With Matt Reeves’ triumphant The Batman winding up its theatrical run and hitting streaming services, let’s talk about the Batman film against which Batman films will be measured from now until the end of time: Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight. Closing in on fifteen years after its release, there’s still very little dispute that The Dark Knight still stands not just among the greatest superhero movies ever made, but one of the greatest movies of the 2000s altogether. Similar to The Dark Knight Returns, it’s a monumental achievement of storytelling against which every other Batman story in the medium is ultimately compared—and, also similar to that story, it’s full of messy politics and morality that has… not always aged well, particularly when it comes to the problem of domestic mass surveillance presented at the film’s climax.

Now, politics and comic books/comic book movies have had a long history regarding politics—the cover of Captain America’s comics debut had the character punching Hitler while Iron Man started off as an anti-communist hero fighting Vietnamese agents, and more substantive works like V for Vendetta would explore mature, thought-provoking questions like whether or not terrorism could ever be justified against a fascist, totalitarian state.

Generally, the political messages one finds in comics tend to fall into one of two camps: specific references that are overly simplistic—Captain America punches Hitler because Hitler is Bad—or more complex and thought-provoking while simultaneously being more abstract and open-ended—V for Vendetta is certainly inspired by Alan Moore’s opinions on the Thatcher government, but it’s not just about the politics of that era but about the very idea of totalitarian states and the fight against them. This dichotomy has helped ensure that, for the most part, said political messages have aged fairly well: very few people will argue that Hitler is not Bad and didn’t deserve getting socked in the mouth by Captain America, while V for Vendetta still inspires debate and discussion to this day.

In contrast, The Dark Knight finds itself in a third camp, occupying a middle ground between the two: there are very specific references here, but they’re of the complex, morally grey type—and as a result, some of them have not aged well. It’s fairly well known by now, but The Dark Knight is full of thinly veiled allegory to the War on Terror, in particular the actions of the Bush administration during said War on Terror. Later on, President Barack Obama would even cite the film as a way to explain how he saw the role of ISIS and the environment that allowed the group to emerge: “‘There’s a scene in the beginning in which the gang leaders of Gotham are meeting,’ the president would say. ‘These are men who had the city divided up. They were thugs, but there was a kind of order. Everyone had his turf. And then the Joker comes in and lights the whole city on fire. ISIL is the Joker. It has the capacity to set the whole region on fire. That’s why we have to fight it.'”

Some of these parallels have fairly straightforward outcomes that make director Christopher Nolan’s intended message about them clear. Batman’s “enhanced interrogation” of Joker to try and find the locations of Harvey Dent and Rachel Dawes ends in utter failure—Joker intentionally gives him the wrong locations for each of them, and it ends with Rachel’s death and Dent’s disfigurement and hospitalization. Enhanced interrogation does not work, enhanced interrogation bad.

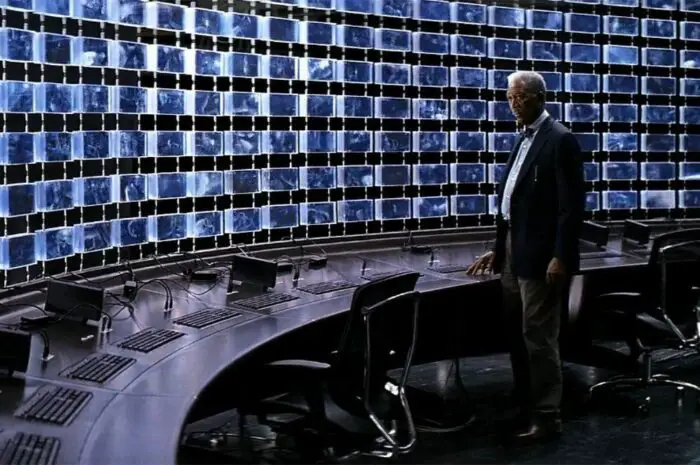

But some of them sit in more morally grey territory, and unfortunately, that includes the most critical—and in hindsight, controversial—parallel, coming at the climax of the film. With the deadline on the Joker’s latest threat fast approaching, Wayne Enterprises CEO Lucius Fox gets informed of a break-in at Wayne Enterprises’ R&D department. Making his way there, he finds a fully geared-up Batman, standing behind a virtual wall of screens displaying a real-time sonar feed of the entirety of Gotham City. Yes, this is “Batman does mass domestic surveillance.”

“Beautiful. Unethical. Dangerous,” is Lucius’ response. As he explains it, Batman has effectively turned every cell phone in Gotham into both a microphone and a high-frequency generator receiver, allowing him to scan the entire city to find where Joker is hiding and pinpoint his location using a previously obtained voice sample—while also listening in on virtually all of Gotham’s citizens.

This fact isn’t lost on Lucius, who word for word says “this is wrong,” holding his ground when Batman says that he has to find Joker. When Batman explains that it’s programmed so only he can access it, Fox tells him that spying on thirty million people isn’t part of his job description—and that Batman should consider the machine’s presence at Wayne Enterprises to be his resignation. The scene ends with Batman’s final instructions to Lucius—to type in his name when finished—but the last piece necessary to understanding this scene doesn’t come until later.

The Dark Knight ends with a Batman monologue delivered over a montage of each of the main characters in the aftermath of the film’s events: Gordon making a speech at a memorial for Harvey Dent and smashing the Bat-Signal with an ax, Alfred burning Rachel’s letter to Bruce telling him she planned to marry Harvey, and Lucius following Batman’s instructions to type in his name, leading to him smiling with approval as his name triggers a self-destruct mechanism in the machine. When we get to the scene with Lucius, the line accompanying it is “sometimes people deserve to have their faith rewarded.”

The use of the word “faith” is crucial here, as it more explicitly connects the mass surveillance scene to a well-known philosophical principle regarding faith: Søren Kierkegaard’s principle of the teleological suspension of the ethical. In the simplest terms, it’s the idea that sometimes faith calls us to set aside normal ethics and morality in order to serve a higher purpose we may not understand. The most well-known example of this is the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, in which Abraham is ordered by God to kill his son Isaac as a sacrifice—Abraham knows that murder is wrong, but he must be prepared to do it as it is what God commands, in order to fulfill the divine purpose in a way to which he is not aware. Just as Abraham had his faith in God rewarded—God not only spares Isaac’s life, but tells Abraham that he will be the “father of nations”—so too is Lucius’ faith in Batman rewarded by the self destruct sequence, preventing further usage and potential abuse of the system, and perhaps no part of The Dark Knight has aged as poorly as this one has.

Originally, the problem I held with the mass surveillance parallel was that it felt like Nolan wasn’t being clear as to what he thought of it, that he wanted it to be ambiguous as to whether or not it was the right thing to do. But after a recent rewatch, my view on it has shifted subtly, but substantially: Nolan is clear in the message he wants to deliver on the matter, the problem is that he wants to have it both ways. He wants to say that yes, the mass domestic surveillance authorized under the Patriot Act was morally wrong, but that it was also justified in order to deal with the greater threat of terrorism—and on top of that, that this suspension of the ethical ultimately leads to our faith being rewarded, not only in the greater threat of terrorism being dealt with but in knowing that we can trust that the people who have access to these systems will do the right thing and not abuse these capabilities.

This… was not the case, to put it lightly. Thanks in part to classified documents that were leaked to the public in 2013, there’s now a surprisingly clear picture of the outright horrifying degree to which the NSA had monitored the communications of millions of Americans: millions of Americans’ phone records, thousands of Americans’ emails, and even going so far as to work with the likes of Google and Facebook to monitor online chats and web browsing. Court rulings would determine that this surveillance went far beyond what Congress intended to permit with the Patriot Act and revealed a multitude of abuses, while the revelations seemingly confirmed the belief of many critics that the surveillance violated American’s rights under the Fourth Amendment—protection against unreasonable searches and seizures.

On top of that, what is effectively a new surveillance state rose up in the meantime, that of the Facebooks and Googles of the world, harvesting just about every piece of information people were willing to put online in order to more effectively target them with ads. This allowed for entirely new systems ripe for abuse—Facebook in particular has been riddled with scandals for years now, regarding everything from how its systems were exploited by foreign adversaries to interfere with U.S. elections to an experiment conducted by the company’s own engineers to determine whether or not they could influence people’s moods by giving them more positive or more negative posts.

In the wake of these revelations, this piece of The Dark Knight‘s political and moral message seems almost laughably naïve—and it’s arguably the most important one in the film. It’s the moral problem that comes at the film’s climax. While one can argue as to the effectiveness of mass surveillance in regards to stopping terrorism, the idea that mass surveillance was something that would only amount to a temporary suspension of ethics for a greater good and that we could trust the people conducting mass surveillance to not abuse these systems comes from a mindset that simply could not exist in 2021.

The Dark Knight is still by all accounts an impressive film. But the almost idealistic notion it holds regarding mass surveillance doesn’t just make it a significantly more uneasy watch in 2021, but makes the film feel uniquely dated—not just from close to fifteen years ago, but from a different world altogether.