Wes Anderson’s upcoming film, The French Dispatch, arrives in theatres next month. It’s inspired by the editors, reporters, and early days of The New Yorker. An exciting premise, though it comes as no surprise—Anderson’s films have always gravitated towards the kind of high-brow culture the magazine represents. In anticipation of the movie’s long-awaited release, I decided to take a look back at his filmography. Below is my (sole, personal, aiming to please no one but myself, subject to change in the coming years) definitive ranking of the Wes Anderson films.

The Worst

9. Rushmore (1998)

Max’s delusions of grandeur, unsuccessful love affairs, and social awkwardness make this movie hard to watch. It’s a coming-of-age movie I can’t relate to given its hyper-masculine lens of adolescence. The male obsession with competition is the driving force behind much of the plot. A 15-year-old boy and a 50-year-old man compete for the affection of a teacher. They fill a room with bees, repeatedly drive over the other’s bicycle, and cut the brake cables on a Bentley. Rushmore even manages to focus on small, heartbreaking moments in a failing marriage. In one scene, Bloom (Bill Murray) aimlessly throws golf balls into his swimming pool as his wife flirts with her tennis coach.

While the eventual reconciliation between Max and Bloom gives us deeper insight into their backstories, it doesn’t redeem how insufferably deluded the two main characters are. Plus, Max’s love affair with the teacher is absurd, especially when framed as an integral part of his emotional development. It’s dead last in my ranking of Wes Anderson.

8. Bottle Rocket (1996)

Anderson’s first feature film stars Owen and Luke Wilson as two friends plotting to rob a bookstore. They hope to work with a local thief for just long enough to establish the means to support themselves. The bookstore robbery serves as an extended comic relief piece and embodies the film’s sense of humor. Here, Anderson doesn’t take himself too seriously, yet Bottle Rocket is still littered with classic Andersonsonian touches (take, for example, the friends’ “75-Year Plan” notebook).

It’s apparent that Anderson and co-writer Owen Wilson used this movie to develop their comedic voices, absurd dialogue, and knack for visual details. These qualities would go on to define Anderson’s oeuvre. It may not be fair to compare Bottle Rocket to Anderson’s later work, but this movie just isn’t what I put on when I’m in the mood for a Wes Anderson film, so I have to rank it low. It lacks his symmetrical framing, playful color palettes, and clever dialogue. Its legacy lies in being the film that gave the director enough name recognition to get backing for future projects. But at least it’s not Rushmore.

The Meh

7. Isle of Dogs (2018)

There’s so much potential with this one, but the plot is too absurd to ignore. The film takes place in a dystopian Japanese city 20 years in the future. An outbreak of canine influenza leads the government to banish all dogs to a distant waste island. The mayor’s orphaned nephew steals a plane and flies to the island to rescue his dog. After crash-landing on the island, a pack of abandoned dogs try to help him search for his lost pet. The movie plays out signature Anderson tropes, including a tragic childhood and a team fighting before reuniting.

The “big twist” lies in the government manufacturing the dog flu outbreak. Their motive? To eliminate all dogs. Why? They’re cat-lovers. Ok, sure. (Kind of has The Amazing Spider-Man vibes, in which, for those of you who don’t remember, the villain plotted to turn New York’s population into lizards.) It’s a bad premise that distracts from an otherwise good movie. The innovation of Isle of Dogs lies in its stop-animation form, but it has little to offer beyond its meticulously crafted aesthetics.

6. The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

Steve Zissou: an oceanographer determined to capture and kill a rare shark that ate a member of his crew. In typical fashion of Anderson’s characters, Zissou is a selfish, opportunistic drunk, yet somehow loveable despite his flaws. Perhaps this is because Zissou explores an underwater world we imagined as children and quickly tucked away upon reaching adolescence. A lot works here, but The Life Aquatic, I would controversially say, is the most overrated of Wes Anderson’s films, ranking in my bottom half. If not for Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson) showing up claiming to be Zissou’s long-lost son, the movie would be a series of fun events barely held together. His presence adds the only sense of humanism to the adventure.

In the end, the movie is fun, but not usually anyone’s favorite. Mostly, I appreciate the character given to the Belafonte—especially the “let me tell you about my boat” scene, where we’re introduced to the ship via a long take of its layout. The boat not only has an engine room: there’s also a dedicated room for editing documentaries, a sauna and masseuse, and a reading nook resembling a tiny submarine at the ship’s bow. When the crew goes underwater, they become reliant on the ship’s safety among the hostile waters. It helps the boat to become its own character and enables it to be the center of the adventure. I also love the underwater scene where the crew sees the jaguar shark as Sigur Ros’ “Staralfur” plays in the background.

5. Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Two 12-year-olds, both eccentric outcasts in their communities, unexpectedly meet, fall in love, and run away to be together. It’s a sweet plot only made better by the symbolic use of color. Yellow permeates nearly every scene of Moonrise Kingdom: yellow costumes, furniture, filters, and wallpapers feature prominently throughout the movie, always situated between various shades of pastel. The light colors emphasize the innocence of the two protagonists. Cooler shades only come into play during particularly tense scenes (for instance, when Suzy’s parents sleep alone at night in separate twin beds). The cinematography is playful and fun to analyze.

While Moonrise Kingdom is a beautiful visual experience, I always found the sexualization of Suzy off-putting. Sure, she and Sam share in their sexual awakening on the beach, and the children are written to behave like adults. But these themes are taken too far when Sam gropes her breasts—covered by a training bra—as she assures him they’ll grow soon. It’s one of the few instances in which Anderson’s juxtaposition of bright colors with serious dialogue felt more inappropriate than humorous.

The Best

4. The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

The premise: an ensemble of misfit sons coming to terms with their father’s recent death on a trip across India. It’s tongue-in-cheek, funny, and heartfelt. Take, for example, that the brothers try to save local kids from drowning, but end up accidentally killing one and attending his funeral. Anderson’s reverence for the foreign setting is clear, as the on-scene locations make this a visually different experience from, say, Isle of Dogs or The Life Aquatic. The background minutiae isn’t so meticulously crafted, leaving us with more room to recognize Anderson’s powerfully written characters. Over time, the movie reveals their complex family dynamic, replete with an estranged mother, sibling rivalry, and a hierarchical family arrangement leftover from childhood.

Adrien Brody and Owen Wilson carry their roles with endless charm and wit. Soon, their characters realize that one cannot force a spiritual journey, just as one cannot force friendship between family members. It’s a heartfelt exploration of our relationships with our closest relatives, examining not only the conflicted dynamics between brothers but also how parents add to the divide between siblings. Plus, the soundtrack features songs from Satyajit Ray and The Kinks to punctuate important moments. The final scene consists of the brothers running to catch their train in a slow-motion sequence, discarding all their suitcases gleefully as “Powerman” plays in the background. Given how adroitly it tackles family dynamics, it’s high in my ranking of the Wes Anderson movies.

3. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

The Royal Tenenbaums—a fan favorite. It’s a surprisingly sweet story of familial love. Each sibling returns home for the first time in 20 years to remedy past traumas before their father’s death. Royal’s ex-wife, Etheline, is engaged to an academic whose love she was blind to for over a decade. The adopted daughter, Margot, is an emotionally isolated literary genius who has hidden her smoking habit from her family since she was 12. Chas can’t grow past his arrested development once his wife dies in a plane crash. Richie equates his fallen tennis career with his father’s absence and inability to marry Margot. The film has a general sense of hopelessness surrounding the characters’ ability to grow past their shortcomings. Yet we root for them anyway.

It’s a paean to second chances set in a tumultuous, upper-class milieu. With all the siblings living in their childhood home, the director uses the space to nostalgically render their past. The discovery of a decades-old cigarette pack hidden within a chimney brick adeptly represents Margot’s lifelong isolation. And for all the literary references, the movie makes space to poke fun at the scholarly worldview of its characters. Plus, the iconic costume design comes replete with three red Adidas tracksuits and a mink coat on a blonde goth. The final piece is a humbling, witty film about mortality and forgiveness.

2. The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

The titular hotel sits atop the mountains of Zubrowka, a fictional country ravaged by war, recalling 1930’s Europe. But The Grand Budapest Hotel’s plot is oddly delightful, despite the recurring calamities. Monsieur Gustav H., the hotel’s concierge, inherits a priceless portrait from a deceased lover. In order to get the painting back, her corrupt relatives frame him for her murder. As Gustav runs around Eastern Europe trying to clear his name, he also plays matchmaker between his protégé and a local pastry chef. Their romance becomes the crux of the plot. Unexpectedly, the film ends with the young couple’s descendent reading the story of her family’s legacy.

I have a soft spot for movies that take place in one cinematic location (like the bathhouse in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, or the castle in Lanthimos’ The Favourite), and The Grand Budapest Hotel is no exception. The hotel is the obvious marvel of the movie, and it benefits from Anderson’s abstract formalism. Colors communicate the state of the hotel over time: bright reds, rich purples, and soft pinks mark the hotel’s heyday. Then, its later years contain burnt orange, drab green, and wood tones. At the same time, the aspect ratio changes in order to suggest the time period and mood. The 1930’s scenes, for example, are shot in the square Academy ratio, mirroring the films of those eras. We know all we need by the evolution of the movie’s cinematography. Every costume and set goes beyond what is expected—or even necessary. Yet this dedication to detail is precisely what makes it such a memorable story.

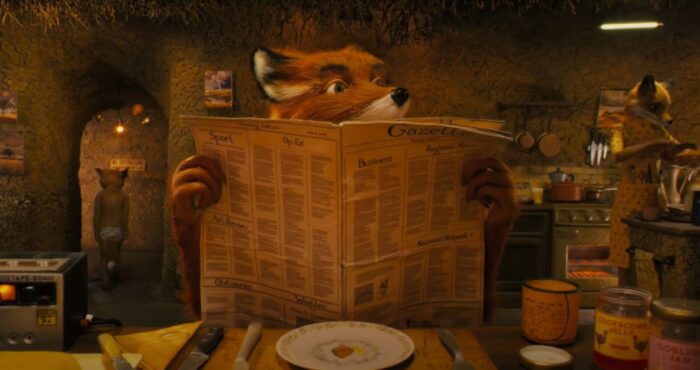

1. Fantastic Mr. Fox (2014)

Combining Dahl’s distinctly mature, darkly comedic children’s stories with Anderson’s bright and playful color palettes creates a unique cinematic experience. Of all the Wes Anderson movies, this one’s my favorite, and I’ve ranked it at the top for many years (I’ll confess that it’s in part due to my love of Roald Dahl stories). The stop-motion characters and hand-crafted landscapes resemble a picture book come to life. The art design is definitely a large part of the appeal—it even received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (losing to Up). In many ways, Fantastic Mr. Fox is exactly what one might picture when they imagine a stop-motion Anderson film, given its immaculately arranged camera pans, thought-out set design, and soundtrack of classic rock.

But the movie isn’t all aesthetics: the plot behind these carefully designed scenes involves a husband slipping into his old thieving ways, and a community banding together for protection. The Fox family shares similarities to the Tenenbaums (with yet another lying father, fed-up wife, and emotionally stunted son). Anderson once again pulls off a movie that blends tender humanism with looming existentialism. These characters grapple with their inherent nature and learn to accept each other as they are. It’s more playful than some of his prior installments, proving itself comically self-conscious of the techniques Anderson falls back on time and again. Also, casting George Clooney as Mr. Fox was, I think, the perfect choice.

Over the course of a 25-year career, Anderson has managed to perfect the cinematography and dialogue we first saw him experimenting with in Bottle Rocket. He’s honed his personal style and made a reputation for himself as a meticulous leader and director (which is probably why I ranked newer Wes Anderson films higher). With The French Dispatch set to release next month, Anderson’s next installment looks like it will not only return us to his iconic aesthetic but also serve as an homage to the art of storytelling. Gone are the days of coloring a pretty picture and throwing in a band of misfit journeymen: here we seem to have something more akin to The Grand Budapest Hotel, in which his characters and color palettes feed into a larger message about history and our own insignificant existence. I, for one, am excited to see how it holds up compared to his previous work.

Calling anything by Anderson ‘hyper-masculine’ is missing the point.

I have to think this ranking is a function of the age of the reviewer when they came into familiarity with Wes Anderson. I don’t think there’s justification otherwise, unless it was meant as clickbait.

I don’t know, I see Brianna offering reasons here. Perhaps you just disagree? That would be fair. I don’t think there is any real objective standard or something. These are her rankings, her favorites and the ones she thinks are less good. I don’t think she’s far off personally, but that is just my opinion. We could discuss our opinions with reasons if you were so inclined