Thelma, a 2017 Norwegian mystery thriller directed by Joachim Trier, tells the story of a young woman who goes through a strange transitional phase that would lead to acceptance of her suppressed powers. Thelma is played by Eili Harboe who wonderfully portrays the protagonist’s vulnerability and struggle on the way to becoming her authentic self.

The opening sequence with a snowy landscape sets the tone of the film and hints that we are going to see something quite disturbing. Father and six-year-old daughter walk on a frozen lake. A few moments later we realize that the father considers killing the daughter. At this point, we do not know the reason. Fortunately, he changes his mind and does not shoot.

This sequence elicited several associations in me. It reminded me of many horror films about demonic children. And then, I caught myself thinking about the myth of Oedipus. With all the differences between Thelma’s story and Oedipus’s myth, they have something in common. The theme of killing a child by their own parent is one such thing. Another, and more important, is that both Oedipus and Thelma, by merely existing, are going to threaten the lives of their parents, or we can also say—the established order of the father. Both of them survive and do indeed what they were feared for.

Thelma’s parents decide to raise her with strict religious beliefs hoping that it can prevent the harm Thelma can bring. But what exactly Thelma can do that her parents are so afraid of? We find out later in the film that she has the ability to make anything happen if she truly desires it, even when the desire is not fully conscious. A child may wish that their younger sibling, who has taken their parents’ attention from them, disappear. It is very common. But it would end in a disaster if that child could actually make it happen. This is, apparently, what Thelma did to her baby brother while she was asleep. The baby then was found dead in the lake under the ice.

Ice serves as a metaphor in the film. I see it as a barrier between the conscious and unconscious, or acceptable and repressed parts of Thelma’s mind. This metaphoric ice starts melting after Thelma moves to Oslo to study at the university. Her strict religious upbringing worked fine until the control of her parents loosened. Big city and student life may have many temptations and it can be especially confusing for a girl raised in a small religious community.

Thelma studies biology and looks like she is questioning everything she was taught about life. But real changes start when she meets Anja (Kaya Wilkins), another student at the university. Thelma falls in love with her. This meeting triggers Thelma’s suppressed feelings and it results in an epileptic seizure. It’s a reaction of her body to the feelings that are incompatible with her beliefs.

In parallel to this, Thelma gradually becomes aware of her supernatural abilities. Up until this first episode, she has no idea about those powers. She must’ve forgotten the events of her childhood. As her father says later, those episodes “stopped when she found God as a child”. So, God appears to be the means for suppression of Thelma’s power, and it’s safe to say, of her entire nature.

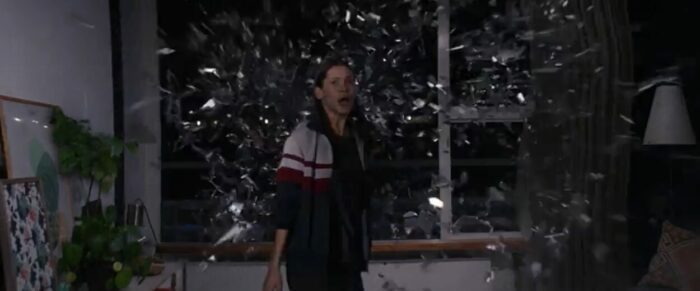

The stress caused by the tension between her feelings and her beliefs results in intensified seizures. Wishing to stop the suffering, during one of her seizures, she makes Anja—the object of her love—disappear.

Thelma’s seizures turn out to be psychogenic, which means that they have no physical substrate. The link to demonic possession stories is obvious. Throughout the centuries all the inexplicable phenomena were attributed to gods or demons. Now we know that people with repressed desires—and not only sexual—may develop symptoms that look abnormal and strange. It’s not surprising that women would have more repressed desires. These desires could develop into symptoms, including psychogenic seizures, that people would interpret as possession by the devil. Thelma is one of these women. Her own parents appear to believe that either she is possessed by the devil or she is a witch, or both.

The idea that evil forces are awakening in Thelma is hinted at through the dream she has the night after her first seizure. In this dream, a snake (not surprisingly, the biblical symbol of temptation, but at the same time of knowledge) enters an unknown building and crawls over a sleeping elderly woman. We later find out that this is Thelma’s grandmother who has been in the hospital for many years, usually sedated with strong medications. The reason is that she had powers similar to Thelma’s.

Knowing family history, the fear of Thelma’s parents becomes even more understandable. And as Christians, they do what they believe is right—they try to suppress the evil that lives inside their daughter. Thelma remembers how her father threatened her with the eternal fire of hell when she was a child. Though, this doesn’t prevent Thelma from having a very close and trusting relationship with her father.

Nevertheless, Trier is merciless towards the father. Perhaps, because, even if somewhat unwittingly, he still is the agent of the oppressive power of patriarchy. After they saw that they could not contain Thelma’s powers anymore, her parents are considering ending this by killing her. But instead, Thelma kills her father—again, in her dream. Ironically, he dies from spontaneous combustion, which reminds eternal fire of hell with which he used to threaten Thelma. Incidentally, burning also was the most popular way of executing a witch.

The opposite is the fate of Thelma’s mother. Even though she is more detached and even hostile towards her daughter, it is her that Trier spares and even cures in the end. Maybe because she too was a victim of that patriarchal belief system. Interestingly, none of the women in Thelma’s family is without some kind of restriction. In her mother’s case, it’s a physical disability. She is in a wheelchair as a result of a suicide attempt after losing her son.

After the death and disappearance of her father, Thelma is free from the oppression that he personified. Thelma can now accept her power and learn to control it. She starts using it in a positive way. She brings Anja back and cures her mother. Thus, unlike her mother, as well as her grandmother who, driven with guilt, turned her ‘evil’ power against herself, Thelma chooses to destroy the oppressive order and live her authentic life.

Still, there is some uncertainty in the end. Thelma is back in Oslo and seems happy together with Anja. From a suffering ‘possessed’ person, Thelma has converted to a ‘witch’ in control of her power. It looks as if she is using it to magically summon Anja. Although nothing harmful happens, it still makes me think—how will Thelma use her power? What would she do if Anja wanted to leave her? Will Anja even have a choice? And finally, is the life Thelma lives now real, or is it a bubble of illusion she has created for herself?

But in a way, we all create our lives. We struggle against our share of repression and we can cause damage while trying to deal with it. If leave all the supernatural stuff aside, maybe we can make the miracles too, if we choose to trust ourselves more and accept who we truly are.