With life slowly starting to return to “normal” after the COVID pandemic, 2022 might for many be the first full year in the last three when cinemas are reopened. With long delayed movies like Top Gun: Maverick finally releasing and distributors seemingly deciding what goes to streaming and what to theatres on a roulette wheel, it’s been a typically oddball six months for cinema. Of course Marvel are still holding strong, although the discourse around each of their six million new releases has never felt more fractious or uneasy, with lukewarm receptions and combative discourse arising due to challenges from more offbeat underdogs like Everything Everywhere All at Once. It’s an interesting time for cinema which feels less predictable now than at any time in recent memory, with many of the most hyped releases feeling eminently disposable and great movies coming from places you’d never have known to look. When asked to provide a lineup of their absolute favourite movies of the year so far, Film Obsessive’s reviewing team Hal Kitchen, Don Shanahan, Tina Kakadelis and J Paul Johnson came through with such an eclectic assortment of choices that there was hardly any overlap between our lists at all!

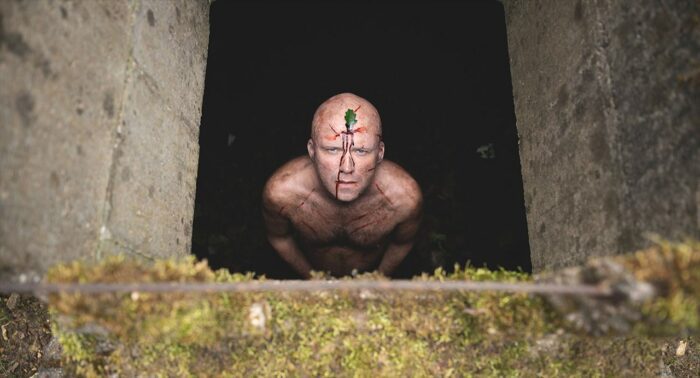

Men

One of the more polarising films of the year – and there’s been a few already – Alex Garland’s film Men did little to hide its obvious thematic intentions from it’s very title. Much of the criticism it has received has been founded on either it being too obviously allegorical or just falling apart into abstraction. Aside from these two criticisms being in opposition to one another, I don’t think either one is true. All the way to the end, Men is pretty blunt with what it’s about, as have all Garland’s films thus far been. And the argument that it doesn’t work as a horror because it’s too self-aware, that does have a little merit, I’ve felt that way about many similar horrors of late, but it was never an issue I had with Men.

From the stunningly rich and vivid visual style and haunting soundscape provided by Geoff Barrow and Ben Salisbury, Men is an absolute treat for the senses, alternating moments of exquisite beauty with those of esoteric grotesque and delicious gore. As protagonist Harper (a career-best Jessie Buckley) is forced to confront the anxieties and fears invoked by the male gaze (embodied by a revelatory, scenery-chewing Rory Kinnear), her world sinks into a spiral of surreal torments, bringing her face to face with each of the many faces of masculine entitlement. And God is it fun! Maybe it’s not too scary or subtle, but it’s decadently exhilarating, visceral, imaginative, and thoroughly ruthless in its macabre carnival of profane wanderings. Far from being a sadistic cavalcade of feminine suffering, it’s an exquisitely cathartic, darkly funny and beautifully nasty, no-holds-barred evisceration of patriarchy, male insecurities and unchecked neuroses that left me grinning the whole way home. — Hal Kitchen

Boiling Point

I’ve often bridled against the strategy employed by some movies of depicting events through a single, unbroken shot. It’s undeniably impressive when done, though it’s rare that the entirety of a narrative’s duration is always equally well served through the same style of camerawork, with nearly all such films feeling as if they could’ve done with more shot variety, and many of the most high profile such films ‘cheating’ the strategy, concealing edits through sleight of hand or VFX, seemingly admitting that the potential of a single take isn’t as great as the film would seem to have you believe.

I do still have a tremendous amount of respect for those films that can pull off the strategy though. It often feels more like an immersive piece of visual theatre than a film, requiring the cast to deliver their scenes in an unbroken chronology, but it’s actually far more in depth than that, cause the level of reality remains the same as any other film, and still competes on the same level of realism expected of the medium, unlike theatre. To complete Boiling Point, a film set in a working kitchen over the course of a single evening, the production not only had to stage a live performance of a real time stage drama, but it had to share the same space as a film set, which had to remain invisible at all times, while the actors all replicate the experience of a chaotic and stressful kitchen environment. Either task would require an enormous amount of coordination and people managing to pull off, to do so simultaneously, is a breathtaking achievement.

But, nearly all films require a similar level of planning and finessed execution. Boiling Point isn’t the only film to pull it off without cutting corners and that stunt alone wouldn’t put Boiling Point on this list. What does that is that Boiling Point is the most exhilarating and tightly wound drama in recent memory, with naturalistic but pulse-racingly intense performances and a tautly composed script that evocatively sketches a huge core cast of innately believable characters undergoing one dramatic peak after another. It’s a breathtakingly powerful piece of drama, staged with immaculate performances and a sense of realism and keen observation that sinks the movie’s hooks deep into the viewer. The only reservation I have in recommending it is the trigger warning for anyone who has ever worked in hospitality themselves! — Hal Kitchen

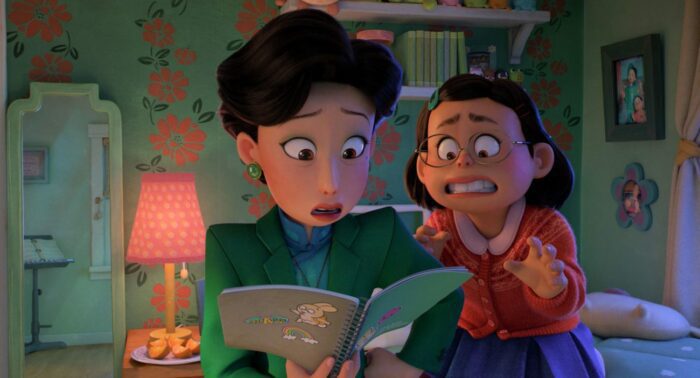

Turning Red

What an unexpected delight Turning Red was. I shouldn’t have been surprised at how brilliant it is, but I was. Pixar had been on an unbelievable hot streak in recent years, with Toy Story 4, Soul and Luca all making my end of year top ten (I even loved Onward, which seems to have gone by the wayside). They seem to have hit on a winning strategy, handing the reins onto a younger generation of directors like Domee Shi and Enrico Casarosa, for them to tell personal, funny and exuberant stories about kids being kids. Turning Red may have raised eyebrows, but for very, very dumb reasons, none of which should prohibit you, or your child, from viewing one of the smartest, funniest and most wholesome family movies around.

Director Domee Shi returns to the generational divide she explored in her Oscar winning short film Bao, but this time from the child’s perspective, bridling against a strict, clingy mother. This has been a heck of a year for Western fantasy adventures allegorising the drama between exilic/diaspora Chinese mothers and daughters. As magnificent as Everything Everywhere All at Once is, it’s hard to deny that this offers a much tidier and more succinct emotional journey. I wouldn’t know if the films recreation of an early ’00s Toronto is accurate, but it’s definitely enviable, with radiant colours, great bubblegum pop courtesy of Billie Eilish and Finneas, and one of the most believable and funny teen girl-groups ever put to screen for company!

The way the film navigates its themes of coming of age and intergenerational conflict is masterful, fully acknowledging the myriad of nuanced influences that go into constructing this cultural pattern, and I especially love the way young Meilin-Lee’s breaking out of it is framed as her embracing her Chinese ancestry and heritage, not rejecting it. It’s just so beautifully accepting and celebratory, with grounded emotional stakes, hilarious gags and such a fun, feminine and vivacious attitude and aesthetic. Turning Red is an utter delight from beginning to end. — Hal Kitchen

The Northman

With full admission as the press-credentialed film critic of the bunch, I don’t know how to describe or process Robert Eggers and his M.O. As striking as his films are in aesthetics and boldness, my emotional strains always seem to stay as cold as the movies themselves. In all honesty, I’m the kind of guy that thought The Lighthouse was boring and not f–ked up enough to really resonate. I’ll grant that I could be missing the proper intent, but to see Eggers take on something bigger and more mythic like The Northman cured many of my doubts and stumps of bias.

The Northman was like Eggers pounding my fears and feelings with a hammer instead of poking them with needles for two hours, and I couldn’t have been more accepting of that greater wringer. His film potently brewed Norse mythology and ethereal pagan oddity into a simmering cauldron that is pungent anywhere you look or listen. Across the top cast, from lead actor Alexander Skarsgard’s stalking deposed heir to Nicole Kidman’s blackhearted noble matron, animalistic urges press against heady Shakespearean precursors in a revenge film that always has something more heavy and portending going on than mere bloodlust. Nonetheless, the brutality is not squelched between the monologues.

So many artistic elements seize you from the start and jolt your reactions and sensibilities. Using a heap of natural light, raw production designs, and exotic filming locations, The Northman might as well depict another planet from our cultured places of today. The landscape is bigger and therefore inescapable compared to his more isolated previous films. The Northman counts as a proper escalation of what an artist and storyteller like Eggers can do with a bigger budget and thicker material. Maybe he had to rein some of his manic tendencies for a larger distributor, but maybe his bigger handlers also amplified the best of what was always there with him. — Don Shanahan

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On

As a school teacher and father of elementary-age children, I’m always on the hunt for films that have some worthier-than-normal substance for kids. Call it my film critics scruples invading my search, but the likes of another Minions movie isn’t good enough for this parent. We don’t give the child demographic full enough credit to absorb something abstract. In my experiences at home and at school, they can do it when given the right material and opportunity. That’s where Marcel the Shell With Shoes On comes in.

Voiced by Jenny Slate and expanded from the YouTube stories created by director Dean Fleischer-Camp, Marcel the Shell With Shoes On takes a hokey premise requiring disbelief and uses it to open doors to new optics and new feelings for viewers. That charming little one-eyed carapace speaks his mind on the intricacies of home and the dynamics of community. If only more kids could see, think, and dream like this diminutive castaway.

The movie combines a sly blend of new school and old school. Calm cinematography and patient storytelling chimes in with a pleasant refresh rate matching a PBS/Bob Ross level, compared to the usual hyperactive content of today. With its natural restraint, Marcel the Shell With Shoes On presents an offbeat story with enough modern setting ingredients to still connect to the current digitally-native generation.

When a movie can do that with charm and feels, we’ve finally found something special.Wearing my “dad” shirt and my film critic hat, Marcel and the Shell With Shoes On is the kind of affecting and less-obnoxious movie we should be showing our kids these days on a regular basis. Let them hold still and squint to appreciate a world smaller than theirs and an askew worldview beyond their own. — Don Shanahan

Good Luck to You, Leo Grande

“Brave” is a word that gets overused anytime a film actress, young or old, takes on a role that steps out of a lady’s expected lane of decency, daintiness, and beauty. That word is everywhere I look when I read or listen to folks talk about Emma Thompson in Good Luck to You, Leo Grande. With no clarification, “brave” then becomes a nondescript word that wears itself out. It certainly isn’t enough of a word of praise to describe what she’s doing in that film directed by Sophia Hyde and written by Katy Brand.

At some point, the bravery should be clarified as honesty and truth to broach subjects people are fearful of handling. Streaming on Hulu, Good Luck to You, Leo Grande offers an almost single-setting morality play that has the courage to empathize with both the sex worker and the client. Anyone who thinks this dramedy is a flippant excuse for another “hooker with a heart of gold” story like Pretty Woman or some carnal venture to admire bodies for kicks is missing the more fragile larger picture.

Emma Thompson and her wonderful co-star Daryl McCormack put the frankness forward to bust taboos and open doors to the closed-off emotions that come with the pursuit and fulfillment of intimacy, especially at an advanced age. The multitude of raw, shared conversations of confidence given and confidence received between the two performers are brilliantly acted. The soul-baring talks are the spicy things to see and they take their time to present the dire needs that put these two people together. Both Thompson and McCormack deserve serious awards consideration at the end of the year. Let’s see the Academy be the brave ones for a change. — Don Shanahan

Cha Cha Real Smooth

Cha Cha Real Smooth is the second film from writer/director Cooper Raiff. He made a name for himself in the indie world with 2020’s Shithouse. At only 25 years old, Raiff is proving to be one of the most important voices of Gen Z.

Andrew (Raiff) is a recent graduate from Tulane University who moves back in with his parents (Leslie Mann and Brad Garrett) and younger brother David (Evan Assante). He’s at a loss of what direction to take his life in and that indecision is compounded when his girlfriend (Amara Pedroso Saquel) leaves him to go to Barcelona to finish her Fulbright. Andrew’s life of working his boring food service job and schlepping his younger brother to mitzvah pales in comparison to the expectations he had after graduating.

At one of David’s classmate’s bar mitzvahs, Andrew comes to realize that he has a talent for being a party starter and opens his own business. Andrew meets Domino (Dakota Johnson), a young mother, and her daughter, Lola (Vanessa Burghardt). Domino and Lola take a liking to Andrew and his sincere kindness. The three start to spend more time together and Andrew begins to fall for Domino.

What sets Raiff’s apart is his earnest dedication to sentimentality. His characters lead with a gentle kindness despite not fully understanding one another. It’s a lesson we all could stand to learn. Perhaps Raiff is able to capture the youthful restlessness, indecision, and ambition so perfectly because he’s experiencing those same early-twenties emotions at this very moment.

Cha Cha Real Smooth is honest. A true heart-on-the-sleeve work by Raiff, an incredible introduction to Burghardt, and a career-defining performance by Johnson. — Tina Kakadelis

Everything Everywhere All at Once

Despite being a movie that spans the multiverse, Everything Everywhere All At Once is a very simple film. It’s a family drama about not understanding one another, the disconnect between generations, and the effort that goes into loving someone.

Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh) and her husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan) run a struggling laundromat that is being audited by the IRS. On the day of their meeting with IRS inspector Deirdre (Jamie Lee Curtis), Evelyn’s father (James Hong) comes to town. Adding to the stress of the day, Evelyn and Waymond’s daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), believes today is the best time to introduce her grandfather to her girlfriend (Tallie Medel).

In the midst of the meeting with Deirdre, a version of Waymond appears from another dimension arrives to informs Evelyn that the multiverse is falling apart. There’s a great evil darkness spreading across all the universes and only Evelyn has the power to stop it. Her heroic journey takes Evelyn through a universe where she’s a famous actor, one where everyone has hot dogs for fingers, and another where a restaurant chef (Harry Shum Jr.) is puppeted by a raccoon.

The absurdity of the circumstances and universes Evelyn finds herself in are exaggerated, but life doesn’t exist without absurdism. Everything Everywhere All At Once is focused on the relationship of a mother and her daughter. The film touches on themes of nihilism, mental health, and the “what ifs” of life. At its core, though, the film is a celebration of life and the people we share it with. It’s paralyzing sometimes to look for meaning in what feels like a meaningless world sometimes, but it’s the people who make existence something special.

“You are useless alone. Good thing you’re not alone,” says Evelyn toward the end of the movie. Hopefully, you find the people who make you not alone. — Tina Kakadelis

Top Gun Maverick

It’s easy to roll your eyes at the idea of returning to the same characters 36 years after the original film premiered. In fact, there are many recent examples warning filmmakers against doing exactly that. Mining nostalgia for the sake of a quick buck rarely works as something beyond sentimentality. Top Gun: Maverick is the exception that proves the rule.

Tom Cruise returns as the titular Maverick. While he still maintains some of the ego from the original Top Gun, there’s a sadness in him now. He’s been surrounded by loss and forced to reckon with the fact that his days flying with the Navy are numbered. When tasked to train a group of recruits to fly a dangerous mission, Maverick understands what’s at stake better than he did when he was in Top Gun class. He’s still haunted by the loss of his best friend Goose (Anthony Edwards) and is forced to face his past when he realizes one of his students is Goose’s son (Miles Teller).

Top Gun: Maverick goes beyond being a high-octane summer blockbuster, though it does provide some of the most edge-of-your-seat flying sequences to ever be captured on film. The film also has Cruise’s best acting performance in recent memory and potentially in his entire career. Like Maverick, Cruise is growing older and there will come a day when he won’t be able to jump out of planes or climb skyscrapers for whatever action movie he’s filming. Where does that leave him? Who is he without the part of his life that has become his entire identity?

With more heart than its predecessor, Top Gun: Maverick will make a fan out of any nonbeliever. The addition of an exciting group of young actors and the film’s ability to pay homage to its roots makes Top Gun: Maverick a true standout. — Tina Kakadelis

The Duke

My preferences tend to run to the offbeat, but I am more than anything moved by films that touch the heart and engage the mind. Celebrated director Roger Michell’s last film, The Duke, is set in historical fact. But it’s not a morbid docudrama or biopic. Instead, it’s a savvy heist caper with a beating heart, brilliantly conceived and perfectly executed. Jim Broadbent plays Kempton Bunton, a 60-year-old taxi driver, unpublished playwright, outspoken advocate for the elderly—and suspected art thief—in what may turn out to be a career-best performance in an already-marvelous career.

In 1961, England was shocked theft of the famous Goya portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in London. It was and still is the only theft in the Gallery’s history! Bunton sent ransom notes for the painting, asking for better care for pensioners in exchange, and later confessed to the crime. The theft and subsequent trial—where the film begins before its flashbacks—are the stuff of British legend. This is The Duke’s simple story, but the truth of the matter is far deeper.

And more satisfying. Handsomely shot, tightly edited, and cleverly scored, The Duke borrows just enough of the quick-cut style of the caper film to jostle the plot along. But Broadbent and co-star Helen Mirren as his suffering, supporting wife Dorothy are given plenty of space too to work their veteran magic. Even more surprisingly, Michell makes this scenario—one as old as its protagonist!—relevant to our pandemic age. Far more than a well-crafted, well-acted period piece, The Duke is a rousing, crowd-pleasing, stunner of a film with a plenty of secrets and surprises, a film that knows the heart is more important than the heist. — J Paul Johnson

Mad God

What is animation if anything but bringing the inanimate to life? And what does that make its creator? A “Mad God,” perhaps?

If I confess to something of a sucker for the cinematically offbeat, Mad God is my catnip. In 1987, legendary visual effects artist Phil Tippett (The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, Robocop, Starship Troopers, Jurassic Park, and more), began fabricating the inhabitants of a nightmarish surreal world with dozens of environments and hundreds of puppets based on thousands of sketches and storyboards. And then, sadly, abandoned them in storage, where they sat, dormant, like lifeless victims of some unseen apocalyptic event.

It was decades before a group of animators rediscovered them. Fortunately, they and Tippett worked together, found funding, and created the weird world of Mad God, a fully practical stop-motion classic of bizarre monsters and mad scientists. The film does not follow, and need not follow, any conventional narrative paradigm. Instead it focuses on Tippett’s vision of a nightmarish world teeming with bizarre creatures. Featureless effigies toil at Sisyphean tasks. Monstrosities ooze pus from unfathomable orifices, poke and prod with crustacean claws, sport spikes and horns like semi-prehistoric dinosaurs, or spout bulbous growths and festering boils. Danger abounds everywhere.

Only the very slimmest of narrative threads stitches together separate sequences, so Mad God is a film to be experienced, not so much followed. And it might feel a little too close to home to those whose recent experience with our own world has felt traumatic, perhaps even near-apocalyptic. But more than any film I’ve seen in recent memory, Mad God creates a visual dystopia, a hellscape if you will, one that is completely convincing and immersive, even in its old-school steampunkish approach to stop-motion animation. The film is clearly a labor of love and a brilliant vision brought finally, after decades, to the life it deserves. — J Paul Johnson

The Tale of King Crab

Even stranger in its own way than Mad God is The Tale of King Crab, a film whose narrative is every bit as strange as its origins, but no less effective for its being so. What’s a good story, after all, without a little imaginative excess?

For a decade or so, Italian co-director-writers Alessio Rigo de Righi and Matteo Zoppis have filmed their discussions with local Vejanos, resulting in two nonfiction films: Belva Nera and Il Solengo. In The Tale of King Crab their collaborations have yielded a third film, one that is fictional, fantastical, and yet simultaneously rooted in the loose, weird reality of local legend.

Debuting at Cannes last year and finding its way to broader theatrical release in 2022, The Tale of King Crab offers a tale, indeed, one told in an Italian village, and a king crab. Its quirky, mysterious, title only hints at the rich, complex narrative that unfolds in two parts. In the first, titled “The Saint Orsio Misdeed,” Luciano (Gabriele Silli), an outcast known as lover, saint, drunk, and even murderer, wanders a remote village in Tuscia. Bad blood between him and the region’s prince leads to regrettable consequences for the woman he loves, and his subsequent vendetta against the prince ends in spectacular failure. The second chapter takes Luciano to “The Asshole of the World”—far asea to the Patagonian region of Argentina, where he is exiled for his crimes.

Throughout, Gabriele Silli, a performance artist, is mesmerizing as Luciano, protagonist of legend whose exploits register more than a century later. His piercing blue eyes dart through an unkempt mop of gnarly hair and mottled beard, weeks’ worth of dust and dirt creasing the lines of his face. The band of village elders are nonprofessional actors, too, and the source of the story told to co-writer-directors de Righi and Zoppis. The film evolved towards its fictional, mythical approach as they worked with the local storytellers to flesh out the legend with cinematic detail.

Enchanting and upsetting, oblique and creative, tender and touching, The Tale of King Crab bodes well for filmmaking that willingly, brashly breaks down locked gates and pursues its passions. In an era of franchises, blockbusters, adaptations, and sequels, The Tale of King Crab stands out as a film that bears its arthouse influences (Bunuel, Jodorowsky, Bergman, Fellini, Herzog, Antonioni) yet is ultimately unlike anything else. — J Paul Johnson