This weekend, the Netflix special Bo Burnham: Inside will enjoy a surprise theatrical run in more than 400 theaters in the U.S. and Canada. After his musical comedy scored six Primetime Emmy nominations for Outstanding Variety Special (Pre-recorded), writing, directing and music, Bo Burnham is poised for an even broader audience. The theatrical release follows Netlfix’s continued expansion into theatrical exhibition and hints at Oscar eligibility for the thirty-year-old multihyphenate composer-performer-writer-director-and-now-editor. With its dizzying effects, intimate candor, and contemporary perspective, Inside is both the logical culmination of Burnham’s work to date and a work that feels sui generus, a one-of-a-kind Man with a Movie Camera for the lockdown age.

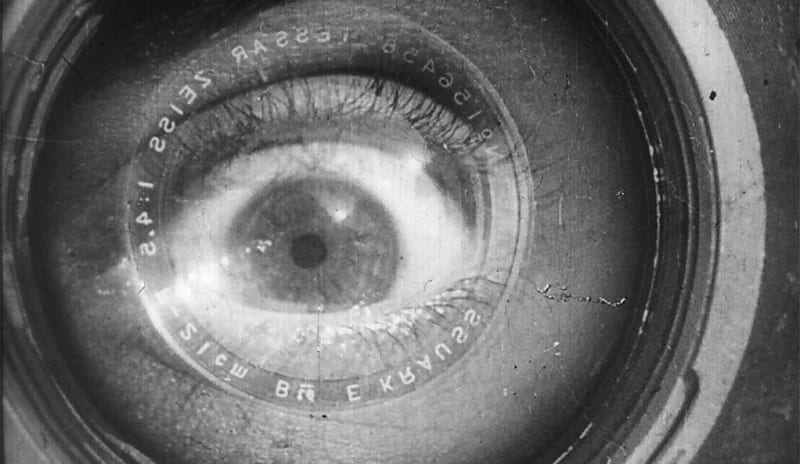

To evoke the 1929 Dziga Vertov classic in a review of a Netflix “comedy special” might sound spurious on the surface. Vertov used every cinematic technique then available to him to document 1920s life in the Ukraine, his own camera and operation of it a significant part of the film’s loose narrative arc. Vertov’s camera could, and did, go nearly anywhere and would often appear as its own character. Split screens, canted angles, extreme close-ups and long shots, tracking shots, reversed footage, stop-motion, all edited in a frenzy of fast motion, slow motion, freeze frames, match cuts, and jump cuts, Man with a Movie Camera charted the activities of Soviet culture with careful attention to presenting them in a robust, rapidly edited, and wholly avant-garde work of experimental filmmaking.

There is in Vertov no single central protagonist, indeed no named individual characters, only the collective citizenry of the Ukrainian communities. Though silent, it has always been performed with a musical score composed to convey its spirit. An impressionistic montage of unbridled hubbub, Man with a Movie Camera aggressively bends time and space, fiction and reality, perspective and image to create a unique cinematic experience. Upon its release it was poorly received for its innovations: Vertov’s contemporary Sergei Eisenstein called it “pointless camera hooliganism” and many were perplexed by its breakneck editing. Today, however, it is revered as one of the best films of all time (critics ranked it #8 of all time in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll), among the most influential and distinctive films ever made.

Curiously, I couldn’t help but think of Man with a Movie Camera as I watched Bo Burnham: Inside. I’ll confess some contrasts are pretty glaring. Thousands of people must be depicted in Vertov, Ukrainian life throbbing and pulsing with the outdoor physical activities of sport, leisure, work, and citizenship. Burnham’s is truly a “one-man show,” the performer the only visage onscreen for its 87 minutes, its setting limited to a single unadorned room furnished with only the flotsam of his recording equipment and the effects they provide. Vertov’s was a picture that characterized perfectly the exuberance of its age’s idealistic urbanization and industrialization. Burnham’s, in contrast, is for all its humor a sobering reflection on our pandemic age, in particular the dependence on social media, the impact of isolation on mental health, and the meaninglessness of modern life. But like Vertov’s, Burnham’s film is a spectacle of cinematic technique radically inventive for the limitations that frame it, and it may come to be every bit as much as an exemplar of its time as was Vertov’s of his.

Loosely arranged as a set of musical performances that constitute a broad narrative arc, Inside takes place inside a single room in Burnham’s house, largely unfurnished, marked by a single window and a door frame several inches too small for the 6’5” performer. Its only furnishings are simple: a stool, a desk, musical instruments and the tangle of lights, cables, filters, cameras, microphones, displays, sliders, tracks, computers, etc. that he uses to record himself. The set is simultaneously restrictive and liberating. While I assume Burnham is free to roam the rest of his house (or even community), limiting the setting this way necessitates and motivates Burnham’s inventiveness. The presentation, in fact, seems like Vertov’s, almost kinetic, and at times dazzling in its array of effects.

Those effects are typically practical and often primitive. In the opening number “Content”, Burnham is first lit by a single small LED panel. But when he dons a headlamp and aims it at a mirrored ball, the scene transforms into to a glistening starscape. In “White Woman’s Instagram” Burnham concocts an elaborate montage of Instagram clichés with a canny array of props, filters, and poses. “Face Time with My Mom (Tonight)” mimics the vertical aspect ratio of the smartphone app with split-screens and overlays. The lyrically dexterous “How the World Works” is comically lo-fi as Burnham dons a cheap white athletic sock for his duet partner. But not only is the presentation charming, it’s also a pitch-perfect metonymy for the contemporary practice of social-media sockpuppetry, where users create secondary fictitious accounts to cheer on their primary ones.

Other songs employ more elaborate effects to take on such topics as labor conflicts and physical intimacy while lampooning new social media genres like the reaction video and gameplay commentary. But Inside is far more than a mere collection of clever camera trickery and charming performances. Burnham has been, like Naomi Osaka and several other celebrities of late, especially forthright about his challenges with mental wellness, in particular his having experienced panic attacks onstage but also his conflicted relationship with his social and digital media fame. In “Goodbye” he raises the question: “Am I going crazy? Would I еven know? / Am I right back where I startеd fourteen years ago?” Inside a single room, inside his own head, is it possible to self-assess one’s own mental health? On the surface here, Burnham is again that 16-year-old uploading videos to the internet to form an identity. In 2021 as a (reluctant) thirty-year-old, he is in a way back where he started, creating and uploading.

Except that today Burnham is nearly as famous as they come. He’s a published poet, an acclaimed writer-director, a successful stand-up comedian, an in-demand actor, and with Inside, a cinematic innovator. That Burnham could fashion such a film, largely by himself, in such circumstances, and for the most part alone is nothing short of remarkable. (Burnham is credited as the writer, director, cinematographer, and editor; the only other credits are for post-production color correction and online editing.) Bo Burnham: Inside is not only visually spectacular, intellectually engaging, and often hella funny. It’s also a wildly innovative work that, just like Vertov’s in his day, suggests new and radical possibilities for filmmaking in its era.

When film began in the 1890s, for a time it might have become anything. But following Porter, Méliès, Griffith, Weber, Micheaux and others, it focused primarily on fictional dramatic narrative, its length largely a matter of the physical manifestations of the medium, ones that lasted for nearly a century. But film could have been something else, less narrative, less overtly fictional, less dramatic, less scripted. In the future what might we watch? And where will we watch it? Will those Tik Toks that so resemble Méliès’ first camera tricks dominate? Or the long-form seasonal storytelling of subscription streaming services? Or some other as-yet-uninvented phenomenon? Inside makes clear that what we have come to know as film is in a period of radical, maybe even unprecedented flux, some of it wrought by the pandemic that frames Burnham’s performance and insights.

So what exactly is Bo Burnham: Inside? A carefully composed work of fiction or a cleverly-shot performance documentary? A television special or a theatrical release? A blithe satirical comedy or a tragedy for our pandemic age? A heartfelt plea for understanding or a brilliant disguise? Any of those are reasonable and not inaccurate descriptions. Like Vertov’s 1929 classic, Inside is something new, but expressly of its time, intensely and exuberantly cinematic and artful. It also adroitly characterizes and lampoons many of the key concerns of our time. Burnham’s Inside is, in essence, a millennial, musical Man with a Movie Camera for a modern lockdown age, one well worth our while whether on the streaming box or at the local cinema.

Bo Burnham: Inside includes implicit and explicit reference to suicide as well as the following end note: If you or someone you know is struggling with their mental heath of thoughts of suicide, information and resources are available at www.wannatalkaboutit.com.