In the first part of A History Of Kung Fu, I took a look at the birth of the genre. From a history steeped in Chinese opera to its eventual transition to film, it became a cultural phenomenon, but one that seemed destined to forever languish in the country of its origin. This was because nobody was looking to import Asian films. Meaning that the lucrative American and European markets were closed, but they wouldn’t stay closed forever. It would take the business acumen of four brothers named Shaw to break down these doors and though it would require an almost infinite amount of patience, when they finally managed to export their movies to the world it turned out the world hungered for Kung Fu far more than anyone could’ve ever known.

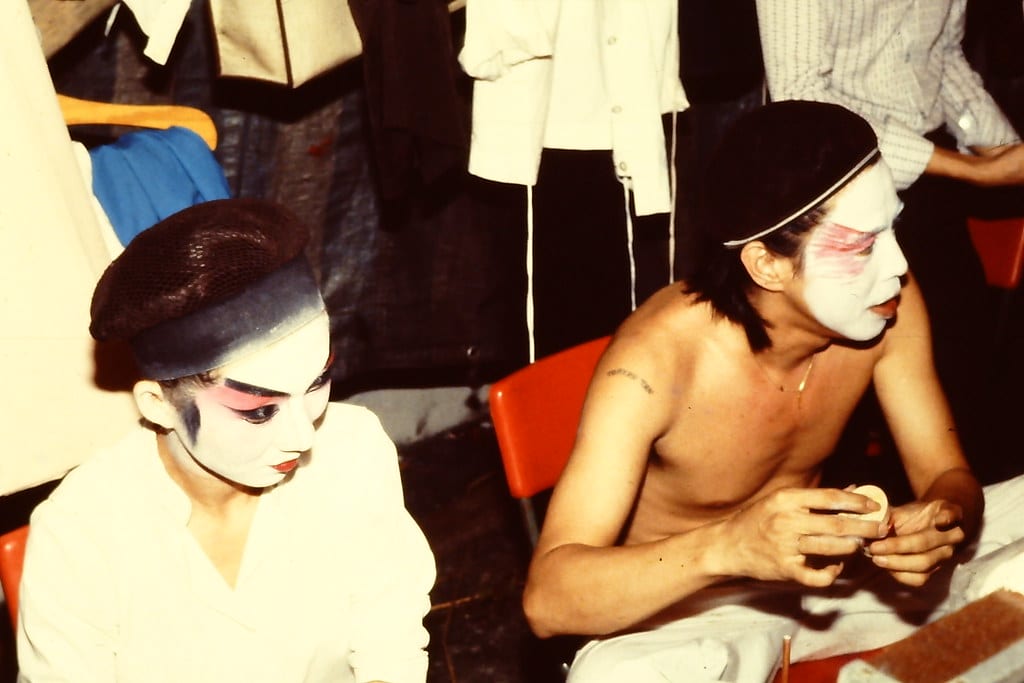

As with most things Kung Fu, the beginnings of the Shaw Brothers Studios would be steeped in Chinese opera. It all started with the eldest brother, Runje Shaw (B. 1896), who was the definition of an entrepreneur. He’d graduated from Shenzhou University, at the tender age of 18, with a law degree and had gone to work for the local Shanghai court before branching out into textiles, silk, and anything else he could sell. He also founded the Huayou Egg Factory, but this wasn’t enough for the eldest Shaw. In 1922 he took on another role, the day-to-day running of the Xiao Wutai theatre. This would become a pivotal moment in the career of the Shaw Brothers as during this time three of the people he worked with, Zhang Shichuan, Zheng Zhengqiu, and Zhou Jianyun would form the Mingxing Film Company. They would release their first movie, An Orphan Rescues Grandfather (1923),and it was such a huge success that it would inspire Runje to start the Tianyi Film Company two years later.

He was joined in this venture by his brothers, Runde Shaw (B. 1898), Runme Shaw (B. 1901), and Run Run Shaw (B. 1907), and thanks to the Runje having his finger on the pulse of what the general public wanted, they were a hit from the get-go. Their first movie, A Change of Heart (1925),would set the blueprint for how the company went about making films for the next few decades. They would focus on the kind of Wuxia films that were popular at the time and by throwing in a mixture of romance and action, they were guaranteed a big box-office whenever they released a new movie.

For the best part of 25 years, they went from strength to strength. They were one of the few companies who refused to make any political statements leading up to WWII, choosing instead to focus on entertainment over any message, and the fans loved them for it. But, sadly, it wouldn’t save them from the fate nearly all filmmakers went through at this time. They would fall victim to the Chinese government banning Martial Arts movies, but they found a way around this by moving to Shanghai and setting up business there. From 1933 to 1937 this worked well, but as Japanese forces were on the verge of invading Shanghai, the Shaw Brothers got out of dodge and headed to Hong Kong, hoping to establish a base of operations, far from the meddling fingers of any country. It didn’t work. When the Japanese successfully invaded, they took control of all the brothers’ assets, including a chain of nearly 140 cinemas which they used to force pro-Japanese propaganda down the Chinese people’s throats.

The war wasn’t kind to the Shaw Brothers. Their studio in Hong Kong was burned to the ground and both Run Run and Runme spent a lot of time on the lamb from the Japanese occupational forces. In fact, Run Run claims that during this time he and his brother buried $4 million in gold and other precious items in their back garden, returning to dig it up after the conflict had ended and using it to help rebuild their empire. Still, they survived, and in post-war Shanghai and Hong Kong, they would thrive. Yet, they’d have to do it without Runje, who had had enough of that lifestyle and retired from the industry to live out the rest of his life, quite happily, in Shanghai. He died there in 1975, aged 79.

With Run Run Shaw now at the reigns, the Tianyi Film Company would rise from its literal ashes to become the all-conquering beast known as the Shaw Brothers Studios. It would start simply enough. After the war, the Chinese government banned any of their films from being sold overseas. This was done as a way to keep prying eyes from getting an insight into the new communist regime and it was also done to punish those who had left the homeland and settled elsewhere after the fighting was over. Seeing a huge gap in the market, the Shaw Brothers were eager to capitalize and started shifting as much of their product abroad as they could. They got away with this by being based in Hong Kong, which was then under British rule, as well as the part of Shanghai that was under International law. This meant that the Chinese government could not touch them and the money started to roll in. They also started knocking out period dramas as and when the market desired them, but their main source of income was in the Wuxia and Kung Fu genres that the company would come to symbolize.

I could give you a blow by blow account of every single Martial Arts film that the Shaw Brothers Studios released here, but as they released over 1,000 of the bloody things, I neither have space in this article or time left on this planet to do so. We could also spend the next 15 years or more arguing about what the first Shaw Brothers Kung Fu movie actually was, as opinions vary here as well, but instead of doing any of that, I’ll just give you a quick rundown of what you really need to watch if you’re new to this company.

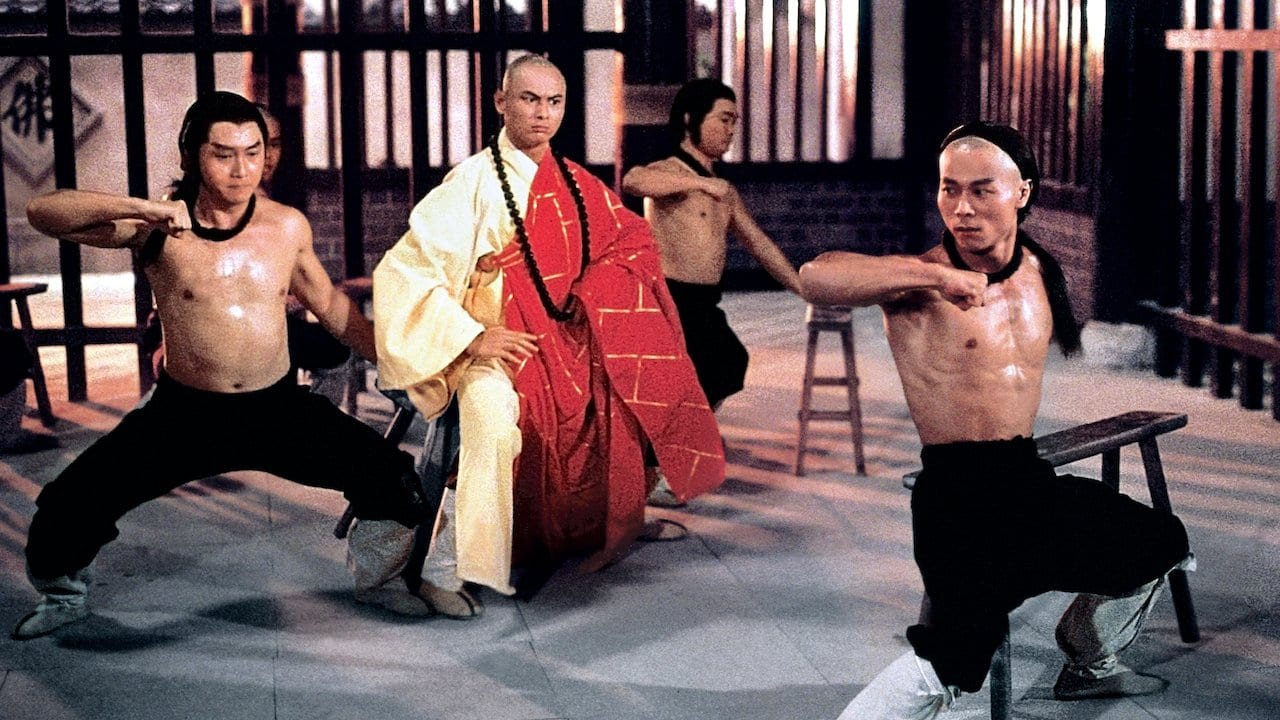

Come Drink With Me, Flying Guillotine, Five Deadly Venoms, The 36th Chamber Of Shaolin, Legendary Weapons Of China—these five are the perfect jumping-off point for anyone reading this that hasn’t yet dipped their toe into the vast library of Shaw Brothers Kung Fu. Each one brings something different to the table, but at the same time, they all feel very familiar, which is down to the influence that Run Run and his brothers had not only on the genre but on the industry itself.

The brothers were shrewd enough to figure out early that the best way of getting the greatest talent working on your pictures was by tying them down to a contract, in the similar vein that Hollywood did during its heyday. This meant directors such as Chang Cheh (One-Armed Swordsman) and Lau Kar-leung (The Eight Diagram Pole Fighter) would not only learn their trade under the watchful eyes of the studio but would also go on to produce some of its best work. But it wasn’t just directors who got this treatment. The list of actors and actresses that worked under the Shaw banner over the years is mindblowing and is just as responsible for their huge success as anything else. Jimmy Wang Yu, Gordon Liu, Cheng Pei-pei, Shih Szu, all these and many, many more cut their teeth within the Shaw Brothers system and it was this combination of acting talent, directorial genius, and brilliant business minds that would push Shaw Brothers Studio into the Kung Fu Hall of Fame.

They say that nothing lasts forever, but the Shaw Brothers Studios gave it a damn good go. They saw off fierce competition from rival companies over the years and even found themselves investing in other films, such as Blade Runner, when the 1980s came around. Yet, by 1985, Run Run Shaw had had enough. Tired of competing with Golden Harvest (who I will be looking at in Part 3 of this series) and fed up with piracy eating into his profits, he closed down Shaw Brothers films and focused instead on the TV branch of his media empire. And though they would raise their head above the parapet during the ’90s and into the early 2000s to make a few films here and there, never again would they reach the dizzying heights they’d achieved when they ruled the Kung Fu world.

As for the brothers themselves, time waits for no man, no matter how successful. Runde Shaw would pass in 1973, two years before his elder brother Runje, at the age of 75. This would be followed in 1985 by Runme Shaw’s death at the age of 85 and, considering how close Run Run was to his brother, may very well have been the catalyst to the surviving Shaw Brother pulling out of the film industry altogether. As for Run Run Shaw himself, well, he would live to the ripe old age of 106, finally shuffling off this mortal coil in 2014, leaving behind a legacy that will never be seen again. The Shaw Brothers are Kung Fu movies and no matter how many people may have imitated their style or tried to follow in their footsteps, their 60-year dominance of the industry will never be bettered.