To be a horror fan is to become fluent in a new language of sounds. The twist of celery becomes bones-snapping. Wet crunches of bitten apples become zombie teeth in a screaming survivor’s shoulder. Any strange noise could be the solemn mating call of a dark plot soon to hatch.

Our ears become attuned to these noises: creaks, hooting owls, and screams. They become a second shared language. Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981) is, to me, the finest and most poignant of the director’s many cinematic love letters to Alfred Hitchcock.

With unimpeachable pacing, clever characters, and a deep, twisting, detective story at its core, the film becomes a heartfelt story. It becomes about two people finding each other as their worlds crumble around them. The film’s script gives a slick modern twist on Rear Window (1954) and De Palma’s loving lens turns John Travolta into a streetwise Jimmy Stewart and Nancy Allen into a jean-jacketed Grace Kelly.

Overheard and Overwhelmed

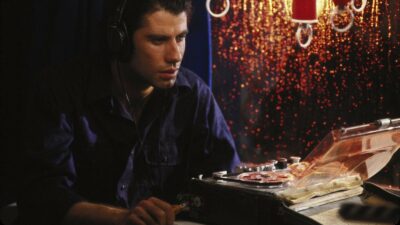

Blow Out is the story of Jack (played by John Travolta), a sound designer and foley artist for low budget horror films. After a test screening of a new sorority house slasher, Jack must find two new sounds: wind and a scream. Near a river later that night, armed with his shotgun mic and recorder, Jack accidentally records a car crash that kills a presidential candidate. Inside the car with the candidate is Sally (played by Nancy Allen), a call girl. Jack manages to save Sally and the two leave the hospital and enter a labyrinth of risk, secrets, lies, and murder.

Relief pitching the sumptuous two-hander of Travolta and Allen is John Lithgow’s crazed performance as Burke, a contract killer. When Sally survives, Burke takes the initiative to kill her with an ice pick. Naturally, he kills the wrong girl. Even more naturally, he decides to murder a sequence of Sally-lookalike prostitutes to mask the political killing. The phone call to his boss where he explains the decision is one of the best phone calls in cinema history. Bar none.

One of Us

Blow Out opens with a by-the-numbers voyeur slasher sequence. Then it playfully pulls out into Jack and his boss watching their work. This is De Palma telling us, these are our people. We’ve all been the horror fan watching idiots run upstairs or drop their keys or say “Who’s there?” into the dark. Blow Out gives us a protagonist with that language on their tongue. At no point in the film do we feel like Jack is behind us. By watching a horror film, we mistrust every character Jack encounters (except for Sally, because it’s impossible not to trust Nancy Allen). Jack, by virtue of his life in horror, expresses that same mistrust.

De Palma brings all of his talents to bear on this film. And, with one of his biggest budgets to date, it’s quite a few talents. De Palma essentially goes nuts in the best way. His trademark split-screen makes an appearance alongside fetishistic Touch of Evil tracking shots. Most impressively, De Palma teaches us about the magic of filmmaking itself in a sequence where Jack syncs his recording of the candidate’s car accident with leaked photos of the accident. In this movie about our merry tribe of movie lovers, De Palma brings down Promethean fire of how our worlds are made.

In Nancy Allen’s Sally, though, we get a departure from traditional genre storytelling. Despite being a call girl, Sally moves through the world of Blow Out with a street instinct learned only from the inside. She smiles and giggles and trusts perhaps too easily, but Sally is nobody’s fool. She allows herself to be played and cajoled because that’s a language she’s familiar with. She’s one of the defining performances in a genre full of compelling performances from women.

Sound and Spectacle

Blow Out plays host to a parade of astonishing visual set pieces and shot compositions that stand out amongst a filmography full of standout sequences. The film’s ending, amidst a swirl of fireworks and a parade, still causes me to tremble even at this writing. Brilliance shines under a layer of New York sleaze and pulp propulsion.

De Palma’s interest in Hitchcockian narrative echoes in every line of dialogue as John Travolta’s Jack speaks with the same steely certainty and inquisitive fear as Jimmy Stewart’s Jeff in Rear Window. A creative’s obsession and struggle with perception flicker with the same life as Michaelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966). Even in a plot as suspenseful and caloric as Blow Out’s, De Palma finds a way to bow to the Virgils that led him to his powers as a filmmaker.

Despite a career that spans genres and speaks to an eclectic creative mind, De Palma speaks our language. He speaks the language of horror lovers, and we know this because of Blow Out. With all of its sleaze, cinematic in-joking, and suspense, this is a movie that, for anyone not so deeply in the know, might as well need subtitles.