When you hear the name Martin Scorsese what do you think of? Dark hangouts bathed in red light where silk-suited shady characters with puffed-up hair gamble and sip drinks all night long? Gatherings where they hope everyone keeps their temper in check before the shovels have to be hauled out?

Do you think of guys like Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci threatening an underling, cop, banker or politician with a bat to the head or something worse if they don’t go along with whatever scheme they have going on in Goodfellas or Casino?

Do you think about the quiet, introspective portraits of faith and tortured souls in conflict with the rules and traditions inhabited in the societies of The Age of Innocence, Kundun and Silence?

Do you think of the tortured talented artists consumed by ego and lust for fame which are portrayed in The King of Comedy (a major inspiration for this fall’s billion-dollar hit Joker), The Color of Money and the “Life Lessons” segment from New York Stories?

How about the Scorsese who explored the lives of such figures such as Jesus, Howard Hughes and of course, Jake La Motta, brought their stories to the screen and didn’t shy away from making them look less than wonderful?

And there are still more Scorsese movies I haven’t mentioned yet—Boxcar Bertha, Mean Streets, Hugo, The Departed, Bringing Out the Dead, Gangs of New York—each one different and original but all from the mind, heart and soul of Scorsese, one of our most dynamic filmmakers ever.

Here are my ten personal favorite Martin Scorsese films. I left off Mean Streets and Gangs and Departed but that doesn’t mean I don’t love them. These are the titles (in release order) which dazzled, inspired and hit me on one or several emotional levels. Also, at the time I compiled and wrote this list, I had not yet seen The Irishman and this is why it’s not included on here.

Who’s That Knocking At My Door (1967)

Martin Scorsese’s very first feature Who’s That Knocking at My Door is a tremendous debut. A scrappy, episodic riff on Fellini’s I Vitelloni about a young New Yorker named J.R. (Harvey Keitel) who meets a girl (listed onscreen simply as “the girl” played by Zina Bethune) on the ferry one day. J.R. also likes to hang around with a batch of petty punks who have no real goals in life but to pull small cons and drink. J.R. separates that life from the girl by taking her to John Wayne movies and then back to his place.

When the girl confides to J.R. that she was the victim of a rape by a previous boyfriend this becomes too much for him to come to terms with. In his religious views, she is no longer pure (even though J.R. himself, has no issue romping around in bed with other women.) J.R. struggles with his feelings for the girl and decides he can “forgive” her—at which point she rejects him and he lashes out at her, then joining his friends for a drinking night and ultimately to a church, where he finds no answers.

All of the themes Scorsese would explore through his entire career are introduced here: loyalty, guilt, religion, the street life and conflicts involving love, sex and self doubt. The image of J.R. cutting his lip open as he kisses the feet of a statue of Christ is one that will figuratively present itself in future Scorsese movies: you will either bleed for Christ, bleed in love or bleed in the streets. Either way, in life, you pay with your blood. No filmmaker in history has understood this better than Scorsese. None ever will.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Here is an example of a Scorsese character bleeding out of love and every minute is an absolute pleasure to watch. After Who’s That Knocking, Boxcar Bertha and Mean Streets, Scorsese did something surprising to not only film audiences but for himself: he made a movie about someone who understood a heart can’t survive in a world surrounded by violence.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, written by Robert Getchell, is the story of Alice Hyatt (a tremendous Ellen Burstyn), a housewife who leaves behind an abusive relationship with her ten-year-old son, Tommy, with no plans and little money. But they have a car and Alice has a legitimately talented signing voice. Alice manages to land a job in a dive country/western bar but that doesn’t last long once she gets involved with another violent sociopath (a terrific Harvey Keitel) who just happens to be married. Alice then finds work at a diner in Tucson and begins seeing a rancher named David (Kris Kristofferson).

There’s much which makes this little movie special from the performances to Scorsese’s restless camera to Marcia Lucas’s editing and the award winning lead performance by Burstyn, who plays Alice as someone who keeps getting kicked by life, yet somehow still carries a song inside her soul.

Taxi Driver (1976)

Here we go from Alice Hyatt’s song in her heart to Travis Bickle and the poison festering in his. Imagine the shock that editor Marcia Lucas must have had when she began seeing the footage from this movie coming off of Alice.

Written by Paul Schrader, Taxi Driver was first given to Brian De Palma to make into a feature. However, the filmmaker decided to make Carrie instead and Scorsese was introduced to the writer who agreed to make Taxi Driver. Schrader drew on his experiences prowling the dirty streets of New York during his bouts of insomnia and found it to be a surreal place to be during this time. There were shell-shocked young men returning from Vietnam, Watergate in the culture and the emergence of all-night pornographic movie houses. While living on cigarettes, stale movie theater candy and cola, Schrader developed an ulcer and in the hospital realized he hadn’t spoken to anybody in weeks.Taxi Driver was written from there.

The movie’s main character drives a taxi, which isolates him from most everybody else in society. When he attempts a relationship with Betsy, a blonde political volunteer, it goes horribly wrong. With that rejection, Travis realizes he’ll always be rejected by the society he longs to be a part of—one which exists far away from the stink and rot populated by the pimps and deranged beings he encounters every night. Without a purpose of living a life of normalcy (finding a girlfriend to be happy with), Travis creates his own purpose and this is where violent thoughts manifest into his life. Betsy could have saved him from his thoughts but without her, Travis strikes out to make an unhealthy mark.

Travis may be created from Schrader’s imagination but Scorsese related to the character in his own way (much like Travis, Scorsese felt like the mainstream movie industry would always reject him) and he knew he needed an outlet. For Scorsese, that outlet turned out to be making movies and this is what saved him. One wonders if Travis’s path would have been different had he attempted something similar?

Raging Bull (1980)

In between Taxi Driver and Raging Bull came New York, New York, a flat musical romance starring De Niro and Liza Minnelli which died at the box-office upon release. Scorsese went through a deep depression as his passion-project was ignored by the public who were flocking to see Star Wars and Close Encounters, movies made by good friends of his. To alleviate the sting, Scorsese indulged in drugs which landed him in the hospital where he would lie and wonder if there was a place for him in the industry.

De Niro came calling with a script he wanted made: Raging Bull, the story of boxer Jake La Motta, a brutish, short-tempered fighter whose life outside the ring was more confrontational than inside. It was a great metaphor for the director who only really felt in control of himself while making a movie. The rest of it, including audience interest, was out of his control. La Motta lost control of every bit of his life but Scorsese didn’t. He exorcised his demons in the making of this movie and came out alive.

With this movie, he welcomed a new collaborator: editor Thelma Schoonmaker who has edited every movie of his ever since up to and including The Irishman. Scorsese has been accused in the past of not telling female stories, but this ignores the fact that since 1974, his editors have been female and these movies are every bit their stories as his. Schoonmaker won her first Oscar for her work here and would win twice more for The Aviator and The Departed.

Raging Bull earned enough acclaim that it kept Scorsese in the club. He went on to make The King of Comedy and then he was gearing up to make the movie he really wanted to make—The Last Temptation of Christ.

After Hours (1985)

Scorsese was set to begin The Last Temptation in early 1984 but learned the previous Thanksgiving that his deal to make the movie with Disney fell through. At the encouragement of De Palma, the director licked his wounds and went back to his low budget roots.

Made for just $4.5 million from a script by 26-year-old Columbia student Joseph Minion, After Hours can be viewed as the darkly comedic flip version of Who’s That Knocking at My Door. Both movies are about seemingly decent men (with low levels of tolerance for annoyance) who just want to meet a nice girl. However, whereas Who’s That Knocking’s J.R. drives the girl away with his insecurities, the girl here, Marcy (a never more ravishing Rosanna Arquette), spooks her date, Paul (Griffin Dunne) away before it’s even over.

Both movies suggest nothing good can arise from either situation. While J.R. wrestled with his faith and affection, Paul wrestles with a very different dilemma—he just wants to go home, but the city is working against him in every way imaginable. From stubborn subway attendants, jealous bartenders, dippy waitresses, a sculptress/dominatrix, a snide ice cream truck operator, getting his head shaved inside a punk club, a mob of vigilantes out to get him and a pair of petty thieves (played by Cheech and Chong) he can’t stop running into, Paul finds his night turning into a real life nightmare. Poor Paul. If only he had found an ATM machine!

After Hours is a movie about the unpredictable night life of New York and the oddballs who inhabit it. One wonders if Paul actually did finally make it back home the next night—inside where it’s safe—or if he decided to try his luck once more in the hopes of meeting another girl. In Scorsese’s New York, anything’s possible.

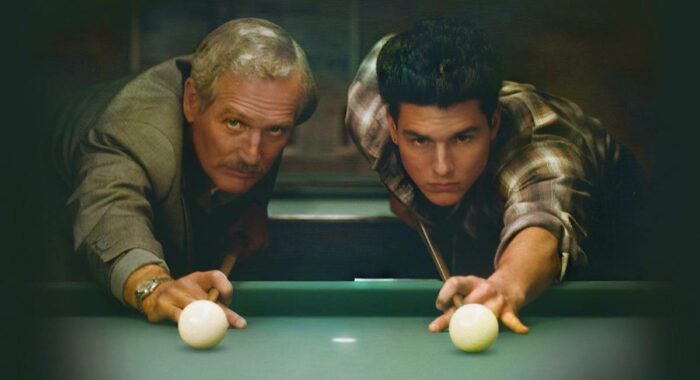

The Color of Money (1986)

After Hours had shown audiences what an invigorated Scorsese was capable of making and the industry had taken notice. When Touchstone was looking for a director to make The Color of Money, a sequel to the Paul Newman classic The Hustler, Scorsese was chosen because of his ability to herald great work from actors while demonstrating an unmistakable flare for visual storytelling.

The Color of Money is much more than the movie Tom Cruise made before Top Gun. It’s a taut and terrifically entertaining (for the most part) exhibition of ingenious camera work, editing and pacing. While the movie is book-ended by a leisurely set up and conclusion, everything in-between flies as fast as a Chicago train.

Filmed during the dreary, slushy winter of 1986, the cinematography by then Scorsese regular Michael Ballhaus perfectly captures the sluggish feeling of those dark months, and editor Schoonmaker sustains the picture’s energy with some brilliant cutting to some choice music tunes (the swirling camera accompanying Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London” is one of the movie’s most astonishing moments).

The movie was a box-office hit and earned Paul Newman a Best Actor Oscar. Studios wanted the director for their projects but he only had one project in mind and it would be the most challenging project he’d ever faced.

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

The book Hollywood Under Siege goes into great detail about the difficulties Scorsese faced in making The Last Temptation of Christ, from budget constraints to a tight shooting schedule which began just before Halloween 1987 and wrapped (incredibly enough) on Christmas day of that year.

Then before the movie was even completed, it was attacked by members of the religious right as “blasphemous” and protests (not to mention a death threat or two) were held not only against Scorsese, but against Universal Studios (who were financing and releasing it) and any theater which agreed to show it. Never mind that these people had not yet even seen the movie—and they probably still haven’t.

Based loosely upon the novel by Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis, The Last Temptation of Christ takes a different look at the life of Jesus of Nazareth (Willem Dafoe giving the performance of his life) than previous movies had. This Jesus is guilt-ridden, prone to violent outbursts, full of doubt, and asks questions about his place in the world. Previous screen versions of Jesus have offered a different portrait—one who’s confident, radiant and there to due other’s bidding. Scorsese’s Jesus is just a man with the same feelings and uncertainties we all have. Perhaps it was this concept of Jesus that evangelicals negatively responded to and less to do with the three minute long “sex” scene between Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Much screaming has been made about this scene while its critics missed the point completely. It’s a love scene in every sense of the word. Jesus loved Mary, loved the idea of having a family with her and living a peaceful life. Much like all of us. Loving and raising a family was not his purpose though. Jesus fulfills his role on the cross where he encounters an angel (Juliette Caton) and tells him God is pleased with him and from there, we watch an alternate reality showing Jesus as a family man well into his old age.

Scorsese had wanted to make this movie for many years and to do it, he compromised on budget and made the movie on a much smaller scale then he wanted. At the same time, Bernardo Bertolucci was making The Last Emperor with thousands of extras and Spielberg was making Empire of the Sun with even more extras, while Scorsese had to make do with less than a hundred. I think the smaller scale works in the movie’s favor as it feels more intimate this way and we feel Jesus’s pain more effectively.

Visually, it is one of the most arresting movies ever made. The desert scenes feature some of the bluest skies I’ve ever seen on film. Schoonmaker’s editing is once again revelatory, and the score by Peter Gabriel is an incredible work featuring Middle Eastern sounds and flavors.

Getting the movie made through all the turmoil was not easy on Scorsese and still wasn’t after its release in August 1988. One prominent religious spokesperson, Mother Angelica, founder of Eternal Word Television Network called the film “the most blasphemous ridicule of the Eucharist that’s ever been perpetrated in this world and a holocaust movie that has the power to destroy souls eternally.” The movie was banned in many countries such as Greece, Turkey, Chile, Mexico and Argentina. In the U.S. Blockbuster Video refused to carry the title when it hit VHS the next year costing the studio millions in profit.

Its a shame so many refused to see it (and greater shame, tried to prevent general audiences from seeing it) as The Last Temptation of Christ is not only one of my favorite Scorsese movies, it is one of my ten favorite movies of all time. The movie was virtually ignored at Oscar time in 1989, but that would change with his next movie.

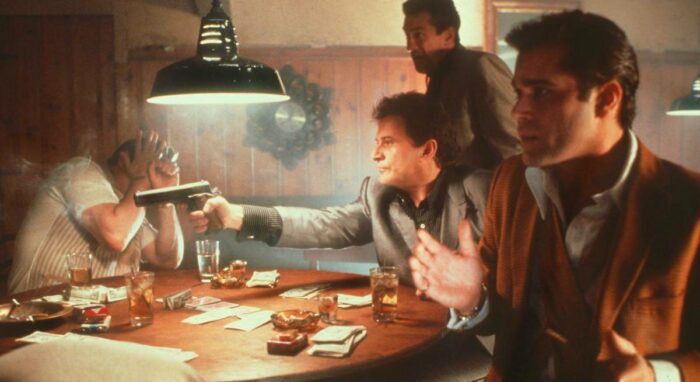

Goodfellas (1990)

The fall of 1990 was known as the season of the gangster as Goodfellas, Miller’s Crossing and The Godfather Part III all opened within months of each other. Miller’s Crossing earned some respectability (but no box-office) and The Godfather Part III earned (very undeserved) scorn upon its release. When Goodfellas finally hit VHS in June of 1991 (nine months after its theatrical run), video stores could hardly keep it in stock. It was the summer rental of 1991 (Blockbuster had no problems with this movie that year). From there, its legend grew and Goodfellas is considered to be the greatest mob movie ever made.

Based on the true-life story of “wise guy” Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), Goodfellas takes place over the course of two decades in a small mafia family. Their biggest score depicted was a heist of a Lufthansa vault at John F. Kennedy International Airport in December 1978 where around $5 million was stolen. When the police began closing in, members of the “family” started showing up dead and Hill decided to turn state’s witness against boss Jimmy Conway (De Niro) or he knows he’s next to wind up in a freezer or “in the weeds with two in back of the head.”

Goodfellas is paced like a bullet from a gun. It goes from one memorable, powerhouse scene to the next and every second is enthralling. Ever watch a movie where you can feel your heartbeat increasing as it goes along? Goodfellas is that kind of movie and what’s even more remarkable, its action is in its dialogue—not in shootouts and chases. Yes, there are shotgun blasts but in this world, they’re over before anyone even realizes what just happened—especially the victims (poor, Spider).

Goodfellas did well at the box-office and critics were ecstatic for the movie but at Oscar time it only won for Joe Pesci’s now legendary performance. In the end, it was neither Miller’s Crossing nor the third Godfather picture which would win the major awards—they went to Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves. But Goodfellas made an even bigger impact. It’s one of the best-selling DVDs ever, and a few years later, was cited as a major influence by David Chase (“Goodfellas is the Quran for me,”) for HBO’s The Sopranos.

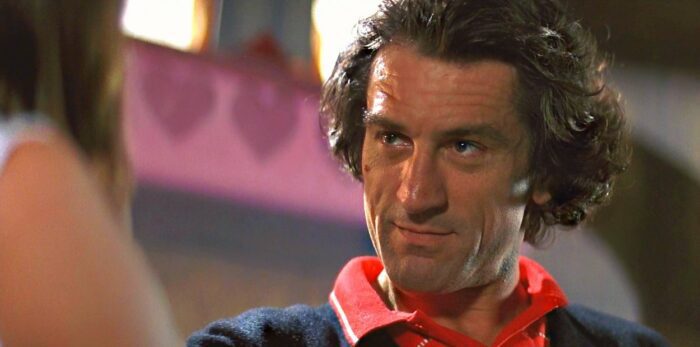

Cape Fear (1991)

Cape Fear had the unfortunate fate of being released nine months after The Silence of The Lambs in 1991. Also, the video of Lambs had been released a month before Cape Fear hit theaters but as I’ve held firm ever since, for my money, Cape Fear is by far the scariest of the two. No movie has frightened me as much as Scorsese’s exploration of revenge, psychological warfare and sadistic torment.

Originally, Cape Fear was going to be made by Steven Spielberg (with a happy family as the focus) and Scorsese was going to make Schindler’s List as his next project. The two friends swapped scripts and you could say it worked out better for them both.

The story is not complicated: newly released felon Max Cady (Robert De Niro) seeks out the defense attorney, Max Bowden (Nick Nolte), who failed to keep him out of prison fourteen years prior for a vicious sexual assault against a woman. Cady’s intent is to terrorize the life of the attorney as a form of payback. Cady doesn’t want to kill Bowden—he just wants Bowden to think Cady wants to kill him. Cady’s weapon is fear and he’s a master at instilling it.

Cape Fear’s most unsettling scene occurs when Max corners Bowden’s teenage daughter, Danielle (Juliette Lewis) in a school auditorium. It’s hard to know which parts of this scene were scripted and which were improvised but the actress blushes as Max approaches her and proceeds to suck his thumb. Max then goes in for a deep kiss—one where her innocence is taken right before our eyes. When the scene is over, we know Danielle will never be the same and neither will we.

Cady’s obsession burns with furious rage and there is no let up from his single-minded mission to terrorize this family. Scorsese once more explored the themes of guilt, sin, obsession and violence here. If The Last Temptation was his exploration of the divinity of Christ, Cape Fear is his examination of Satan from hell, living among us in the flesh.

It’s tremendously powerful stuff.

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Three hour Scorsese movies about greedy, lustful criminals who throw money away the way the rest of us throw away napkins (as Henry Hill put it, the “schmucks” who worried about bills and working 9–5 jobs) wasn’t particularly new ground for the filmmaker. He had done it in Goodfellas and Casino, where the name of the game was ‘show us the green or you’ll be spurting red’ but for The Wolf of Wall Street, it was only about the green. There’s not a single drop of blood anywhere in this epic and one even comes away believing that if these guys were to even see a drop of blood, they’d pass out on their beds stacked entirely out of thousands of dollar bills next to their supermodel wives.

The Wolf of Wall Street was based on Jordon Belfort’s (played by a marvelously comedic Leonardo DiCaprio) book, a true story about his years as a Wall Street stock broker, and how ultimately the FBI arrested him for embezzlement and again, a second time, for breach. The Wall-Streeters depicted here living in their $1.2 million mansions on Long Island may seem the furthest thing from Scorsese’s Little Italy wise guys living in their modest homes, but there are many similarities: the gluttony, the penchant for crime and rule-breaking, the women on the side, the use of four-letter words (506 uses of the f-word here. Imagine how many there were in Scorsese’s four-hour cut) and the reckless thrill of pulling it all off.

The Wolf of Wall Street was faster-paced than 1995’s Casino but isn’t quite the adrenaline rush Goodfellas was. It is much lighter in spirit (there are no overtly powerful dramatic moments) and the dialogue is near Aaron Sorkin-esque in its rapid fire delivery. Not a surprise as this movie was written by Terence Winter, the gifted writer behind some of The Sopranos best episodes.

And who says Scorsese couldn’t do comedy? The scene where Belfort attempts to get into his car while high on decades-old quaaludes is as hilarious as anything Gene Wilder or Steve Martin has ever done on film. When he gets home to find an equally out-of-it Donnie (an excellent Jonah Hill), the two fight each other with a phone cord while Jordan’s wife (in a knockout performance by Margot Robbie) intervenes while the cartoon sounds of Looney Tunes and Popeye on the TV perfectly sync to the visual lunacy.

It paid off as Wolf of Wall Street became Scorsese’s highest-grossing hit ($385 million). It’s safe to say that Scorsese, after his doubts ten years into his career, is no longer an outsider. He is, besides his good friend Steven Spielberg, cinema’s greatest storyteller.