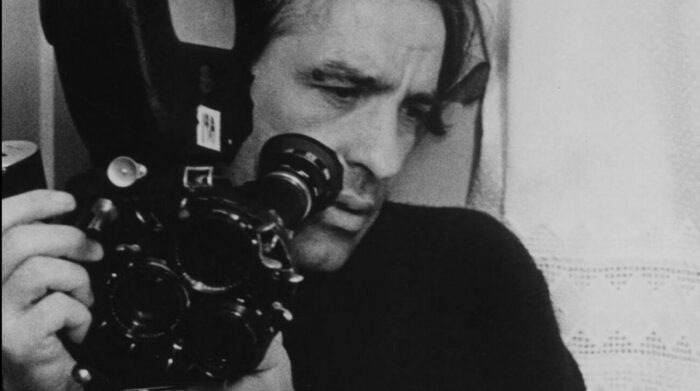

25YL/Film Obsessive writer Ashley Rincon explores the art and life of maverick independent director-writer-actor John Cassavetes in this retrospective series, beginning with his debut film, 1959’s Shadows.

Cassavetes loved moments when he could turn life upside down by doing the unexpected.

For John Cassavetes that was acting—the spontaneous creation of happy accidents that yielded surprising behavior and truthful moments. The quote above, taken from Marshall Fine’s Accidental Genius: How John Cassavetes Invented American Independent Film presents a way to begin to understand both what was important to Cassavetes and his approach to acting, and eventually, directing. A figure lionized by cinephiles, Cassavetes held such a steadfast commitment to his art, the search for truth in all his films, that he acted in many jobs solely to have money to make his films outside of the studio system’s interference. He was making movies, beginning with Shadows, in a time where more arthouse divisions of major studios didn’t exist to provide help and financing to artists who wished to make something outside of the Hollywood norms.

Cassavetes found ways to navigate this process himself, often taking out multiple home mortgages along with the acting gigs he took for the money to create his vision and pay his bills, as further discussed in Fine’s Accidental Genius. Many times, he had to come up with enough financing in these creative ways, not only to fund an entire movie’s production, but also to pay for its ad campaign and distribution. Cassavetes is often referred to as the father of Independent cinema because he navigated a path that didn’t exist to avoid a system he didn’t want to have a hand in telling his stories because he wanted his films to feel like life—difficult, upsetting, filled with unexpected strokes of fate, bad luck and misfortune—rather than the happy endings that seemed to dominate Hollywood story telling during his life.

Perhaps this commitment to the harsh and unpredictable realities of life was born in young John Cassavetes’ understanding of his father’s story. As an eleven-year-old, Nicholas Cassavetes would make the journey from Greece to the United States, with only his younger brother in tow and no plan or resources to gain entry or stay, and eventually wind up attending the prestigious Harvard University. Growing up under the shadow of his father’s story could only aid in cementing the idea that life is full of ups and downs, most of them unexpected, and can be made even more unexpected by being open to the possibilities of what can happen when one intentionally shakes things up.

As explored in Accidental Genius, Cassavetes life growing up certainly impacted his overall understanding of and perspective on how life could be experienced. When he was two, Nicholas Cassavetes moved his family—his wife Katherine, and his two young sons Nicholas and John back to Greece as the U.S. was experiencing The Great Depression. At eight years old, the family returned to the United States and John knew no English. Throughout the remainder of his childhood, John’s family moved around a lot and he had to find new ways to fit in and be accepted by his newest group of classmates. He often did this by becoming an entertainer to anyone watching. He would dance, do flips, make jokes—anything to get a laugh or a rise out people, always testing the limits of what could be expected.

With little academic ambition and solid hopes or plans for his future, Cassavetes reportedly entered the American Academy of Dramatic Arts to meet girls. Whether that’s true or among the lore of Cassavetes, he ultimately found himself exactly where he realized he needed to be, surrounded by a few wonderful instructors he connected with, and realized being an actor was the way he could make deep connections with human beings and explore the essence of humanity and truth among the many absurdities of existence. Despite all the meaningful connections he was making with, not just Gena Rowlands who would become his wife, but as well as with a slew of other creatives who would be a part of his circle until the day he died, he still felt like something was missing. He still felt stifled by the formalistic work that came with being an actor. Hitting marks so an actor would be lit enough for a scene, and the length of time it took to set up a camera to capture a shot he felt stifled the creative work of building a character. He longed for a way for those external preparations to be removed from an actor so they could do the incredible work of delivering a complex set of real human emotions.

The film that would eventually become John Cassavetes’ directorial debut, Shadows, began as an improv exercise he was conducting at the Cassavetes-Lane Drama workshop he founded with his friend and theatre director Burt Lane. The two sought new acting talent in New York that was interested in exploring the kind of real, complicated, human characters they imagined. The workshop provided a place for Cassavetes, a working actor at the time, to work on his craft and develop himself as an actor. This improv exercise that eventually birthed Shadows was meant to explore the insecurity of identity around Black people in the U.S., especially against the assuredness of identity among Black people in Africa that Cassavetes collaborator Erich Kollmar experienced while shooting a film on location there. Cassavetes had become fascinated with racial identity and race relations since working on two films and becoming close with Sidney Poitier in the early ’50s. he was interested in exploring the complicated feelings around race in the U.S. with segregation still dominating the south. Shadows‘ story was designed to explore three siblings with visibly different skin tones and their feelings about race and how it impacts their daily lives. He also wanted to examine the reality of two characters’ very different relationships to passing.

Shadows follows three siblings on very different journeys as they live together amidst the New York beat scene of the late 1950s. Hugh (Hugh Hurd), the oldest brother. is a singer struggling to get gigs and regular performing jobs in venues that will recognize his talent. Hugh is the darkest of the siblings and recognizes how difficult his journey is, especially in gaining access to clubs and restaurants that are not only interested in his singing but would like to exclude his Blackness. His manager, Rupert (Rupert Crosse) seems to be the only one that believes in his talent and knows that the jobs he’s being offered, as well as the money coming with them, are beneath his client and friend’s talent. Benny (Ben Carruthers) is the middle sibling who is wondering through his life quite aimlessly. His daily routine is scrounging up enough money to run around with his friends at night bouncing from place to place trying to meet girls to entertain for the evening. He is lighter in skin tone than Hugh but perhaps cannot pass everywhere as a white man and seems conflicted about his place in the world as he is constantly melancholic and seems to be searching for something else while also not sure of what that is. Lelia (Lelia Goldoni) is the younger sister of the two boys, a naïve 20-year-old full of vigor and certainty about what her life will become. Lelia is incredibly light-skinned and passes as white in every circle she places herself among. She does not have to think about her racial relationship to the world like her brothers do and has little trouble gaining acceptance wherever she wishes to be.

Lelia, with all her brazenness and tenacity must contemplate the way she is seen by the world when, after she sleeps with a man for the first time, she watches him realize she is Black by encountering her brothers when he comes by her house. The awe, surprise, and examination immediately wash over Tony’s (Anthony Ray) face as he is also forced to reckon with why he had such an intense reaction. As he makes up a reason why he has to immediately leave the apartment, Hugh, who can see exactly what is going on, kicks him out and forbids him from seeing his sister again. Lelia spends the next couple days in bed crying and smoking cigarettes, internally dealing with something that everyone can see but she has had little direct interaction with—someone, at least initially, not wanting to be with her because of her Blackness.

She finally gets enough strength to put on the persona she has been wearing for what seems like her entire adult life and go to a dance with a dark-skinned Black man. As soon as her date Davey (David Jones) arrives, Lelia berates him for not bringing her flowers, then has him wait for her to get ready for three hours, aimlessly and with many interruptions, before finally leaving for the dance. Once at the dance, Davey checks Lelia on her attitude and sense of privilege informing her, although indirectly, that the attitude she has is off-putting and not befitting of someone whose company he will continue to seek. For the second time, we see Lelia visibly shaken, as none of the white men that she usually shares her time with would ever think to scold her in this way and would doubtfully never have these thoughts at all.

Cassavetes certainly captures the lack of assuredness as it relates to race he wished to explore through Shadows. Each of the siblings shows a lack of true confidence in their racial identity. Hugh proclaims to want to be taken seriously as a musician many times throughout the film, but what he is really saying is that he wants to be treated like a white musician in 1959. He doesn’t want his music to be an afterthought because he books a gig at a club to introduce dance numbers. Hugh seems to want to have his Blackness ignored in white spaces and he wants to have the room to not accept jobs that he deems beneath him and still have a plethora of options. Rupert many times has to implicitly tell Hugh that he is doing the best that he can to get his music heard but is limited by racist attitudes and assumptions and that he is going to have to stop turning down what work he can find for him if he ever wants to sing.

Benny shows his hesitation about who he is to both himself and the world by going about his life so directionless, until nightfall when he joins his white friends to try to go pick up white women. He doesn’t associate with anyone on a regular basis that can relate to him and understand the problems he deals with on a day-to-day basis as a Black man that can often but not always pass for white. This struggle and lack of real connections with other human beings seem to be the reason he is often seen sullen or melancholic throughout the film. Lelia, shows her lack of assurance with herself through her dating life. She constantly surrounds herself with white potential romantic partners and turns down any Black man suggested to her by the few Black friends that she has. She has grown accustomed to being seen as white in almost every space that she occupies. She has taken on the behaviors that she associates with whiteness and is often greeted with success in the form of multiple men vying for her attention. Each of them seems to attempt to suppress their true feelings surrounding their race while refusing to be honest about them until a situation forces them to be.

The plot of Shadows is ambitious for the pre-Civil Rights United States of 1959, even more so thanks to Cassavetes desire to explore the complex themes of race and passing without ever mentioning the word race or having these kinds of conversations take place between the characters explicitly. Also remarkable for its technical achievements, many of which occurring simply because there wasn’t enough money to make the film any other way. For instance, the majority of the sound captured in the film was done so on location as the cameras rolled as there was little budget for sound mixing in post-production, per industry standard. The on-location street scenes seem so lively and energetic because they are; they are real people going about their lives and interacting with the city. John Cassavetes didn’t secure any permits to shoot on location, nor hire any extras for these scenes so a sense of authenticity is created through the final product.

Shadows was funded either by donations, thanks to a radio spot Cassavetes appeared on in which he asked the listening audience to send in contributions to see a film get made that took a new angle on racial relationships. With Shadows Cassavetes created a template for what independent film in the U.S. would become—personal artistic expression in movies that took chances and played with form that was still recognizable as a film. He focused on characters first and plot second and got his film seen entirely on his own with no Hollywood interference. Cassavetes made his story about people living in the shadows of society, refusing to or being too scared to put themselves into the spotlight. He did whatever he had to do with whatever resources he had to fulfill his experiment, while setting the stage for a new generation of filmmaking and even inspiring young NYU student Martin Scorsese that “cinema could be made anywhere.”

Ashley Rincon’s John Cassavetes Retrospective will continue with an examination of his 1968 film Faces.