Rare is the film with the emotional power of Maryam Touzani’s quiet, dignified The Blue Caftan (Le bleu du caftan), Morocco’s Official Selection for Best International Feature at the 95th Academy Awards. At first glance, a film about a Moroccan maalem, a master tailor who with his wife takes on a new apprentice, might not seem the most likely of setting for profound drama. Yet there is in The Blue Caftan (the title referring to an elaborate garment the maalem crafts to order for a demanding customer) meaning woven from Touzani’s elaborate stitching together of subtly introduced plot threads, ones which when brought together create a deeply emotional work.

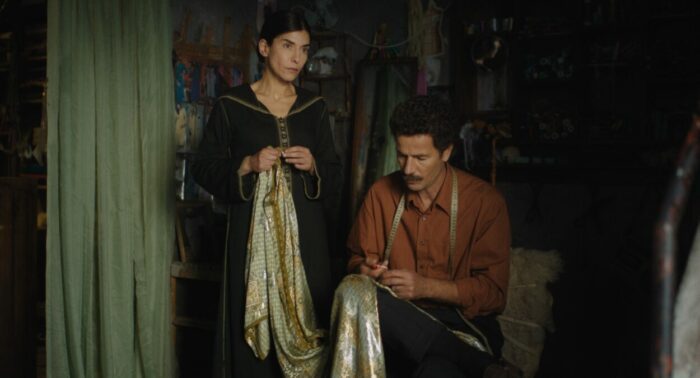

The stakes are higher than the simple creation of a garment in a bartered exchange. The maalem, Halim (Salem Bakri), is a religious, fastidious craftsman; his wife, Mina (Lubna Azabal), devoted to his success. Their old-fashioned garment shop sits in the center of their town’s medina, where customers are still occasional, even though Halim’s artisanry is a fading skill. Touzani focuses her close-up lens on his garment work: his soft, dexterous hands lovingly caressing elegant silks, skillfully guiding his needle through fabric to repair hems and embroider details.

The sensuality of Halim’s craft is not lost on his new young apprentice Youssef (Ayoub Missioui), whose romantic interest in the maalem is made apparent from the start. And Youssef’s beauty is not lost on Halim, who has found himself a clandestine routine of visiting a nearby hammam for brief sexual trysts with other men behind closed doors of private stalls. Halim is neither oblivious to nor dismissive of Youssef’s longing gaze. Meanwhile, Mina observes the interactions of her husband and apprentice with a wary, guarded eye.

Touzani’s exploration of male homosexuality is set in a country where same-sex sexual activity is criminalized with sentences up to three years’ imprisonment. That is itself a daring and transgressive act. Halim’s anonymous trysts could land him in jail, as could pursuing a relationship with the younger Youssef. The Blue Caftan is only occasionally explicit, for the most part implying sexual desire metonymically through the loving texture and caress with which Halim and Youssef practice their craft.

As Youssef pursues Halim, it remains clear that husband and wife are still in love, if lacking passion. Mina, normally cautious and reserved, begins to exhibit some different behaviors: initiating middle-of-the-night sex, enjoying a night out on the town, even acting boisterously in a crowd, all of these we are given to understand are out of character for her. But Touzani will provide a reason that explains Mina’s growing lack of reserve.

A final thread of The Blue Caftan‘s plot takes place in their small shop and gives the film its title. A boorish customer has enlisted Halim to create the eponymous gown, a beautiful work of petroleum blue silk embroidered with delicate gold trim. It’s an elaborate affair, and Touzani relishes in the sensuality of its making: Halim guides Youssef through the slow cutting of fabric and deliberate stitching of accents, the two’s hands delicately touching and intertwining.

Who, then, deserves to wear such a beautiful garment? It’s the kind of question that might have been asked a century-and-a-half ago by a Maupassant or O. Henry. Without revealing any of The Blue Caftan‘s marvelous surprises, suffice it to say that Touzani masterfully weaves together a creation of equal delight: Mina’s behavior, Halim’s affair, Youssef’s desire, the garment itself all figure in a series of several subtle revelations rich in emotional impact and thematic meaning both.

In fact, the last of these—the film’s final revelation, one which a more savvy reviewer might have predicted—reduced me to a bawling mess. It was clear all along that Touzani and co-writer Nabil Ayouch were incrementally imbuing the caftan itself with a highly charged meaning, but to what end exactly escaped me until its reappearance in the film’s penultimate scene, one that stunned me with its brilliance. Perhaps events near to my own life recently had left me especially sensitive to the film’s conclusion; perhaps the brilliance of The Blue Caftan‘s final revelation had simply worked its narrative magic on me. Either way, the film does what great cinema can: create empathy between viewer and character.

I would think it a sufficient accomplishment if Touzani’s film dared solely to explore same-sex relationships in a setting where such activity were subject to three years’ imprisonment. The Blue Caftan does that and so much more: through her careful characterizations, elaborately constructed plot, and a remarkable conclusion, the film presents its own vision of what love truly means and of who can truly enjoy it. Perhaps that vision is naïve—its characters are more forgiving and generous than the law of the land they inhabit—but it’s expressly cinematic and genuinely affecting nonetheless.

All three leads are excellent. As the young apprentice Youssef, Missioui has the least to do of the three, but he projects the enthusiasm of youth, a willingness to learn, and a sensitivity beyond his years. As Halim, Bakri is a man of few words, but his stoic glances are interrupted by the slightest of smiles that convey his love for Mina and Youssef both. Azabal carries the bulk of the film’s emotional weight as she deals with customers, assesses her husband’s affair, and faces her own mortality.

One might be tempted to think that a film in which a husband engages in an extramarital affair with a younger man should be read as an indictment of traditional marriage, but The Blue Caftan is in truth the exact opposite, a film that defends and honors the vows its characters take. In demonstrating the love and commitment a partner can devote to a spouse, Maryam Touzani’s brilliant film teaches us that we have only a lifetime to give to the one we love.

Winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival where it premiered Un Certain Regard, The Blue Caftan (Le bleu du caftan), directed by Maryam Touzani and starring Lubna Azabal, Saleh Bakri and Ayoub Missioui, opens theatrically in New York and Los Angeles February 10, 2023 with other cities to follow. In Arabic with English subtitles. Distributed by Strand Releasing.