The year 1996 may sound late in the game in the scheme of film history, but it was 25 years ago when, as a teen, I first noticed legitimate movie theater surround sound. Don’t get me wrong. I knew the multiple component systems existed, but I was too young to see events like Jurassic Park on the big screen. Reaching the age of 17, I have to credit 1996’s The Ghost and the Darkness as when this future film critic really appreciated how a movie can envelop you in audio rapture when tuned properly.

Today’s moviegoers have likely never experienced anything less than Dolby Surround 7.1 or the current creme-de-la-creme of Dolby Atmos, both at the movie theater and on their own home theater systems. Imagine having neither in both places. The leap from front-firing monaural and basic stereo sound to the 5.1 Dolby Surround compression—beginning with Batman Returns in 1992—was nothing short of a game-changer, and sound designers like Bruce Stambler of The Ghost and the Darkness were quickly using the system’s capabilities to their creative advantage.

The Ghost and the Darkness wasn’t a superheroic blockbuster or a special effects extravaganza looking to peel the paint off of theater walls with explosions or revving engines; it was a throwback wild adventure movie and a slow burn creature feature unshy to spray R-rated bloodshed. Visually, it patiently cloaks its feline threats for delayed revelation. Aurally, the movie sneaks up on you from all directions with maximized terror.

Filmed predominantly in the Songimvelo Game Reserve in South Africa, The Ghost and the Darkness, directed by Steven Hopkins (Predator 2, Lost in Space), was a fictionalized take on Colonel John Henry Patterson’s 1898 semi-autobiographical account of two man-eating lions terrorizing the construction of a railroad bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya. Patterson, played by Val Kilmer, was the military engineer commissioned to complete the project with haste by his forceful employer Sir Robert Beaumont (Tom Wilkinson in full cad mode). He leaves his pregnant wife (Emily Mortimer) to visit the continent he’s always dreamed of to fulfill this enterprise.

Stamped with coincidence or karma, Patterson’s arrival coincides with the emergence of unusual lion attacks that rack up dozens of casualties among the Western immigrants and subservient multi-ethnic laborers of the architectural undertaking. It’s in these deadly scenes and the coordinated attempts to hunt the titular demonic duo responsible (played mostly by Caesar and Bongo from Ontario’s Bowmanville Zoo), that two-time Oscar-winning screenwriter William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men) crafts the movie’s carnal suspense.

More than anything, the sound is what gets you. For this movie, the tingling menace started with the opening title card coming out of the slow-motion visual of the tall, flaxen savanna grass gyrating with the stern wind. It’s mere seconds into the movie and, I swear to God, sitting in that theater, you thought that grass was tickling the back of your neck. I had never felt that before.

Exponentially more subtle and effective than a horror movie jump scare, that kind of layer of cinematic atmosphere was perfect. Add in the growing suspicions that an apex predator could lurk or leap out at any moment and your nerves are shot multiple times over.

Like a rhythm out of the sport of volleyball, Academy Award-winning American New Wave cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Deer Hunter) would set you up with smooth swoops and dissolves, and the sound would spike you down. Channeled for that newfangled surround sound, Jerry Goldsmith’s soaring score, one from his late-career prime, synced up with the guttural roars and mashing sound effects of teeth and claws entering flesh. As fate would have it, supervising sound editor Bruce Stambler would win the Academy Award for Sound Editing for The Ghost and the Darkness.

The film beat Daylight and Eraser for the golden statuette. It was Stambler’s first and only win after five consecutive nominations in the category (Under Siege, The Fugitive, Clear and Present Danger, Batman Forever). It couldn’t be more deserving, and the praise needs to be spread to supervising foley editor Michael Dressel (American Sniper), sound effects coordinator John Michael Fanaris (They Live), and sound mixer Simon Kaye (The Last of the Mohicans). With this Oscar-gilded seal, The Ghost and the Darkness is something you absolutely have to try out on true surround sound at home, especially since a theatrical re-release for this subpar hit will likely never come. Somebody send me a time machine.

The Ghost and the Darkness was conceived as a star vehicle for Val Kilmer and Michael Douglas, and that is entirely true. Star presences financed and sold pictures, and this movie combined two in the middle of winning streaks. Kilmer was white hot following his double 1995 slams of Batman Forever and Heat while Douglas rode The American President and Disclosure to then-recent peaks.

Likewise, director Stephen Hopkins coming off of the modest and critical success of Blown Away. That 1994 movie made over $50 million on a $28 million budget. Paramount hired him up and doubled his starting coffers. Grossing back $75 million on a $55 million budget against expectations to top $100 million, The Ghost and the Darkness stands as one of those requisite mid-budget studio programmers that were a moderate industry staple for decades. If they hit big, wonderful, but they were built frugal enough to the point where they rarely lost money.

It is a fair point of contention to Hopkins that Val’s supporting co-star, who doesn’t show up until nearly halfway through the movie, nabbed top billing. That, folks, is the bullying power of being a producer. Steven Hopkins fell victim to that pressure, and parts of the finished film, one he has apparently yet to watch, suffered. Douglas would earn $38 million as the bankrolling producer while Kilmer was paid a handsome, yet uneven $6 million. Michael Douglas is a burly boost when he arrives, but, make no mistake, The Ghost and the Darkness is Kilmer’s movie as the stoic man-of-action.

Fading in and out of a weakly attempted Irish accent, the former graduate of The Juilliard School isn’t exactly performing Shakespeare or Twain. This kind of movie wasn’t asking for that depth of drama. Val’s primary job is to be unflappable against contentious rivals and natural fear. He has to look good staring down the barrel of a rifle or into the eyes of threats that step to him. Kilmer was more than accomplished enough to nail that and could have easily held this adventure down by himself.

Instead, enter Oscar-winning producer Michael Douglas at the last minute with his insistence to play the invented character of Charles Remington. Douglas gets to show up, inject a little wide-eyed screwloose zeal, shout orders, growl through platitudes, and ensure his earmarked earnings. A second lead hunter was not present during Colonel Robert Patterson’s documented account of the ordeal. The Irishman was a hero all by himself. If the picky “white savior” crosshairs came to this movie, they would land on Douglas’s mostly unnecessary character over Kilmer’s.

Luckily, none of that poster placement jockeying or ego-filled sword fighting took away from the exciting results of the movie. The proven hit-maker (The Princess Bride) William Goldman pitched this as a combination of Lawrence of Arabia and Jaws. The movie certainly does not ascend to that hallowed level, but The Ghost and the Darkness successfully mined a harrowing true tale and gave it a grand enough cinematic treatment to garner a minor cult following. That welcome longevity always counts as a win.

Best of all, The Ghost and the Darkness amplified a cherished historical mystique that exists to this day. The fateful and finally completed railroad bridge, nicknamed “Man-eater Bridge,” still stands in Tsavo, although it was replaced in 2014. The real draw remains the legend of the feral lions themselves. Their history takes very little selling, yet the movie gladly lathers up the wonder.

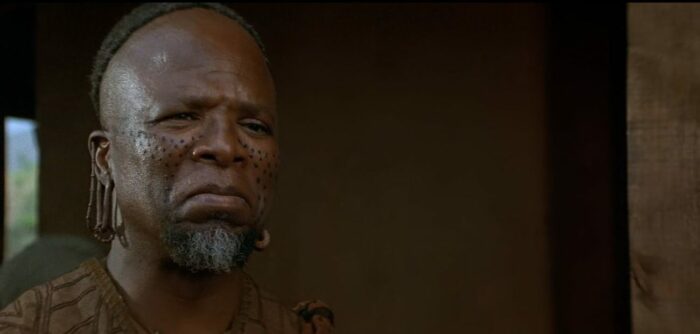

Samuel (future Black Panther patriarch John Kani) opens his narration with the order to remember “Even the most impossible part of this story really happened” out of this “most famous true African adventure.” He concludes the movie and sends us on our way to note that the carcasses of the two lions (resurrected from being carpet trophies) can be visited 123 years later and counting at the Field Museum in Chicago. In a great line, Kani reads, “Even now, if you lock eyes with them, you will be afraid.” As a Chicagoan, I have made that pilgrimage and given that exhibit patronage several times over the years. I can attest that the ending warning is dead right.