Fernando León de Aranoa’s ninth film, Loving Pablo, has an uphill challenge within the sweep of its biographical portrait. The film and performers have to meld romance to a monster. In telling the rise and fall of legendary drug cartel figure Pablo Escobar through the eyes of his journalist mistress Virginia Vallejo, showing off sin is easy. The decadent livelihoods built from fortunes of spoils seen in this and other crime films is almost always seductively diverting. Cutting loose to show the heinous violence behind the formidable authority adds flashy shock to remind us not to take sympathy too far out of the amusement.

The morals of romance, however, are different from materialistic or survivalist ones. Those are harder to sell convincingly, side-by-side against riches and power. When done right, a powerful attraction can draw an audience into the rabbit hole with unshakable fascination towards the compelling drama that awaits. Married Oscar winners Penelope Cruz and Javier Bardem may bring mountainous talent and automatic torrid chemistry as a real-life couple, but that heat does not materialize strongly enough within their character portraits of Escobar and Vallejo.

Closely following Vallejo’s 2007 memoir Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar, one that lead to the author’s political asylum three years later, the 2017 movie enters at the end with the narrating Vallejo leaving her beloved country of Colombia in 2006 to cooperate with the United States DEA, led by the keenly observant Agent Shepard (steady, altruistic sleaze provided by Peter Sarsgaard). She is trading testimony for protection and enters confined hotel quarters that trade the white roses and Armani fashions she is used to for uniforms and tactical vests. As she begins to reflect and look back, we are presented with her inside look into one of the most notorious and feared figures of the late 20th century.

Virginia Vallejo first met Pablo Escobar when they were both 32 in the early 1980s. Both had their heads turned towards each other, hers for his humble political aspirations and his for her alluring beauty as a TV personality. She gave him a spry spark away from his wife (Julieth Restrepo) and media coverage for his community outreach. Absorbed into this new elite circle and enjoying the safety among the powerful, Virginia surfs across the social structure orbiting Escobar from the slum-born warriors and the creme of distant affluence, to the rich landowners and narco millionaires (soon to be billionaires) of the decade’s drug boom.

Early on in the film and the central relationship, Cruz’s Vallejo narrates “I don’t care how he makes his money, only how he uses it.” Escobar opens his secrets to her and her vehement request, and gains access to his natural habitat, so to speak. In the beginning, she was willing to ignore the criminal dealings because of Pablo’s philanthropic efforts and the luxury piled in her direction. There was lying and complicity there which Vallejo would not fully realize until the ugliness was unavoidable. This is taking the bad with the bad.

The economic surge and power vacuum of the cocaine industry led to wild social upheaval, clashing political corruption, a landslide of assassinations, retaliatory turf wars, and looming death threats. Escobar grew more dominant, while Vallejo grew more desperate and afraid towards the inevitable and tragic crash. Fernando León de Aranoa (A Perfect Day, Barrio) showers Loving Pablo with rich production value in every frame. Cinematographer Alex Catalán (Marshland) gives the film an intimate yet vintage feel. Paced by Federico Jusid’s ominous score, the outstanding tracking shots slither through the majesty and mayhem found in Alain Bainée’s period-era production design recreations and the incredible set location finds of Mariana Zubillaga and Iva Petkova. The movie merges the toxic with the pristine where both ends of the spectrum bleed into each other for style.

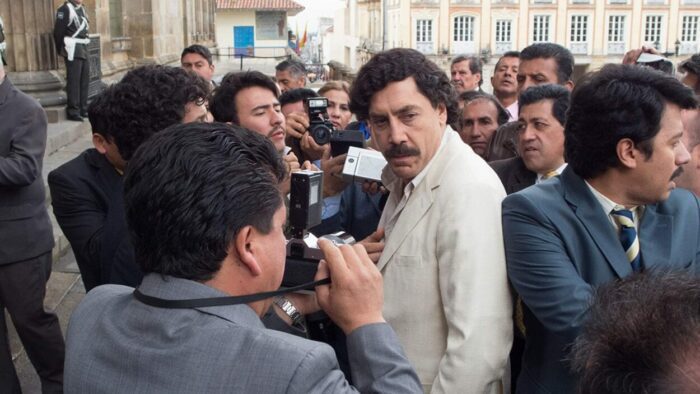

Like the esteemed actors they are, and draped in robust costumes from Loles García Galean and specialist Wanda Morales, Cruz and Bardem radiate every facet of the necessary character transformations. Loving Pablo is the couple’s seventh film together (their eighth would soon follow with Everybody Knows, a chance to work with two-time Academy Award winner Asghar Farhadi). Naturally, if anyone can go toe-to-toe with Bardem’s performance passion it is his own beacon for it. The palpable chemistry between the two Oscar winners was always going to be automatic.

As introduced, the overarching challenge remains making romance out of a villain, enough to soften the depravity of the historical truth. Matching Vallejo’s own findings, Loving Pablo defines that Escobar’s darkness cannot be diluted, making much of this film a difficult and treacherous viewing experience. To its great credit, the merciless edge of Loving Pablo rejects forced cinematic sugar-coating overused in other crime films to romanticize its leviathans. Still, the distance between fascination and rejection is too blurred to find.

Loving Pablo features the dichotomy of a monster. The film is part tell-all and part historical log. Its storytelling magnifying glass is nearly entirely on Javier Bardem’s contrast between the bombastic and the ponderous realms of Pablo Escobar’s personality. So often in the film, his decisions haunt with twisted specification delivered by chilling apathy. The esteemed and revered Spaniard had been circling the most optimal opportunity to place this figure for twenty years. Masking himself in the obesity and deplorable evil intentions, the result is one force of nature playing another.