Suffocated by endless nostalgia, I wasn’t ready for another remake. To my disbelief, Belle has proven to be one of the most imaginative and compassionate animated films I’ve seen in a long time. Mamoru Hosoda reimagines Beauty and the Beast through a contemporary lens with Belle’s mixture of Anime and video games.

An online support network within a game

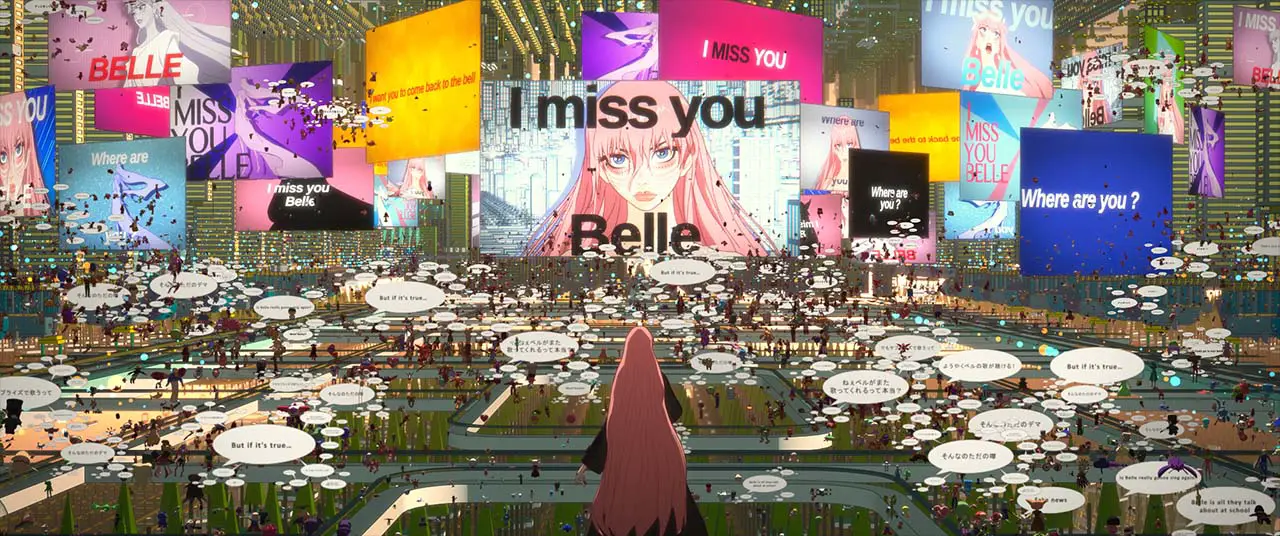

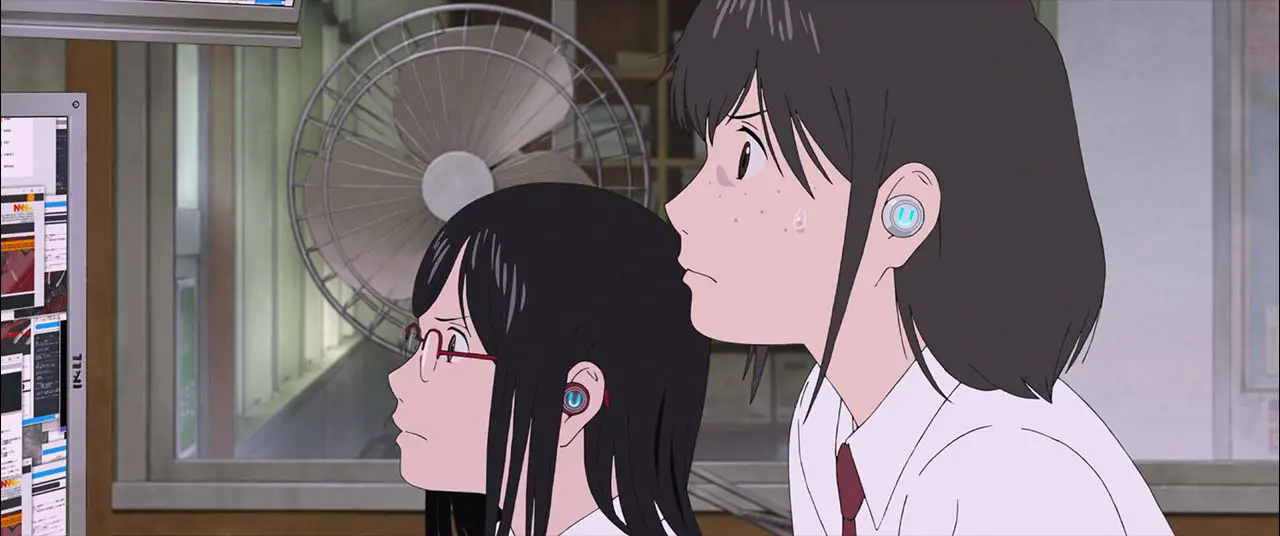

The story splits its parallels between the natural world and the virtual world. In reality, we follow in the footsteps of Suzu, a teenager devastated by childhood trauma. Suzu barely fits in socially because of past scars triggering her crippling anxiety. Thankfully Suzu has a support network of friends to keep her from falling apart. However, their backing pales compared to the world of “U,” a virtual paradise where dreams come true. In “U,” Suzu creates the Avatar Belle, a princess with the voice of an angel. When Belle begins to sing, her voice draws other players in, turning her into an overnight sensation. Vanity inspires Suzu’s newfound affirmation with a community she can’t find at home.

The good times don’t last long when the Beast terrorizes the game. The story’s structure is similar to the material it draws upon; an empathetic princess wants to assist a man cast aside from society. What sets Belle apart from other retreads is its depiction of video games. The existential crisis which haunts the Beast resonates with the identity of someone who could be an online troll themselves. It makes us question what’s going on in that person’s life to cause so much rage. If not for the existence of “U,” nobody could have helped the Beast in the real world.

Filmmakers don’t understand today’s technology even when they try. Most video game-centric movies follow the stigmatization of being catered to adolescents, where Mamoru Hosoda creates a celebratory film about identity. Hosoda embraces video games’ association with oneself. Yes, there are all sorts of abusers online. Still, many seek human connection rather than hate. It’s hard to remember that sometimes.

The heart of the user

Face to face, we’re polite, but behind the screen, we unleash our worst habits since there are almost no repercussions for our actions. Belle isn’t a criticism of the digital age nor an embrace; it’s a balanced examination of current human civilization. Mamoru Hosoda understands the world we live in, one where we’re dependent on computers for escapism when real life can be displeasing. Video games can inspire negative behaviors equal to positive ones. You can choose to be a troll or an ordinary user. The commoner regularly picks the path of the light since they’re us. The gamer isn’t the stigmata of the basement dweller anymore. They’re your parents, your children, aunts, and uncles.

When entering the video game, the film enters a 2D-3D hybrid style. The camera spins smoothly around the virtual world in a motion that’s impossible to render by hand. If every frame is a painting, Hosoda’s Belle is a compilation of equally restrained and bombastic styles. The world outside of “U” is incredibly still, depicting the mundanity of everyday life with the backgrounds resembling elegantly drawn oil paintings and the foreground containing the standard Anime-drawn toon.

Before Belle, I’d been unaware of Mamoru Hosoda’s work. From what I gathered, he’s a renowned Anime director. The category of Anime hadn’t appealed to me throughout my life. My first exposure to it was Dragon Ball Z, followed by Pokémon. Anime through my eyes appeared immature. Whatever sophisticated themes it wanted to explore looked comedic by its character’s laughable extremities. Works like Belle proves not only how wrong I was but how much work I must have been missing out on. Hal, drop me some suggestions!

Video games as a form of art

High art can exist within all media forms exclusive to music, painting, or live-action filmmaking. We need to consider if video games are a form of art we’ve been ignoring. Belle certainly makes a strong argument that it is. Animation’s label of “cartoons” should be re-examined like video games are for children. “U” creates a safe environment children and adults can share. Movies thematically tied to video games fail to conceptualize their meaning. The mechanics are depicted in Tomb Raider or Mortal Kombat, but the spirit is missing. As Belle does, Free Guy captures the community gaming can bring, but it’s depicted on a self-referential corporate level deprived of any real heart. Belle is about the collective tissue games that link us together made by a man I presume gets the culture.

It’s U

The Avatar is a form of expression we’ve been using dating back to having the option of giving Link your name in The Legend of Zelda. Over the years, the idea of the Avatar has been manipulated to reflect a player’s journey. Take the ending of Metal Gear Solid V or Mass Effect 2. Are you good or bad? Season one of The Walking Dead (the game) is all about moral choices and consequences.

We create the Mii in Nintendo in the appearance of what we love about ourselves. In Belle, we deal with a story about revelation through a game’s morality system. Since Suzu is inherently good, beyond the commoner, “U” turns her into a star, rewarding selfless behavior. Saving the Beast from his traumatizer “U” creates a game that saves lives. Games can become a drug for some, like alcohol, but they can be healthy therapy for others. How this relates to Belle is U’s emphasis for compassion over competition, where your heart instead of kill count matters. If not for “U,” the user behind the Beast could be dead.

If you haven’t, I compel you to play Journey, Flower, Shenmue, or The Last of Us to wash those images of Call of Duty and Super Mario out of your head. That Dragon Cancer, a game made by the father of a dying child, incorporated his son’s cancer journey in the game as a grieving process for his family. Belle proves a story can be retold if enough heart and imagination are placed upon the project. Its relationship to loss, online bullying, and virtual compassion are enough to make it worthy of a gander from an outsider to Anime and games. Through trauma, people can connect online or off, where the therapy a game produces isn’t damning to one’s mental health but reaffirming.