To say that director/co-writer/producer Laura Plancarte’s new film, Mexican Dream, employs a unique approach to documentary content is no small understatement. The film focuses on a Mexican divorcee, María Magdalena, nicknamed Malena or “Male” (pronounced MAH-lay), who fled her abusive husband to Mexico City, leaving her three children behind in his custody. There, with her new boyfriend, she hopes to start a new family and business, then regain custody of her children, and live together under a single roof.

Male’s is indeed a “Mexican Dream.” But the challenges are many. There are few work opportunities for an untrained domestic worker. She had had her tubes tied to prevent further pregnancies with her abusive husband, so an expensive in vitro fertilization treatment can make a new child a possibility. Her new boyfriend has his reservations, as do her children, who still feel the pang of abandonment.

Male’s is an extraordinary story of resilience and optimism. So too is Plancarte’s and her approach to its telling. In the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, she and Male took it upon themselves to forge a new approach to documentary storytelling, allowing the subject to co-write and enact her own narrative, in a unique and expressly cinematic undertaking.

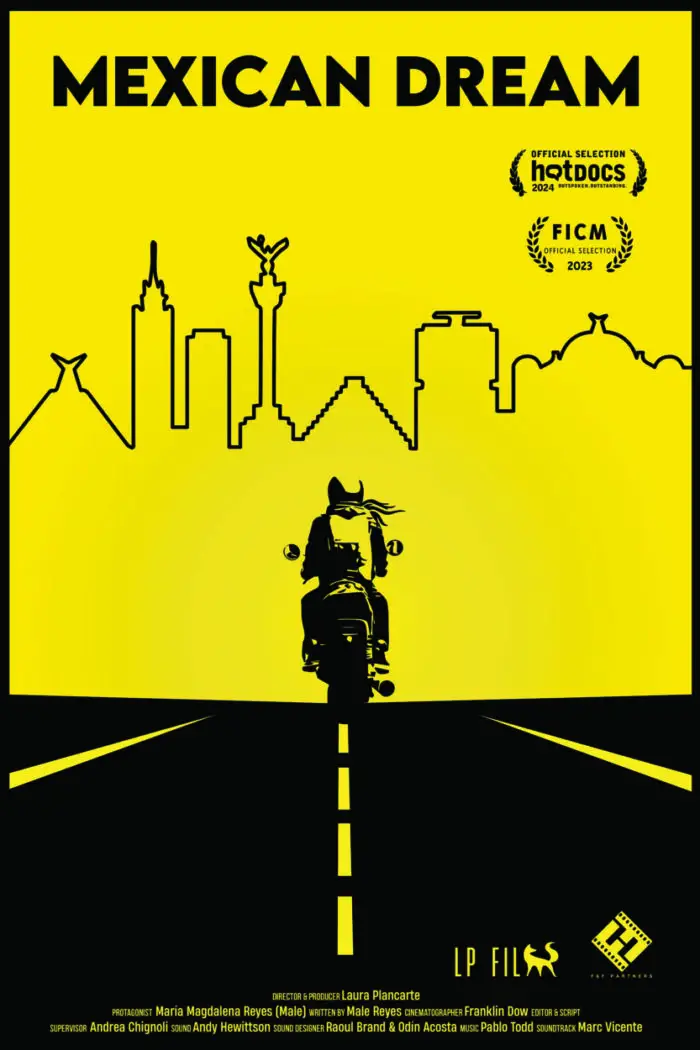

Plancarte, a Mexican filmmaker who lives and works in London, is director of the prior films Hermanos (2018) and Non Western (2020). Following the premiere of Mexican Dream at Hot Docs 2024, she spoke with Film Obsessive’s J Paul Johnson about the making of and reception to her and Magdalena’s film. The transcript following the video has been edited for space and clarity.

Film Obsessive: I’m here today with Laura Plancarte who is producer, director, and co-writer of the new film Mexican Dream and who is taking the time to speak to us from London. Welcome, Laura.

Laura Plancarte: Thank you so much, Paul for inviting me. I’m super happy to be here in your program and with your audience. So thank you.

And I am super excited to discuss Mexican Dream. But before I begin with some thoughts and some questions. Can I just have you tell our audience in your own words what this film is.

Well, thank you, Paul. So Mexican Dream is a film done in collaboration with the main character. Her name is Maria Magdalena but in Spanish, for short, we call her Male (MAH-Lay). That comes from Malena because sometimes Magdalenas are called Malena. And when I started, I wanted to make a film that showed a different perspective on Latin American women. Because in my experience, I have seen many films where Latin American women are portrayed as fighters, but also as miserable, like struggling, but just like crying and a lot of times in a submissive kind of very passive role. And I think obviously, there are some women that are like that, but many women that we are Latin Americans were not that. And I wanted to find this woman this woman that could be the character of the film.

And so, actually, through a friend of mine, I sent out a call to women in Mexico that were willing to have a Zoom interview with me and explore the idea of making a film a documentary about their life. And I started interviewing many women and the day I met Male. I knew immediately that she was the woman I was looking for. Not only because she’s incredibly charismatic, but it comes across in a very natural way, her force. And also, I was very intrigued by her story. And I thought not only this is the opportunity to show a different kind of portrayal of femininity in Latin America, but also it’s an opportunity to see also a woman that comes from an impoverished background, but through a different lens because unfortunately, what sometimes we do is that we portray people as the job they do, but not as the person they are.

And when I interviewed Male for that first time, it really attracted my attention that she told me So, you know, I was in an abusive relationship, so I’m a victim survivor actually of domestic abuse, but I left that relationship, and I needed to flee my hometown and go on work in Mexico City as a domestic worker, so I could send money for my children because her ex husband was awful. Let’s put it just that way. And but now I’m I’m being able, you know, to, you know, build my own house. And in the process, I fell in love again.

And she was very enthusiastic about it, which I found incredible because she wasn’t lost just in the trauma of the past. And she told me and now I want to have another child. I want to reconnect with my children because the ex husband took the custody of her children away when she needed to go to Mexico City, actually, to be able to send money for them. So she told me I want to reconnect with my children, regain custody, but also she told me I want to have another baby. But for her to have another baby, she would need to do IVF because she had had her tubes tied due to the abuse of the previous relationship. And for me, at that point, it was Wow. So you already have children. Three, they are almost about to become teenagers. You lost their custody. You have a complicated relationship with them. You are finishing your house, you have a new partner, but you want to add to everything now going through IVF and paying a really costly treatment and all of that and all of this together?

It broke completely all the ideas that I had of what could be her dreams. There were shattered on that initial conversation and I thought she’s the person I want to work with.

She’s an incredible subject, and at this moment, this is during COVID, correct, what you have at this point is you have a protagonist and you have a story. But what kind of intentions did you have for making a film at that point?

So basically, we met just before the pandemic. It was January 2020, and the pandemic hadn’t exploded except in China at that point. So we were able at that point to meet and the idea was to start, you know, getting to know each other to be able to do the film. But then when COVID hit, everything was closed. And she and I had started to having the Zoom interviews that we would have Monday, Wednesday, and Fridays, one hour and a half each day. And I told her, that’s the way I work, so we can really get to know each other and I can understand you and you can feel if you want to work with me also if you feel comfortable. But then is when the pandemic closed everything. So the idea that I could be going to Mexico filming with her in her hometown for long periods of time was basically out of the question. So I thought and I said to her, look, these sessions, we need to keep on going because this is how you and I create this bond.

But a film cannot be told by Zoom interviews. So what I’m going to do, Male, is I’m going to send you an iPhone with some accessories like a tripod microphones and everything. And basically, through your iCloud account on the iPhone, I’m going to be able to download the material your film and in your old phone, I’m going to be on Zoom and I’m going to direct remotely. And she was super happy about this because as you have seen, Male is a person that loves adventures, learning new things. So for her, it was an incredible situation of learning, now becoming a filmmaker, and everything.

And for me, it was an incredible, you know, experience to also collaborate since the beginning with the character. It’s something that I hadn’t done before. So since the beginning, it’s not just me observing her, but it was me giving her the tool, so she could actually also film herself and make decisions, and I would be directing on Zoom, but also sometimes she would go on her own and take decisions to film things without having me on Zoom. And as the lockdowns eased, I would travel to her hometown, and then I would film her and her relatives and and and we worked like that for two years.

So there must have been a moment in there where you made the decision that either that wouldn’t work or that wasn’t exactly the film you wanted to make. And as viewers of Mexican Dream will find out, the film that they watch is something similar yet very different. Was it difficult to make that decision, and could you have made the film that you envisioned?

So what happened after two years of working that way is two things, I think happen at the same time and is one, I said, Okay, we’ve been working for two years. I want to see how this blends. So without an editor or anything, I did like a kind of very rough cut of material of footage shot by Male with the iPhone and material shot by me without a crew. And I put it together and I found it really interesting. But I found, as you have seen Mexican Dream, I like cinema, and I like to make cinematic films. And by blending the material, it was it was it felt choppy. And it felt also that it didn’t flow as well, and me knowing Male, I thought that the material didn’t do justice to her, that she was far more interesting and far more powerful than what we had been able to capture working, part me part her, in this way.

So I traveled to Mexico to her hometown because at that point, she regained custody of two of her children, Jhovani and Fatima. I remember meeting her children and I got into Jhovani’s room because he agreed to be interviewed by me. And I remember setting up the camera and everything, and he was very quiet. And then I said, can I record? And he said, yes, I pressed recording, and I hadn’t even asked a question, the boy he wasn’t 15 years old yet, and tears started rolling down his cheek. And he was just crying and crying and crying, and I just looked at him. And I got scared and I thought her children are hurt. And they have gone through many things because since they were born, they were obviously witnesses of the domestic violence in their home. And even though Male needed to leave them in order to be able to find money to be able to support them financially, they felt abandoned and they had a lot going on.

And I felt at that point that they were really young to be accepting to be interviewed. They were accepting to be in the film because their mom wanted to be on the film. But I wasn’t sure they wanted to be in the film. And I got worried because we all have heard stories, you know, really young people commit suicide, doing those things. And I thought, imagine that this situation because of making a film, something tragic happens. And I don’t think maybe this is going to add anything good to them right now. So I said to Male, I couldn’t really talk to him because he’s just crying, you know, and it’s really sad. It’s really difficult. And she told me, yes, I’m very worried too, what are we going to do?

I didn’t know what to do. My relationship with them is just starting, and then is when the idea came to me and I said, why don’t we do something different? How about you and write a treatment of what we have discovered in the past two years. So you and I together, we’re going to do like a summary. And we’re going to think about how we’re going to tell your story. And we’re going to stage it. And we’re going to tell your children if they want to participate because it’s very different to reenact something but not being caught by the camera. But to be able to place yourself in front of the camera and say, okay, I am going to do a scene that I have lived many times with my mom, that is when her children rejected her many times. So I’m going to play it for the camera. And that’s very different than having me capturing moments in the real reconnection of them, that they feel obviously exposed, that it’s just that they forget that I am there with a camera and then suddenly I have the material and the footage where suddenly you know they had a terrible moment. So the children really liked the idea. Male really liked the idea. Male and I started working on that and we basically wrote together for eight months.

This is an incredibly brave decision. And it connotes a great deal of trust that you have in Male, your subject who would become your collaborator and co-writer here. It also strikes me as unprecedented, really, was there anything in your background, your experience, your education, maybe that made you think this is a way to make this film, or did it just seem like the right thing to do at that moment?

I felt the right thing to do. I think it would solve kind of everything in a way because he would take out this ethical dilemma of I don’t want to expose them. I don’t want, you know, but at the same time, how can we do something authentic? You know? How can we build them? Then I had, you know, watched, you know, like Chloe Zhao’s film, who did Nomadland with Francis McDormand, but before she had done The Rider and she had done other films. And even though those films are presented as fiction, her collaboration, for example, with The Rider, right now, I forgot the name of the boy that is the main protagonist [Brady Jandreau]. In reality, he did have that injury that happens in her film. In reality, he does do the rodeo. So In a way, he’s kind of doing a reenactment. His sister in the film is his sister.

What we have seen now in film is that the boundaries between documentary fiction are becoming blurry. So I have seen her work and I really like her work, and there’s also Italian Neo-realism that works in similar ways. And I thought to myself, why not try something different? And for me, as a documentary filmmaker, at the moment, it seemed the right decision because it had happened to me before that you work and then you feel that maybe you exposed your character, even if in the edit, you try to take away all sensationalism and you try to just put the things that are necessary to be able to tell the story and to do a fair portrait. But that’s always where I have felt uncomfortable.

I remember I was working with a producer and he was telling me, You need to separate yourself and not be so involved with your characters. And I told him, that’s easy for you to say because you don’t know them. And you haven’t had that relationship with them. But for me, I felt that bringing a pure observational documentary to Male and her children would only bring harm future for them because I think they needed to live their own lives on their own terms.

And it allowed you to make a film that was expressly cinematic. As I started watching it, I had not read the press notes. And it was thinking to myself that this is the most cinematic documentary I’ve ever seen until a point just a few minutes in when I realized it was so cinematic, it literally could not be a traditionally observational documentary. But part of the risk there is that your subject has to be able to perform also as an actor conveying herself. And that cannot be easy to do! Credit to Male for really doing just a wonderful job there in front of the camera in the resultant film.

I think Male is extraordinary. And I think she deserves all of the recognition from everybody because the collaboration was something very interesting, In the film there’s a moment, for example, that she’s standing in front of the mirror and she cries and has a very emotional moment. And it’s not that I directed her and told her, Look Male, you go in front of the mirror, and now you’re going to cry. Because that’s not our collaboration, it is not that when I talk about writing together, is not that we wrote a scene—Here is where Male cries. It was here, we’re going to do the moments that you lived at work in your little room by yourself when you didn’t have custody of your children. And the way she interprets that comes from her.

And for me, what makes it really empowering is the lesson is that it’s very different than I would have caught Male with my camera. In the moment where she was crying, but she didn’t want to be seen. And it’s very different that Male at that point, when I told her, okay, so we are here in your room. Here is the moment where you express what was said to be without your children. And she decides to put herself in front of a mirror with a picture of her children. And she just told me, give me some time, and I just moved back and she just cried on her own.

But in that moment, she’s taking the decision deliberately: I want other women, other families, other men to see me crying and what it felt to have had my children taken away from me and that I needed to work in a foreign, in a faraway place, away from my family, away from everything. And for me that makes the difference is that she is the one taking the decisions and saying, I’m going to communicate this. And for me, Paul, this has been a revelation. Because I wasn’t expecting it and it actually shook everything because it really, you know, makes me want to continue working this way because it’s incredible to be able to be in the same boat and it’s incredible to be able to collaborate.

And obviously, to be able to do that, you first need to spend at least two years with the characters as if you are making a pure observational documentary because first, they need to get used to being filmed. They need to get used to the camera. They need to build this bond with me. Slowly then afterwards, we can make decisions together and we can decide this. But it was incredible that—and this might sound strange to you—if you look at certain segments of the material that Male and I shot previously, you know, when she was on the phone and I was going on my own to film her, if you see parts of that, and you see the actual film, there’s more naturality in the staged film when she reenacts herself than in the material when we were working the other way.

And for me, I thought that what happens is that when people feel at ease and on their own terms, they’re going to be able to tell you and express how their lives have been. Their barriers also go down because they are the ones that are making the decision and they are not worried, they’re losing control of having you there filming them and then that you are going to capture the moment where they fight or they look bad or whatever it is. And it’s really as you see the film, there’s not, I don’t think, one moment in the film where you see her acting or you see her relatives acting.

I don’t feel that Male [ever seems like she] is performing. It feels very genuine and very authentic. Here she is, carrying it throughout every scene and working through some pretty traumatic material. And I don’t know how much you thought about this, but it also strikes me that your film really rests on that performance. And if its feels contrived or inauthentic, that’s deleterious to your film. But the end result is really remarkable.

How did the process go, then, for casting the other roles in the film?

So basically, nobody is acting somebody that they are not. So her parents are her parents. Edgar, the boyfriend is who used to be her boyfriend. For the breakup we had to do so basically we had to film the actual film was done in two weeks because exactly, they are not actors. So nobody can take, you know, take so much time out of work. So we needed to film it in two weeks. And then we had to do a pickup shoot later in the year because she had broken up with Edgar. So we needed to do that part. But it was everybody’s like, you know, her friend, Carla is her cousin, the other girl that works with her and that is her friends, you know, the one that they go out dancing, Juanito, he is a chauffeur. And the doctor is the doctor that does the the other women that are doing the IVF treatment are all is a group of women that Male got to know. And that’s how she changed her mind about the IVF. So everybody, there’s no actors.

Laura, where and when will people be able to see Mexican Dream? I know it’s on the festival circuit right now.

Yes, exactly. It’s in the Festival circuit at the moment, and we had a really great news that it won in Doc Barcelona and we got distribution in Spain, which for me has been incredible. We’re going to have theatrical release in Spain. The distributor promised at least 60 cinemas broadcasting VOD. And I’m hoping that we can get a deal like that in the US and Canada and in Mexico and other parts of the world, because when I presented the film in Hot Docs it was for the first time I saw it with a non-Spanish-speaking audience. And I realized I confirmed that this is a film that is universal. That is not just for a Latin audience. It’s a film that is universal because it’s about being a woman, it’s about family, it’s about parenting, it’s about love relationships. And I think it can touch anyone. So I hope that soon I can tell your audience and invite them to watch it somewhere in the United States.

I hope they get the chance to do that soon too, as well, Laura. It is a film that really speaks to second chances in life. And I love your subject Male’s optimism and perseverance and resilience. And I also admire yours in making this film under some complex circumstances and with a unique kind of hybrid approach that I think works incredibly well for this film and which I’m in particular drawn to. So thanks so much for your time today.

Thank you so much, Paul. And thank you so much to all the audience of Film Obsessive. I’ve been very happy talking to you. Thank you.