I’m certainly not the first to point out that the work of David Lynch draws on the artistic traditions of both German Expressionism and Surrealism. Anyone familiar with these, two of the most powerful art movements of the past 100 years, can recognize immediately how Lynch uses them across his body of work. In his hybridized deployment of these two distinct, but related, feature-filmmaking styles, Lynch has no modern equals (although, as I will argue in a future article, Alfred Hitchcock precedes Lynch’s mastery of these movements). In this article, the first of a series in which I will examine Lynch’s debts to these two movements, I take a look at how we can identify the Expressionist elements of what we might heretofore refer to as Lynch’s “Expressionist Surrealism” (yes, I invented this term, but I feel it effectively describes Lynch’s style).

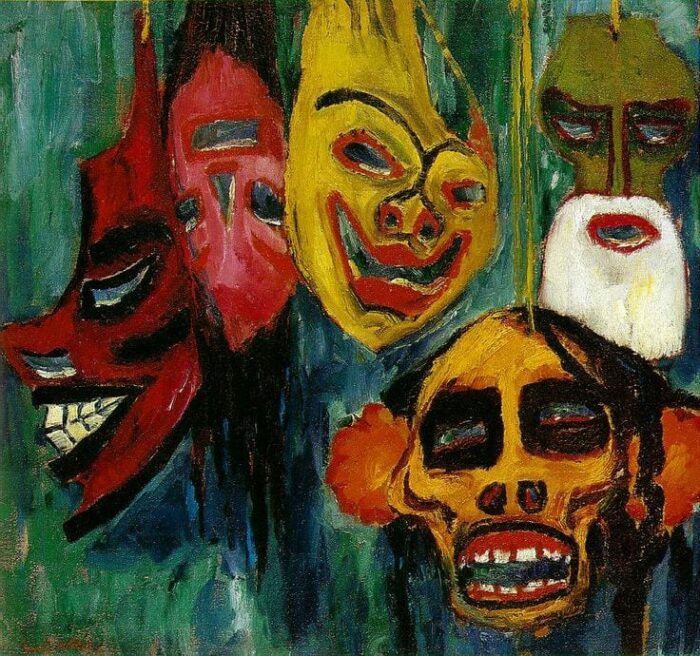

We should start with a definition. What, exactly, is Expressionism (and, more specifically, German Expressionism)? In short, Expressionism is the artistic practice of externalizing dark, internal feelings, emotions, and states of mind, whether in painting, sculpture, photography, film, or any of the other arts. The outlook of this movement is typically grotesque, warped, pessimistic, and, often, quite horrific. German Expressionism began in the second decade of the twentieth century, and it was largely influenced by the dreamy styles of Romanticism so celebrated in a variety of arts in Germany and England over 100 years earlier (think of Fuseli’s famous 1781 painting The Nightmare, for example–see image above). The developing ideas about dream imagery popularized by the likes of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung early in the twentieth century also contributed to the Expressionist style, as did the many sects of Modernist (abstract) art, such as Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, and other Cubist offshoots. The graphic horrors of the Great War (World War I, 1914-18), too, affected all the arts in significant ways, granting to the developing German variant of Expressionism a sense of the grim and grotesque that came to serve as two of that movement’s major stylistic hallmarks. As Emil Nolde’s Mask Still Life III (1911–see below) demonstrates, considerations of the garish and nightmarish characterize not only the subject matter of Expressionism, but its morbid worldview, as well. Choices in colors, compositions, and tone do wonders in such work.

We can see in just one example (of many) how Lynch invokes the Expressionist tradition in an image from Inland Empire (2006–see below), wherein the inner state of mind of the film’s protagonist, Nikki Grace/Susan Blue (Laura Dern) is externalized in a horrific visage that evokes both insanity and insatiable mania (see below).

Expressionism came to German cinema after the Great War, most notably in films such as The Golem (1920) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). The expert cinematography of the era, which sought in such films to establish moody, stark contrasts of light/shadow and black/white, was complemented by exaggerated set design and art design that also spoke to the fractured mental states of the films’ characters. We can recognize the similar

importance of Expressionist set design and art design in Lynch’s work, particularly in Twin Peaks: The Return, in which the many scenes featured in what seem to be inter-dimensional spaces such as The Fireman’s rooms, the Purple Room, or Phillip Jeffries’ room at The Dutchman’s motel (shown below). In each case, these environments play a role in helping us understand more about these characters, their motivations, their desires, and their fears. They also each play a role in the creation of the overall atmosphere of mystery and dread we feel while experiencing Lynch’s world(s).

Of course, Surrealist elements are present in these same images and others, and so, next week in this column, I will continue this discussion of Lynch’s “Expressionist Surrealism” by exploring examples and images of Surrealism in this director’s work. Until, then, drink full and descend.

Woh I love your blog posts, saved to fav!

Simon, thanks! I’ll check out the other possible connections.

I agree that Lynch is expressionistic in his work but I’m not so convinced the dream imargy he deploys is strictly surrealism. The juxepositions he uses are more subtle than straight surrealistic automatism. They are also often employed to make the viewer and listener question meaning which in turn suggests absurdism more than the pysho sexual expressions of the repressed present in surrealism. And by that I mean Camus or Keirkigard as much as Beckett. If you are going to make that link I’d be inclined to look to Miro’s abstract work rather than that of Dali’s surrealism by numbers.

Simon, thanks! I’ll check out the other possible connections.