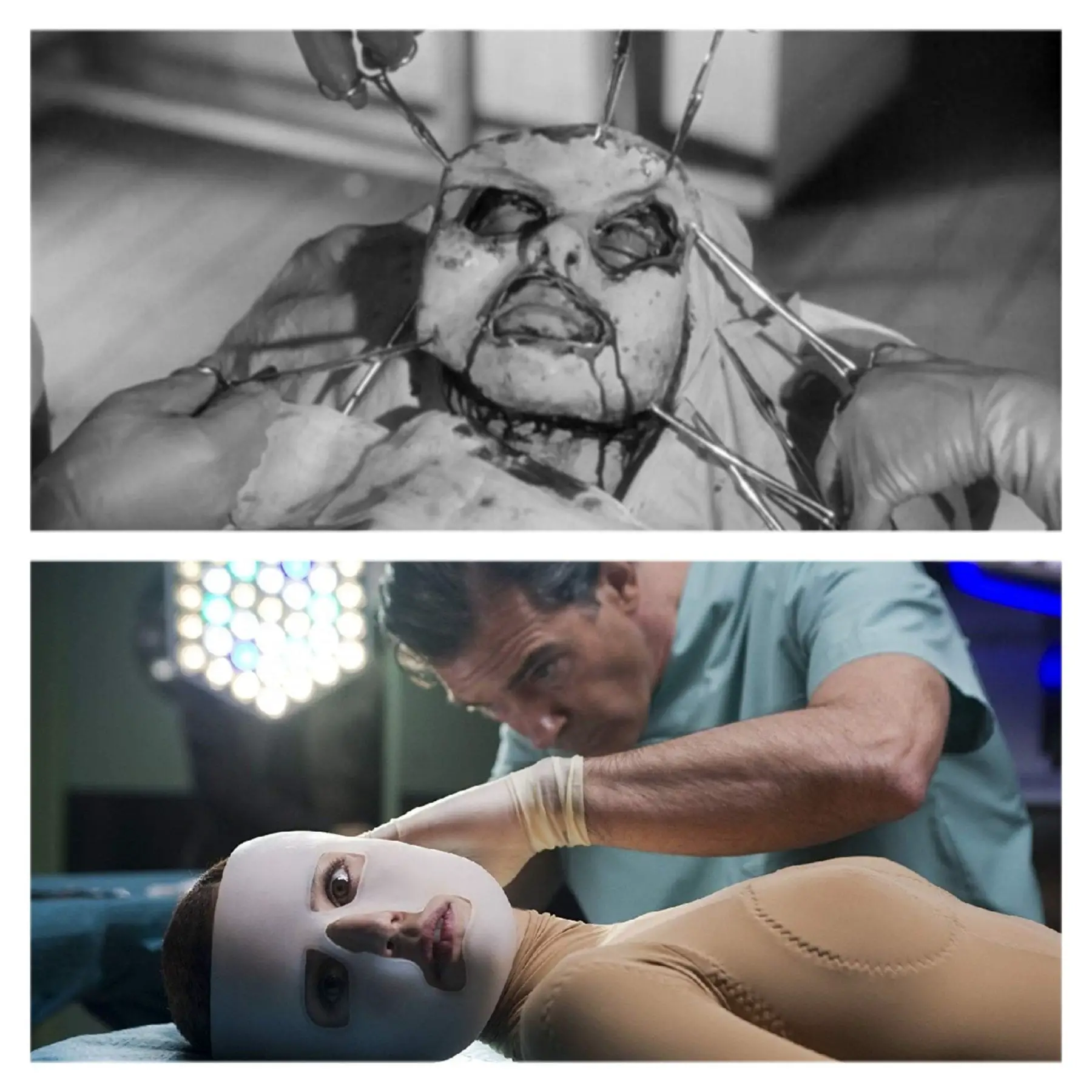

“My face frightens me. My mask frightens me even more”. With these iconic lines, we are introduced to Christiane Génessier (Edith Scob), the bizarre heroine of Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. Released in 1960, the film soon became one of the most controversial of the era, bringing in a storm of negative reviews which, in turn, became so numerous that a reviewer for The Spectator who dared to praise the picture was nearly fired for her remarks. Although it is now viewed as one of the greatest contributions to the cinéma fantastique genre, Eyes Without a Face remains one of the most quietly influential masterworks of the 20th century.

Set in a glossy apartment on the outskirts of Paris, Eyes Without a Face is a tale of regret, vaulting ambition, and vengeance. After his “demonic” driving leaves his once-beautiful daughter’s face terribly disfigured, the acclaimed surgeon Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur) plunges into a guilt-driven quest to restore her face. To do so, he sends his assistant Louise (Alida Valli) to kidnap young women in the most French way possible (by abducting them in her chic Citroën 2CV) and the bodies eventually reach the operating table. With a plot as poetically horrifying as this, it’s no wonder that, in 2011, it caught the eye of one the wackiest and most puzzling directors of our time, Pedro Almodóvar.

The Skin I Live In tells the story of Dr. Robert Ledgard, a brilliant plastic surgeon working in Toledo who, after the death of both his wife and his daughter, decides to experiment with synthetic skin that he can graft onto people. His human guinea-pig for this test is a young woman named Vera (Elena Anaya) who remains captive in his secluded estate, imprisoned in a white surgical mask. The parallels with Eyes Without a Face are more than evident and, at this point, Almodóvar’s storyline may appear weak on originality but he does go on to surprise us with a twist in the narrative. Notwithstanding, far from injecting new blood, this ploy proves the film’s undoing.

It turns out that Vera is not Vera at all, but Vicente, a young man who Dr. Ledgard believes raped his daughter and provoked her subsequent suicide (an act Almodóvar deliberately leaves ambiguous). The surgeon, mad with grief, kidnaps Vicente and performs a vaginoplasty on him, gradually turning him into the alluring Vera. To add to the melodrama, Dr. Ledgard finds himself romantically attracted to Vera and ends up sleeping with her on several occasions. While many of the themes The Skin I Live In are shocking in themselves (Vera is graphically raped, and several people are murdered or tortured), it is Almodóvar’s on-the-nose approach to horror that is ultimately a significant let-down.

When shooting Eyes Without a Face, Raymond Durgnat remarked that Franju ordered him “No sacrilege because of the Spanish market, no nudes because of the Italian market, no blood because of the French market […]. And I was supposed to be making a horror film!”[i]. Whereas the erotic and gory scenes in The Skin I Live In are direct, Franju had to give only a lingering impression of his haunting images to be effective. Robert Ledgard has an overtly sexual relationship with his patient, whereas the implication that Dr. Génessier feels an incestuous desire towards his daughter and anyone who resembles her hangs uncomfortably in the air. At one point, he wryly comments to one of his future experiments that “it would be a shame” if she lost her hair, a sly smile drawn across his face.

Nonetheless, the character that truly stands out after watching both films is Louise, Dr. Génessier’s assistant. Louise is caught between Génessier and his daughter; loyal to the former because he once restored her damaged neck, but sympathetic to the latter’s struggle as a victim. Louise is a foreigner, both literally, as she is not from France and speaks with a heavy accent, and metaphorically, as she does not understand the family dynamics that are unravelling in the house. The viewer can also gain the impression that Louise feels some same-sex attraction towards Christiane, as she tenderly strokes her hair and has a knack for seducing the girls who resemble her. Almodóvar transforms this character into Marilia (Marisa Paredes), a servant who does nothing but complain and is naive enough to let her violent son into the house and abuse Vera. Almodóvar distorts a character so wonderfully complex and full of moral conflicts and reduces her to a hysterical, insane figure worthier of a soap opera than the silver screen.

Franju understood that true horror lies in suggestion. When we are introduced to Christiane Génessier, she hides her face away, keeping it firmly down on a pillow or hidden behind a mask which barely allows her to move her lips, creating an uncanny valley effect where the viewer ends up questioning her humanity. Christiane’s mask becomes a part of her to the point where—in a sequence where Dr. Génessier thinks that he has fully restored her beauty and we see her as she would have looked like before the accident—her face looks almost too perfect and arguably more unnatural than the ivory mask. Furthermore, when Franju does decide to show her scar-ridden visage, the camera is blurred, and the viewer gets only a tantalizing glimpse of what Christiane truly looks like. In the case of Vera in The Skin I Live In, on the other hand, we know what she looks like early on: under her mask lies a stunningly beautiful young woman.

What is frightening about Vera is who she used to be before, and how being transformed into a woman becomes a punishment. This is not a feminist statement, but a debatably transphobic narrative, through which gender reassignment becomes revenge-fuelled torture, rather than a personal choice.

Horror is an inherently subjective feeling, and what qualifies as a horror movie has become increasingly obscure. Franju himself was hesitant to call Eyes Without a Face a horror film as he believed it was “an anguish film […] a quieter mood than horror, something more subjacent, more internal, more penetrating”[ii]. Eyes Without a Face triumphs because its horror is born from atmosphere and insinuation. This is not the case of The Skin I Live In as, instead of pushing the boundaries of the genre, Almodóvar brashly oversteps them and the spine-chilling impact of Franju’s film is lost in overstatement.

[i] Durgnat, Raymond. Franju. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

[ii] Durgnat, Raymond. Franju. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.