatedly see people it loves grow old and it would suffer the pain of seeing them die.

However, an AI that “dies” after a finite amount of time is subject to the same “tragedy of the human condition” which is that us humans have a far shorter lifespan than what is needed to learn everything there is to learn. We die still learning. Such an AI might want to reproduce and create children to live on beyond it’s own life. It might want to create things that would live on after it dies. It might want to know if there is a Heaven and if it would go there and see once again all it’s old friends and it’s loves.

I think the moviemakers didn’t introduce the “Heaven” question even though it is such a fundamental part of wanting to choose to die most likely because they knew if they brought in even a wisp of religion that many people would think “Oh it’s just another preachy religious movie” and not go.

So the end result is the move falls short of truly grappling with the AI question. Even Issac Asimov who was a vehement Humanist all his life and continually asserted that an Afterlife is a moot question, eventually at the end of his life weakened on the Heaven question and said “And when both die — I almost believe, rationalist though I am — that somewhere it remains, indestructible and eternal, enriching all of the universe by the mere fact that once it existed”

The question really isn’t whether a computer such as the one in Andrew can be programmed to be “intelligent” or “self aware” I think eventually it can be. The question is whether an AI would ever ask “Why am I here?’ ‘What was I meant to be?’ ‘Is this all that I am? Is there nothing more?

In Bicentennial Man, Andrew never asked that. Issac Asimov claimed throughout his life that he never asked that either. Although at the end – he DID ask that.

When we have a machine asking that – then we will have developed a real AI. Until then – it’s just a machine.