As part of 25YL’s Celebration of Women series, we took a look at Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 film La noire de…(Black Girl). La noire de… is a Senegalese film that explores the encounters with displaced identity and diminished autonomy that arise from colonized people’s experiences. Sembène depicts the suffocating repression that occurs in relationships that are defined by cultural domination by exhibiting the alienation and exploitation that a Senegalese woman, Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), endures while working in a white family’s home in France.

Sembène privileges Diouana’s perspective by emphasizing the voiceover of her inner dialogue throughout La noire de… to illustrate her crushing disillusionment and indomitable defiance. Although the film primarily communicates an expression of postcolonial experience, it also bears current relevance to issues of toxic white feminism, self-representation, and intersectionality. As we celebrate female empowerment this July at 25YL, La noire de… serves to edify us on the detrimental quality that hierarchical relationships based on race and class differences can have on the efficacy of feminism as a liberation movement.

I will refer to Sembène’s film using only the French and not the English title, Black Girl. Much of the meaning that the title imparts is lost in the English translation, so I’d like to break down the French so you can get a sense of the film’s overall meaning. “La noire” translates to “the black woman/girl,” and the “de + ellipses” conveys a double entendre. In French, de is a versatile preposition that can mean “of” (objective genitive or possessive), “from” (prepositional), or can describe contents and characteristics. In this way, the title carries open possibilities of meaning, such as “The Black Woman from…” or “The Black Woman belonging to…,” and its ambiguity reflects the destabilizing uncertainty and curtailed autonomy that Diouana experiences.

La noire de… is widely recognized as one of the first Sub-Saharan films to receive international acclaim, and Sembène is often described as the father of African cinema. By extension, many consider Mbissine Thérèse Diop to be the first female lead in African cinema. In a 2015 interview with Film Comment, Diop remembers that there was no other actress that she could compare herself to when filming La noire de…. The film is based on a novella with the same title that was also written by Sembène, who is known for endowing his works with the gravity of political activism. His criticisms of oppressive power structures are grounded in a feminist stance, and he habitually featured women and women’s issues in his films. As an artist, Sembène preferred writing as a form of luxuriant artistic expression. He saw film as a superior method to achieve social change and independence for its potential to galvanize African people, in part because of its visual language and its ability to serve as an extension of African oral traditions.

I consider the cinema to be a means for political action.

–Ousmane Sembène

The film explores several issues that are fundamental to the postcolonial Senegalese—and more broadly, postcolonial African—experience. These thematic issues include displacement, exploitation, fragmented identity, and manipulative deceit. Most essentially, La noire de… serves as an allegorical portrayal of the postcolonial cultural identity of Senegal, with Diouana’s relationship with her employers and her surroundings in France representing the subjective postcolonial identity in microcosm. Central to the film’s commentary on colonial and postcolonial subjugation is a commentary on social absorption in hierarchy, status, and cultural domination.

La noire de… provides an irresolute and disquieting depiction of what is required to achieve liberation from socioeconomically oppressive systems that belies the socially progressive façade of the neoliberal social market economy. Diouana’s tragic fate and the film’s unsettling final sequence provide no easy answers to the problems that La noire de… sets out to address. Reflexively, the ending is as open-ended and shoulders as many dark implications as the film’s ambiguous title.

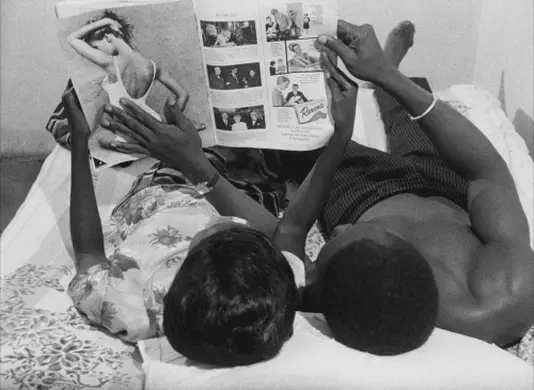

The exposition opens with Diouana arriving in Antibes, France from Dakar, Senegal. She is there to work for her white, French employers who live in Dakar but are vacationing in Antibes. Once she arrives in the Antibes apartment, we do not see her leave it again. As the main narrative of the film progresses, the film cuts back to her memories in Dakar where we learn more about Diouana’s life and how she came to work for the French couple in Antibes. We learn that employment in Dakar is scarce, and that Diouana eventually came to work as a governess for the French couple’s children. We also learn that she had been very excited to go work for them in France, that she dreamed of the new experiences she would have and the identity she might forge in an urbane, cosmopolitan environment.

In Antibes, Diouana finds herself to be the object of intensified exploitation and alienation. Whereas in Dakar the household staff handled various aspects of cooking and cleaning, in Antibes all the household responsibilities fall to Diouana. She soon realizes that she has been brought to Antibes for the sole purpose of being the couple’s maid, and that the wife, Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinck), deliberately misled her into believing she would be able to experience France for herself if she worked for them there. Her independence is entirely restricted because she is prohibited from ever leaving the apartment. The only experience that she ultimately has of France is within this confined space and from the view out her window.

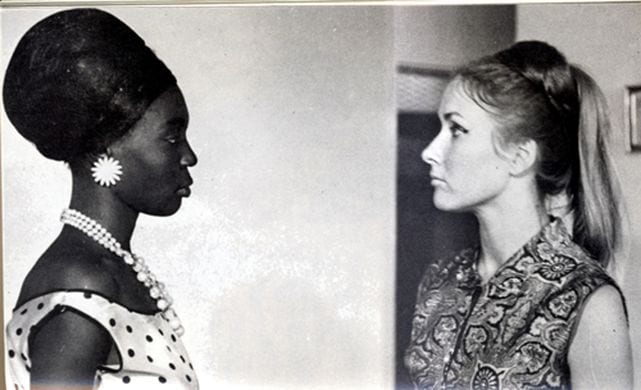

Beyond the slight of being deceived into an exploitation of her labor, Diouana is demeaned even further by Madame who deliberately and openly attempts to degrade her into a submissive social role. For example, Madame insists that Diouana dress like a maid rather than wearing clothes of her own choosing, scathingly condescends to her and humiliates her, and refuses to allow her to enjoy any personal time or personal space. Overall, Madame conveys her belief that Diouana’s very body is her property, disparaging Diouana’s will, identity, and selfhood.

Perceiving that her employers have effectively made her their prisoner and slave, and heartbreakingly disillusioned from her dreams of upward social mobility and personal autonomy, Diouana commits suicide in their bathtub. Before taking her life, Diouana returns the couple’s cash payment for her labor. When the husband, Monsieur (Robert Fontaine), returns her belongings to her family in Dakar, Diouana’s mother also refuses the payment. This refusal of payment by Diouana and her mother communicates a sentiment of defiance and rejection of neoliberal capitalism as a system of modern enslavement.

The filmic style of La noire de… also distinguishes it as a social commentary. Sembène consciously appropriates the film techniques and influential characteristics of major contemporaneous European film movements, namely French New Wave and Italian Neorealism. Adopting the styles of these film movements enabled Sembène to produce an analogous commentary on related thematic elements such as existential angst, the absurdity of life, difficult moral or economic conditions, oppression, and desperation while contextualizing these elements within the postcolonial African experience.

Italian Neorealist films were usually filmed with non-professional actors, and Diop was likewise a seamstress before acting in La noire de…. Similarly, Neorealist films tended to highlight the experiences of the poor and working classes within the context of Italy after German occupation during WWII, and La noire de… also strives to depict the everyday life of poor and working class Senegalese people in the wake of French colonization. French New Wave cinema also is known for engaging with social and political problems, and, like La noire de…, French New Wave films undertook a documentary style to depict these problematic issues. La noire de… skillfully assumes the stylistic devices of French New Wave, including long take shots, discontinuous editing, limited budgets and equipment, and emphasis on the existential individual experience.

Sembène employs the stylistic elements of movements like Italian Neorealism and French New Wave, but he also innovates with a distinct personal style that puts elements of Senegalese culture and African storytelling in conversation with these European filmic techniques. A major example of this originality in La noire de… is the allegorical symbolism carried by the traditional African mask that serves as an undercurrent of the film’s entire meaning. In Dakar, when Diouana is first employed by Madame and Monsieur, she buys the mask from a boy in her village and gifts it to Madame. This act symbolizes Diouana’s faith in the monetized system of cash and labor and expresses her belief that equivalent exchange defines her relationship with her employers.

When she arrives in Antibes, she finds the mask hanging as the sole piece of art on the wall near the entrance of Madame and Monsieur’s apartment, and they have displayed a collection of traditional African masks elsewhere in the apartment. The mask’s placement in the Antibes vacation home disconcerts Diouana. As she eventually learns that her place in their home is one of subjugation and silence, she comes to recognize that the couple’s brandishing the symbol of African culture represents a commandeering of her cultural identity. When Diouana is disenchanted of her belief that her relationship to her employers is one of an exchange among equals, she takes the mask off the wall in an act of reclamation. Madame protests Diouana’s revocation of the mask and physically tries to wrest it from her in an act that symbolizes the climax of her battle for the subjugation of Diouana’s will—in both cases, Madame ultimately loses in her conquest.

After Diouana’s death, Monsieur returns the mask to her village along with the rest of her belongings. The boy who Diouana originally bought the mask from collects the mask, and he wears it as he follows Monsieur out of the village and back to his car. During this long take, Monsieur is visibly unsettled by the haunting vision of Diouana’s mask following him. Perturbed, he consistently looks over his shoulder and hurries his pace, looking stricken as though he is being chased by a ghost. The final scene of La noire de… shows the boy looking directly into the camera as he removes the mask after Monsieur drives away out of the village. The overarching allegory of the mask powerfully illustrates a reclamation of African identity and selfhood after colonization, but still reflects a discomfiting uncertainty about the future. Pointedly, the allegory of the mask acutely implies the ongoing history of colonial European governments displaying stolen African artifacts in museums and refusing to return them after colonization.

Madame’s scornful behavior and her deliberate subjugation of Diouana’s autonomy are driven by an increased preoccupation with her own status in the hierarchy of social power in France. We have already established two major elements of Madame’s domineering relationship to Diouana—her insistent subjugation of Diouana’s personal autonomy and her vaunting of Diouana’s misappropriated cultural identity. There is a third essential element of Madame’s restriction of Diouana’s selfhood that is necessary for Madame’s sociocultural domination over Diouana: Madame and Monsieur enforce Diouana’s voicelessness, which curtails her self-representation in addition to her personal autonomy.

The two primary examples of the denial of Diouana’s self-representation both occur at pivotal moments in the plot of La noire de…. The first is when Madame and Monsieur have French guests over for dinner. Diouana is instructed to cook Senegal-style rice for them, although she internally notes that Madame never eats rice when in Dakar. This flaunting of African cuisine ‘cooked by a real African’ serves as a secondary indicator of Madame’s insensitive cultural appropriation. During the dinner party, one of the guests asks if Diouana can speak French, and Madame briskly replies that she does not. Her lie eliminates the possibility of Diouana conversing with the French guests and deprives Diouana of her ability to speak for herself, effectively completing Madame’s cultural domination of Diouana through exploitation and utter alienation.

The second instance of Diouana’s imposed voicelessness occurs when Monsieur announces that she has received a letter from her mother in Dakar. Because Diouana cannot read or write, Monsieur must read her mother’s letter aloud and write her reply. In the letter that Monsieur reads, Diouana’s mother admonishes her for not sending money back home. Notably, Monsieur begins writing Diouana’s reply to her mother without even consulting her. Because she cannot write, Monsieur should have allowed Diouana to dictate her response for him to record in her own words. Instead, he deprives her of the ability to represent herself to the person with whom she identifies most profoundly. This act becomes the culmination of Diouana’s total stripping of personal agency, and her ability to relate positively to her environment devolves rapidly.

Overall, La noire de… is a film that centralizes not women’s issues but race and class issues. It uniquely privileges the viewpoints and personal experiences of colonized people. Nonetheless, La noire de… enables us to take a critical approach to observing and celebrating women who run the world. Sembène centralizes the conflict between the women (Diouana and Madame) of the film to demonstrate the ruinous effects of social hierarchy and chains of power in lived, individual experiences. Inevitably, Sembène tells us, stratified, status-oriented relationships and social contracts produce disparagement and marginalization. Although this film provides a direct commentary on identity displacement in the postcolonial experience, its message can also be applied to broader contexts relevant to race and gender.

Like sexism, racism is a problem that is structural and endemic to American culture and needs to be addressed systematically, along with class and all other systems of domination.

Celebrating women’s power requires us to critically examine the complete history of women’s struggles for liberation in the feminist movement and beyond. An analytical inspection of the role of race in the history of feminism confirms that a racial, classist struggle for cultural dominance became an early impetus for feminism in the United States. To achieve empowerment for all women, we must have penetrating, self-aware conversations about the effects of social power and cultural domination in an intersectional context. Let’s start a conversation. Can you name any compelling representations in TV and Film of female empowerment that become problematic at the intersection of race and gender?