On October 8th, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark report to relatively substantial media coverage—a report that has everything to do with science and the future, rather than our latest political disaster. This coverage lasted a day, if that, before we collectively sighed our despair and moved on. The report itself is urgent, and fascinating, and terrifying. I don’t believe we have the political will or the ability to even care enough to do anything about it, and I fully expect to be living in a drought-blighted wasteland before my eventual retirement, probably at the age of 80.

But I digress. The reason I am bringing up this report is the collective lack of care that we feel, collectively, towards our impact on the environment. The scale of the problem is almost impossible to process for our brains, resulting in us seeking small, incremental changes at best, when what we really need to save the planet is impossibly huge, and will require sacrifice, hard work, and commitment. As humans, we struggle to process the importance of abstract thoughts. Our brains are hardwired to seek connections and patterns, to be sure, but that doesn’t mean we’re capable of acting to prevent a pattern from occurring in the first place, and that’s what we need to do. Instead, climate change and our impending environmental disaster feels far away—something that will only affect us generations down the line, rather than something that is happening right now, in this moment.

The Anthropocene is a word coined and proposed by academics in 1999 to describe our current geological epoch, starting from the successful test of the atom bomb in the 1950s. The idea is that humanity’s impact on the environment is so great that we will leave marks on the strata of the Earth. No other species can make a claim to this phenomenon—to have literally changed the structure of the world through our own actions. Our way of thinking about climate change is a fallacy. It isn’t something abstract for the future, because it’s something that’s already started. We are undergoing these changes along with our planet and we are struggling to care.

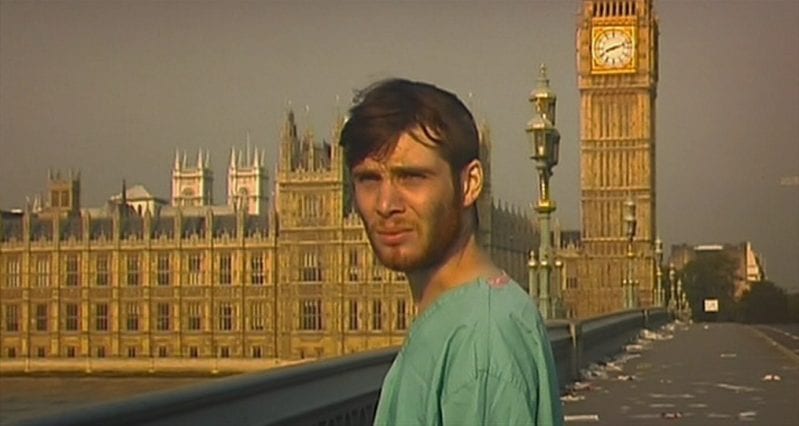

Which brings me to 28 Days Later (2002), oddly enough. It was the first collaboration between director Danny Boyle and Alex Garland, who wrote the screenplay, and it is entirely focussed on the impact of sudden, radical, traumatic change on society. In the film, Jim (Cillian Murphy) wakes up from a 28-day coma to find that Britain has collapsed into a zombie-infested state. To be fair, the film doesn’t refer to them as ‘zombies’, perhaps that’s too corny for a dark and gritty film from the early 2000s. Instead, they are infected with a rage virus, unleashed by well-meaning, but ultimately clueless and short-sighted environmental activists, ironically enough. The zombie story unfolds along the ‘typical’ lines—Jim bands together with a small group of fellow survivors, and they quickly learn that above all else, the true monster is actually man.

That’s less interesting to me than the exquisite sequence of scenes where Jim wakes up from his coma and makes his way through the streets of London, utterly and disturbingly alone. It’s London devoid of crowds and noise and chaos—in other words, it doesn’t feel like London at all. Essentially overnight, Jim’s entire life has been upended. It’s the rendering of the familiar into the uncanny that disturbs the most. He walks over Westminster Bridge, shouting for anyone to answer him, but of course, there’s no-one around. This sequence seeps into you—the quietness being so incongruous as you wait for it to break. It’s a relief when the zombies appear, a break in the tension.

It reminds me of another neologism, this time coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht in 2003—Solastalgia. It refers to the impact of environmental, industrial, or political damage that renders a previously familiar landscape unrecognisable. “Solastalgia speaks of a modern uncanny […] the home suddenly become unhomely around its inhabitants”, wrote Robert Macfarlane in an article for The Guardian in 2016. The landscape longed for by the ‘solastalgic’ person is irretrievable, lost forever to what is, primarily, human arrogance and greed. The tragedy of 28 Days Later is how completely society is upended. No-one would ever be able to return to how the world was before the rage virus was unleashed, and all that remains is to become used to this new, suddenly imposed, world order.

This is how climate change will appear in hindsight. For now, it feels slow. Our planet on a slow crawl towards disaster, but what is lost through damage to the environment will feel, in our experience, like it happened suddenly, as though we woke up one day to find Florida reclaimed by the swamp, or the Maldives completely submerged by rising ocean levels.

Annihilation opens similarly to 28 Days Later. Lena (Natalie Portman) is suddenly confronted with something that completely upends her life in the space of a moment—the return of her husband, Kane (Oscar Isaac). From the flashbacks later in the film, the viewer gets the impression that Kane has changed completely. Whereas he was comfortable and lively before his disappearance, joking with his wife and enjoying a quiet day with her, following his reappearance, Kane is disconcertingly silent. He is reluctant (or unable) to speak of his experiences in Area X, and can barely get out more than monosyllabic responses to Lena’s questions about where he had been. “I think I’m owed an explanation”, she tells him with her arms crossed defensively over her chest. He stares at his hands and his glass of water instead of responding. Of course, however much she might want an explanation, she is owed nothing. Just as the audience isn’t owed answers for what they see with her in Area X, Lena isn’t owed easy answers. She has to live with the abruptness of the change wrought upon her husband just as much as we have to live with the mystery of the very alien presence in the lighthouse.

The novel of Annihilation, by Jeff VanderMeer, was inspired by Florida and, more specifically, its swamplands. Florida is unique in that, more than most regions of the world, it has been utterly transformed into somewhere habitable. This happened in the latter half of the 20th century, as its population exploded due to a confluence of factors including immigration, the draining of the Everglades and, of course, Walt Disney World transforming the northern part of the state into a hub of tourism and commercialism. Florida is a product of the Anthropocene, and VanderMeer understood that. Its seemingly sudden transformation is a product of human ingenuity and greed, but it won’t last forever. One day, sooner than you’d hope, the Everglades will reclaim its lost land, and the ocean levels will claim Miami, rendering the state unrecognisable to its current inhabitants.

But the wreckage of humanity will still litter that landscape. It’s not something that we can ever take back, even if we wanted to do so, and that’s something that Garland understands. One of the most haunting images of Annihilation was, for me at least, the exploded body of a former explorer of Area X. It was skeletal and turned inside out, and out of it grew flowers and plants in a gruesome mockery of a mural. It’s a beautiful image and a perfect metaphor for what will happen as we march further down our current environmental path. It is the literal use of humanity as a frame for the environment, reabsorbed and repurposed into nature, in an almost vengeful act.

It’s worth returning to the idea of solastalgia, and how that will impact us in the future. It will be felt more and more clearly, becoming an intrinsic part of our experience as we are forced to adapt to the effects of the damage that we inflicted on the world. Garland’s work evokes this specific form of the uncanny by drawing attention to the wreckages that humanity will leave behind. In 28 Days Later, it’s our globally-recognised landmarks e.g. Westminster Bridge, Big Ben, and the deserted yet instantly recognisable streets of London. In Annihilation, it’s through hollowed out buildings and hollowed out men. The prosaic destruction disturbs because it implies that it could, and will, occur everywhere. Kane’s squadmate, the exploded man, was transmuted into something hauntingly beautiful. But Kane himself was just haunted, like his entire personality was scooped out of him, leaving a body, but nothing on the inside. Just as Lena is not owed explanations, we will be shocked by how fast and how completely the world will change over the coming years. Not necessarily a pleasant thought, to be sure. The world is changing, and, as Garland notes, it’s up to us to find a place and purpose for ourselves within that.