As a filmmaker, Jafar Panahi has been a prolific, vital force in Iranian cinema for more nearly four decades since his 1995 debut, The White Balloon. His increasingly self-reflexive works exploring artistic freedom in the face of oppression have won him legions of fans worldwide—and the ire of the Iranian government, resulting first in a 2010 ban from filmmaking he continued to ignore. Then, in 2021, Panahi was arrested and served a six-year sentence for his outspoken views. As his most recent film, No Bears, debuts in North America this month, Panahi sits behind bars—to the outrage of cinephiles and human-rights advocates nearly everywhere.

The work itself might make for a gently comic filmmaking farce à la Truffaut’s La Nuit Americaine were it not for the harsh realities of its maker’s plight and the eventual complexities of the plot. In No Bears, Panahi plays a fictionalized version of himself (as he has before in Closed Curtain and Taxi), a filmmaker banned from Iran and so relocated to a rural village across the border in Turkey, where he hopes to direct—remotely, with the help of his assistant director Reza (Reza Heydari), his cast, and small crew—a film set and shot in Iran. Doing so is no simple task, as Panahi must communicate his directions and review footage via videochat, even when signals are weak.

The film Panahi is making seems focused on a romanticized flight from Iran, a fictional if fact-based tale based on forged passports and assumed identities, one that makes possible what for so many is not: freedom from oppression. But at the start, its foibles pale in comparison to the ones Panahi finds himself in the midst of in Turkey. There, he has rented a small room from a local man named Ghanbar (Vahid Mobaseri) and found himself under the suspicious eye of the village sheriff (Naser Hashemi).

There in Turkey, Panahi photographs the locals to learn their customs, which he finds quaint and curious. There is a sense that the big-city filmmaker with his omnipresent camera gear, shooting and surveilling all that he sees, might pose a threat to the rural Turks and their long-held traditions. And soon matters escalate: two young lovers are said to have been found in a compromising position, given that she is betrothed to someone else via an arranged marriage to a local hothead, and a photo Panahi presumably took of them is proof. Despite the best efforts of his obsequious landlord Ghanbar to keep the peace, nearly the whole village, it seems, has a stake in Panahi’s photo: the lovers, the families involved, even the sheriff.

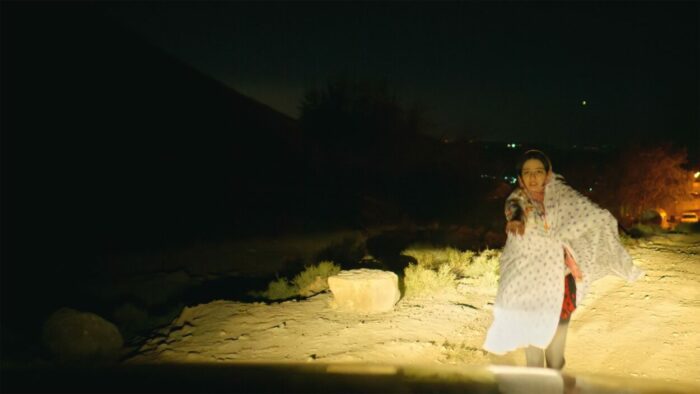

So for a time in No Bears, Panahi’s problems seem mildly comic: trivialities that interrupt his work. But even as the locals are unfailingly polite, their requests are also increasingly demanding of Panahi’s attention. The local scandal pulls into sharp focus the opposing forces of tradition and modernity as tensions between factions threaten to turn violent. Meanwhile, on his film set across the border, more trouble is brewing. And just as in the recent 200 Meters, any border crossing is fraught with tension, especially those that must be conducted in the middle of the night with complicated arrangements made by shadowy networks of human traffickers.

As it turns out, the Turkish locals aren’t the only ones who are unhappy with Panahi. So are his actors, especially the female lead Zara (Mina Kavani), who explodes at her director. His fiction is unsatisfying she says, a betrayal of what was promised. The actors were told it would be the story of their people in his film, but what’s taking place in it is instead nothing but a fantasy, a tale of flight to freedom that ignores the consequences of oppression for all those left behind. Though Panahi betrays little reaction, here or at any moment in the film, despite the increasingly hostile tones of all around him, it’s clear the accusations are fair.

Not only do the accusations sting; they have consequences. Zara disappears. The film shoot is in jeopardy. And meanwhile in back in Turkey, Panahi finds himself cornered by nearly the whole town, now adamant that he produce the photo he took, and subject to a court where his technological acumen and photographic evidence mean nothing to a village where justice is determined by oath, bloodline, and tradition. Making a film from across the border may have been an act of hubris and an affront to the locals, and it’s doubtful his finished product will ever see the light of day.

No Bears takes on even greater meaning given that its maker is as of this writing still imprisoned—for the very act of making films. One can hardly question Panahi’s abilities and determination as the filmmaker of No Bears; yet the filmmaker he plays in No Bears seems acutely oblivious to the ethical dimensions of his practice. He’s distressingly inattentive to the very real stories of the Iranians desperate for freedom and politely dismissive of the local customs and people. It’s a less-than-flattering version of himself Panahi plays, although his doing so allows the film to raise, slowly and methodically, its own set of questions about the ethics of filmmaking.

Can or should, for instance, a filmmaker romanticize flights of escape from oppression? To what obligations is a filmmaker bound to his subjects’ lived experience? On what ways must a filmmaker observing, living with, even filming others bound to provide some degree of reciprocity? Even more importantly, how important is filmmaking itself in the face of a fascism that would imprison anyone daring to speak against it?

Panahi is hardly the only filmmaker to suffer at the hands of Iran’s regime. So had been his fellow Iranians Mohammad Rasoulof and Mostafa Al-Ahmad earlier last year. Just after No Bears premiered at the Venice Film Festival, where it won a special Jury Award, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in the custody of Iran’s morality police, sparking protests against Iran’s theocracy. Iranian actress Taraneh Alidoosti, star of Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning The Salesman and last year’s Subtraction, was also arrested after an Instagram post expressed solidarity with protestors. (She has since been released, three weeks after her arrest, and following worldwide outcry.)

Though its maker remains imprisoned, Panahi’s No Bears speaks volumes. It’s a sly, confident deconstruction of the filmmaking process, a treatise on the tensions between tradition and modernity, and a thoughtful protest against a fascist regime. That a filmmaker of Panahi’s talents can be imprisoned for speaking his mind—for making films—that don’t kowtow to his native government’s theocracy is a crime in itself. That’s one reason to see No Bears. One, I’d say, of dozens.

No Bears (Khers Nist), written, directed by, and starring Jafar Panahi, opens Friday, January 20th at the Gene Siskel Film Center in Chicago. In Persian and Azerbaijani with English Subtitles.