Given the direction the Mission: Impossible franchise has taken over the last twenty two years, all the way through to the most recent sixth outing Fallout, it is easy to forget Brian De Palma’s original, but just as easy to underestimate quite how skillfully it launched one of Hollywood’s most impressively consistent franchises.

Mission: Impossible happened just before cinema began to change. It happened just before the post-modernist transformation of Hollywood into a self-referential field of franchises that would go on to metaphorically eat themselves, in the wake of Wes Craven’s Scream and a thousand imitators. It happened in advance of the rise of the blockbuster which did not rely on the tentpole, marquee name to keep afloat, as The Matrix sequels gave way to the first flourish of the comic-book movie rise across the 2000s. It happened in the midst of the trend of classic properties being revisited, updated and ‘reimagined,’ properties that began dominating the landscape, arriving in the wake of successes such as The Fugitive. Mission: Impossible, quite remarkably for a picture which is now a quarter of a century old, feels as a result both uniquely rooted in the 1990s and decidedly out of time.

Tom Cruise swiftly became attached to the revival of Bruce Geller’s beloved 1960s espionage TV series having been a life-long fan of the series’ brand of escapism, but Mission: Impossible is far from an honourable adaptation of the source material. Being in the middle of a bridge between marquee name action cinema and the franchise-led blockbuster, De Palma’s picture first and foremost is about the journey of Cruise’s Ethan Hunt, the only member of the Impossible Missions Force who after a mission goes catastrophically wrong in Prague to prevent the theft of the NOC List—which would expose all undercover CIA agents across the globe—ends up the only member of his team in this case not “caught or killed,” as the classic mission briefing states, carried over from the original 60’s show.

It is interesting from the outset that Cruise does not reimagine himself as one of the original series characters for the modern cinematic age—players such as Barney Collier (who admittedly was black) or Rollin Hand. The only connective tissue to the original adventures of the IMF turns out to be Jon Voight’s Jim Phelps, the team leader of a unit which, from the outset, appears to be a long-standing, well-oiled machine. These people are clearly friends and, in the case of Emilio Estevez’s Jack Harmon & Kristin Scott-Thomas’ Sarah Davies, are on the verge of becoming something more. De Palma’s film establishes a team which could have been copied over from the original series, or indeed the idea that this could be the *original* Jim Phelps, having matured into a middle-aged operative who created an entire new team around him.

The idea of Mission: Impossible’s reboot working as a movie sequel was quickly disabused when the original Phelps, Peter Graves, declined the chance to reprise his role for De Palma’s film. His reasons certainly were not about being done with the character; as recently as the late 1980’s, he had been front and centre in a revival of the original series which had been off the air since the mid-1970’s. Graves rejected De Palma’s film, and thereby the chance to tether Phelps and the film to the original series; not just because De Palma chose to implode the idea of the IMF team itself, but to have the previously inviolate bastion of all-American espionage, Phelps, turn out to be the villain of the piece.

This incensed not just Graves but the original Collier, Greg Morris (who walked out of a screening before the end) and the original Hand, Martin Landau, who spoke about his concerns which predate even the script which De Palma ended up filming:

When they were working on an early incarnation of the first one – not the script they ultimately did – they wanted the entire team to be destroyed, done away with one at a time, and I was against that,” he said. “It was basically an action-adventure movie and not ‘Mission.’ ‘Mission’ was a mind game. The ideal mission was getting in and getting out without anyone ever knowing we were there. So the whole texture changed. Why volunteer to essentially have our characters commit suicide? I passed on it. I said, ‘It’s crazy to do this.’ Why revisit something that stands for itself?

This betrays a little naivety from Landau about how Hollywood recycles what it considers to be a success, but it certainly touches on a key question about Mission: Impossible which does bear considering: why did Cruise, his first-time producing partner Paula Wagner, a multitude of screenwriters including Steven Zaillian, David Koepp & Robert Towne, and ultimately Brian De Palma, choose to destroy the very fabric of, what on the face of it, made Mission: Impossible *Mission: Impossible*? Because if you watch the film, and compare it with the TV series, they are without a doubt different beasts.

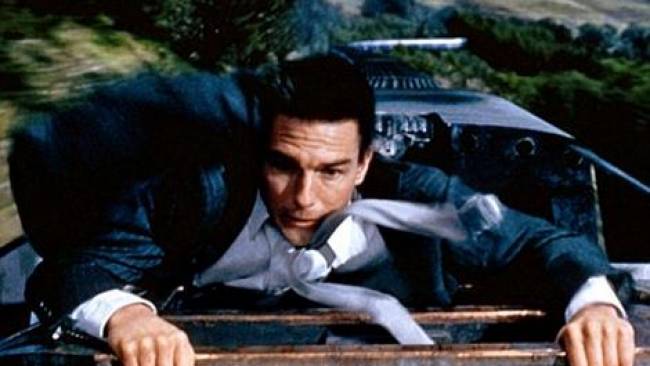

De Palma nevertheless fools you into believing it might be a faithful adaptation with his first act, following the opening sequence whereby Phelps, Hunt and the IMF team use a range of theatrics, from the infamous masks which would become a staple of the entire ensuing franchise, through to a con job using sets, performances and disguises, in order to get what they need from a target. The sixth film, Fallout, pays homage to this in a similar sequence before its own credit sequence, but the difference here is that the audience are in on the performance, with De Palma giving us what we expect from Mission: Impossible: teamwork, staging and illusion. The credits, which recall the original series too with a reworking of Lalo Schiffrin’s iconic theme and flashes of the mission to come, reinforce De Palma’s own illusion. The longer con is on the audience themselves.

Hence why when De Palma, by the end of the first act, kills almost the entirety of the IMF team—including seemingly Phelps himself—during a mission everyone expects them to succeed in as part of the greater challenge, you are left reeling. This has to be part of the illusion of the narrative, surely? The IMF team can’t all be dead? The clue is in casting Cruise, whose shelf-life as a global cinematic superstar is perhaps one of the most durable in Hollywood history. Cruise is entering his *fifth decade* as a leading man. Just let that sink in a moment. By the mid-90’s, he was very much established thanks to films from Top Gun all the way through to A Few Good Men. Cruise’s name was above the poster. Cruise *was* Mission: Impossible now. This early on, however, we just didn’t know it.

One of the key aspects of the Mission: Impossible franchise is how successfully it has managed to reinvent itself. After a problematic Mission: Impossible II, which attempts to build on Cruise’s star power and transform Hunt into 007, Mission: Impossible III onwards begins a steady full circle back to what De Palma established with Cruise and the Ethan Hunt character, while honouring the evolving cinematic trends of the day. In 1996, however, nobody involved with Mission: Impossible truly understood what they had with Cruise or Ethan. They could not have foreseen how Cruise would end up the rock at the centre of a franchise which would improve steadily over two decades in the eyes of critics and fans, despite sometimes gaps of up to six years between movies. They could not have known Cruise would push the limits of his capability as a stuntman alongside actor, almost to the point of self-parody.

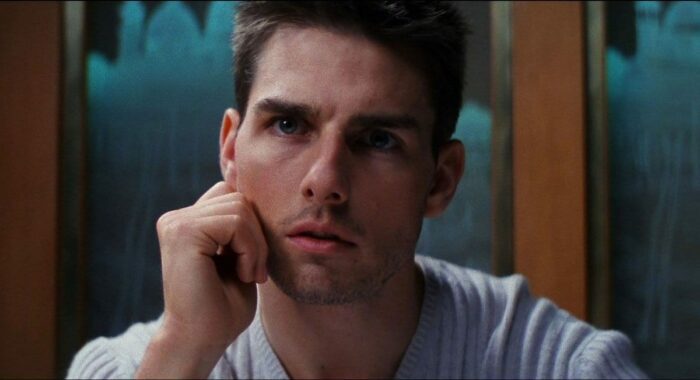

In short, Mission: Impossible does not yet understand Ethan Hunt. It presents a very different character to the one Cruise eventually builds him into. Ethan, here, is the begrudging, vengeful spy betrayed, as far as he is concerned, by his own government after he is fitted up as a mole inside the IMF that the CIA—in the form of Henry Czerny’s delightfully mercurial Kittredge, soon to return in the upcoming seventh and eighth outings—has been looking for. It kickstarts what would become some of Mission: Impossible’s most popular tropes, second only perhaps to the mask disguises: the mole and the disavowal. There is not one MI film which does not either contain a mole working within American intelligence or Ethan’s loyalty and fidelity being questioned. Phelps here, rogue IMF agent Sean Ambrose in MI:2, Musgrave in MI:3, Walker in Fallout or Ethan being forced underground or rogue in Ghost Protocol and Rogue Nation.

This becomes so hard-baked into the DNA of Mission: Impossible, and Ethan as a character, that by the point of Fallout, then steward Christopher McQuarrie is actively using this fact as the basis of villains and enemy agents pushing the US government to question Ethan’s loyalty. Henry Cavill’s Agent Walker sums it up in Fallout: “How many times has Hunt’s government betrayed him, disavowed him, cast him aside? How long before a man like that has had enough?”

All of this began in Mission: Impossible the moment Ethan Hunt loses his team, because even despite characters such as Ving Rhames’ Luther Stickell or Simon Pegg’s Benji Dunn becoming loyal allies over successive films, not one picture in this franchise has Ethan working, truly, as the cog inside a functional unit. Ethan *is* the machine. By the point of Fallout, and after some work particularly in Rogue Nation, he has been completely mythologised as a veritable superhero, an espionage-based Batman equivalent who allows people to sleep safely at night knowing he is risking life and literal limb to stop extremists and terrorists the world over. He steadily evolves into this mythic hero across the next twenty years but here Ethan is simply a disavowed, deep cover spy using every trick in the book to clear his name and expose the real mole.

De Palma’s film is, principally, a deconstruction of what made the 1960s TV series work. That show was created at the height of the Cold War, with American and Soviet tensions providing a backdrop for the kind of television that would take the post-war austerity of the 1950s and frame it in glossier, brighter contexts. Mission: Impossible came from the same Desilu Productions stable as Star Trek, which premiered the year before and as MI portrayed a unit which using trickery and manipulation to overcome the enemy, Star Trek looked forward to a future in which the hostilities of the Cold War would be a thing of the past in a new American, even globally united, frontier. Both shows even share Star Trek breakout star Leonard Nimoy as part of their casts.

Whereas Star Trek permeated and managed a breakthrough toward the tail end of the darker 1970s in the American consciousness, Mission: Impossible struggled to bring its brand of theatrical fancy back to a public who had moved on past the anxieties of the Cold War. Its return in the late 80s, just a couple of years before the end of the century-defining conflict, didn’t last long. By the time De Palma’s big screen adaptation was in production, the Cold War was over. The Russian bear had been put down and, suddenly, American espionage didn’t work in the same way. Despite nasty brush fire wars across the 90s such as Iraq or Kosovo, Mission: Impossible returned in the decade defined by Francis Fukuyama in his book The End of History and the Last Man as the titular ‘end of history’:

It is not necessary that all societies become successful liberal societies, merely that they end their ideological pretensions of representing different and higher forms of human society.

Koepp & Towne’s eventual, credited script reflects this in Jim Phelps. When he is unmasked as the villainous architect of the NOC List theft, Phelps’ rationale is revealed in dialogue he offers freely to Ethan in outlining the mindset of the villain, Job, he is trying to convince Ethan exists: “You think about it Ethan, it was inevitable. No more Cold War. No more secrets you keep from yourself. Answer to no one but yourself. Then you wake up one morning and find out the President is running the country without your permission. The son of a bitch, how dare he? Then you realise, it’s over. You are an obsolete piece of hardware, not worth upgrading, you got a lousy marriage and sixty two grand a year.”

There is quite a lot to unpack here: principally the fact that Phelps’ turn to the dark side, the betrayal of his country and the American values we saw his same character embody in the 1960s, at the height of the conflict against the Soviets, was fuelled by the lack of a defined ‘enemy’ for the intelligence community to fight. The destruction of his team also represents a pre-millennial fear that the enemy could be anywhere, even within, as opposed to the ideological Communist bloc close in our mind’s eye, but in literal terms far from our homeland. Mission: Impossible‘s revival reflects a world filled with shadowy, unknown forces who could strike anywhere, at any time, right at the heart of where we feel safe. It almost prefigures the rise of spontaneous terrorism.

We see this anxiety reflected across spy fiction in the 1990s as a whole, particularly in Mission: Impossible’s closest bedfellow – the James Bond franchise. Unlike MI, that 1960s staple never went away and only grew in the cultural consciousness, mainly because 007 never needed to evolve beyond the kind of superhero that Ethan Hunt would eventually become. Bond in the 90s, however, saw the franchise flirt for the first time with the realities of a post-Cold War landscape.

GoldenEye, released just a year before Mission: Impossible in 1995, shares more than a few commonalities. The villain, Alec Trevelyan, like Phelps starts the picture as a loyal spy fighting the good fight for the ‘good guys’ (in this case MI6); like Phelps, Alec seemingly dies as part of a mission which should have been a success, and Alec has a personal, strong connection to Bond, as Phelps does to Ethan. Like Phelps, Alec is also revealed—a little earlier in GoldenEye—to be the grand architect of a plot to destabilise the very system that created him. Both were ‘Cold Warriors’ who realised they had no place in a world which didn’t need their trade in quite the same way. For both men, in the end, they want to make enough “f*ck you” money out of imploding the world order that, in their eyes, betrayed them, to live like kings.

We even see, in GoldenEye, the character of Bond actively being faced with the reality of existing after the end of the Cold War. His new boss is a woman, reflecting the advancement of gender roles in a very male establishment; a woman who refers to him as a “dinosaur” and a “relic of the Cold War”. Pierce Brosnan’s era quickly skips over this introspection, particularly once Bond defeats his dark reflection in Alec, but Daniel Craig’s successive films very much pick up the baton – even if by then, Bond is questioning his relevance in the post-9/11 landscape rather than the post-Cold War one. Ultimately, Mission: Impossible operates in the same sphere. It is trying to understand its place in a new geopolitical landscape, as well as in the changing trends and emerging post-modern narratives of the 1990’s.

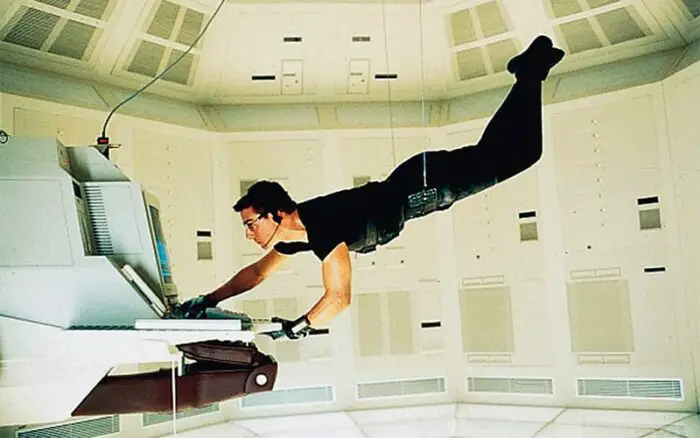

Phelps in his soliloquy also mentions ‘hardware’ and this hints at the emergence of technological means in the post-Cold War paradigm that would replace the need for spies in the field doing the heavy lifting. This is in its infancy in Mission: Impossible, which feels quite charming in watching Vanessa Redgrave’s playful arms dealer Max trying to upload floppy discs onto a computer system before the Channel Tunnel cuts off her connection, but the point remains that intelligence agencies now no longer need men like Phelps. Conversely, De Palma also wonders if they need the IMF, hence why he happily takes down the team thanks to their insider, and leaves Ethan free and clear to create his own ramshackle group of mercenaries to help him clear his name – primarily in the standout CIA Langley set piece, which remains one of the most impressive, iconic and not to mention tense, sequences in action cinema of the last quarter century.

The idea, too, of the NOC List, is one which comes back around in numerous spy stories over the next couple of decades as we move further away from the Cold War, and particularly the new intelligence paradigm of the post-9/11 world. 2012’s fiftieth anniversary Bond movie, Skyfall, essentially replicates this exact same narrative in how techno-terrorist and (again) rogue intelligence operative Raoul Silva steals a list of MI6 covert operatives and prepares to expose them to the world, all part of a personal issue with MI6 boss M. The difference is that Silva has a vast array of server farms and a rampant internet platform to unleash this information on, which Phelps doesn’t have in Mission: Impossible. What he has is a weaponised tool he can sell to the highest bidder in order to destabilise American intelligence interests and threaten to, theoretically, create a new set of Cold War-style conditions in which he can become relevant again.

Though it isn’t really until 2015’s Rogue Nation that Mission: Impossible directly begins to question the validity of the IMF in the modern day—much like Skyfall does with the 00 section—De Palma lays the foundations of exploring whether a concept so rooted in the Cold War showmanship, theatrics and game theory as Mission: Impossible can even exist in a world that doesn’t need it. Rogue Nation’s answer, further underlined in Fallout (which more than any of the previous films attempts to capture some of the essence of De Palma’s movie, even if aesthetically it has more in common with Christopher Nolan), is that the IMF *is* still relevant, but for one reason, and it’s the same reason as with the 00 section: in that franchise’s case, it’s James Bond. In Mission: Impossible’s case, it is Ethan Hunt.

Mission: Impossible does not sell Ethan, however, as a Bond proxy. Cruise’s charm is perfectly evident but Ethan is not a seductive, one-man killing machine, or indeed the death-defying nihilist he becomes post-MI:3. Ethan here is a touch more enigmatic and distant, which befits the colder stylings of De Palma’s approach to the material. His lens channels Hitchcock while imbuing the frame with a distinctly De Palma-level of paranoia. Behind the 90’s action beats and slicker dynamic, there remains a visible 70s conspiracy aspect to Mission: Impossible which is missing from subsequent pictures. It’s as if De Palma didn’t believe in the 60’s show, or didn’t believe it could exist beyond the 60s, and intentionally tries to revive the property within a post-70s culture, one where spooks like Kittredge reflect a government far more willing to sacrifice the lives of spies such as the IMF as part of a bigger, self-interested picture.

You only have to look at the strange character of Claire Phelps to see how Mission: Impossible doesn’t follow a traditional narrative pattern, particularly for a character like Ethan. MI:2, in trying to recast him as an American folk hero spy, immediately gives him ‘the love interest’ who you know will be disposable by the end of the picture (which turns out to be the case), but De Palma never tips Ethan and Claire into any kind of conventional romance. There is sexual chemistry and clear frisson, which almost enters into sexually aggressive territory at one point, but there is only the suggestion that Ethan and Claire may have slept together, and that Ethan may have compromised his own morals in doing so. Yet, in much the way Ethan becomes a tactical master three steps ahead of his enemies, sleeping with Claire may have been part of his plan all along, when ostensibly it seems to be part of Phelps’.

Claire, played by beguiling French beauty Emmanuelle Beart, is a strangely inert character. She is a spy yet does not seem to have any real agency about her. She is married to Jim yet this almost feels like a technicality, given we see almost no sign of warmth or connection between them. She might or might not have been complicit in murdering the IMF team; during the beautifully executed scene in which Phelps reveals his guilt to the audience yet not directly to Ethan, but which can equally be read as Ethan figuring out that Phelps is Job, Ethan actively imagines and then discounts Claire as the one who blew up team member Hannah’s car. If Ethan does have feelings for Claire, this could be his way of refusing to countenance she could be a traitor\killer, and him trying to protect her, but De Palma keeps it ambiguous. We never quite know for sure, come the end, if Claire was always just in it for the money like her husband. She is also never really defined as a rounded character in her own right.

Phelps certainly seems to believe Ethan slept with his wife and made that connection, given how in their final confrontation he quotes the Bible and the well-known passage: “thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife.” This plays into the odd level of religious symbolism which underlines Phelps’ extremism; he presents himself to Max as Job 3:14, which the CIA believe is code for an operation but Ethan figures out is the following Biblical passage: “with kings and counsellors of the earth, who built for themselves places now lying in ruins.”

This suggests Phelps is or was a religious man (and given Voight’s own personal leanings, very possibly a conservative), particularly in how he seems to be using Christian scripture to justify the betrayal of his nation. ‘Building for themselves’ references his own attempts to become a mercenary and profit over the deaths of many of his fellow spies still protecting their country, while the ‘places now lying in ruins’ could be how Phelps considers America: a country he does not recognise following the end of a career-defining hostility. There is a fundamentalist extremism at play here which, oddly, presages how certain Middle Eastern organisations would twist Islam to fit their own self-aggrandising interpretations as we entered the next decade.

Oddly, though, Redgrave’s Max tells Ethan, when posing as Job, that “Job is not given to quoting scripture in his communications” after Ethan does just that, suggesting Phelps is a false prophet. He doesn’t really know or understand the Bible and it could just be another example of his warped psyche when it comes to America as a nation – using the Christian belief system which underpins the land of the free against it. De Palma doesn’t take these religious notions too much further but McQuarrie certainly revisits them twenty years later in Fallout; Ethan again poses as a terrorist underpinned by quasi-religious doctrine when making deals with Max’s daughter, no less. This is no doubt an intentional homage to the first film but it does show how Mission: Impossible casts a long shadow across the rest of its own franchise.

That’s the thing. Mission: Impossible has never quite escaped the revisionist deconstruction of the 1960s tropes from Bruce Geller’s original TV series. The next film didn’t introduce more of the original series characters to work around Ethan, and make him part of the tricksy team effort (even try and make him *into* the virtuous Jim Phelps from the 60s). It didn’t keep Mission: Impossible to a stock formula for the next few sequels. It didn’t try and repeat any narratives from the original show, updated for the post-modern 90s. What it did, as a franchise, was ensure its durability for two decades by changing the fabric of what it could be, veering closer and sometimes further away, from the original 60s aesthetic of the series, and always keeping Tom Cruise front and centre as the beating heart of the modern Mission: Impossible.

The day will come when Cruise, almost sixty years old as of writing, finally realises he’s a bit too old to be flinging himself off the world’s tallest buildings, and that is when Mission: Impossible will evolve again. It may well go back to the original 60s team, to the style, and to the kind of Jim Phelps that Peter Graves and the original cast wanted to see updated for modern audiences. That would, arguably, work better now than it may have done in the 90s, when franchises and old-fashioned ideas were attempting to introspectively understand their own alchemy. Mission: Impossible, over the next five films, realised that alchemy was Tom Cruise, but for the next generation it will be a different magic. We will get there as we head further into the 2020s.

Until we do, however, we should never forget that while Mission: Impossible grew in scope, in stature and in style, the reason it has become one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining and strong franchises started with Brian De Palma’s skewed, almost nihilistic implosion of what Mission: Impossible meant to audiences. The fuse was well and truly lit here and over two decades on, the flame has never quite gone out.