Released in 2007, the documentary was compiled from over two years of footage by a filmmaker using the pseudonym blackANDwhite, as Lynch embarks on the filming of Inland Empire. Titled Lynch (one), it was intended to be followed by two more films. In fact Lynch (Two) appeared as an extra on the Inland Empire DVD, and Lynch (Three) ended up becoming The Art Life. It’s not exactly clear as to who did what on these three films, but it at least seems clear at least that the interviews in Lynch (one) are by Jason Scheunemann, otherwise known as blackANDwhite, who had been acting as Lynch’s assistant for some time previously. Jon Nguyen, credited as a producer on Lynch (one) is a director of The Art Life and seemed to be the main driving force behind that production as well as a producer of Lynch (one), yet Jason S. is credited as cinematographer, so we can assume he did much of the filming, if not the interviewing.

All this mystery and confusion pairs well with a documentary about Lynch, and especially well with one that covers the production of possibly Lynch’s most challenging and critically divisive film so far, Inland Empire.

The documentary begins with a cold open, mid-conversation between Lynch and Jason, as Lynch records one of his then regular videos for lynch.com members, consisting of a weather report followed by the rather odd warning: “Whatever you’re thinking, Bastille Day is still a month away.” We get to see more of Lynch’s Bastille Day obsession throughout the film, but it’s not really explained. Roll Credits. It’s a suitably jarring opening to a documentary about Lynch, and these stylistic touches are scattered throughout. It’s a little like Lynch made a documentary about himself, which some people speculated at the time was a possibility.

“David is the only filmmaker that I have worked with, so my frame of reference is quite limited. It would seem only natural that David would influence my style. It poses a difficult and interesting challenge for me to not be accused of mimicking David. Many of the same things that interest David also interest me, but his approach to these things is entirely unique.” [1]

There is a mix of black and white and colour footage, with the picture quality not being the best which is somehow fitting given the criticism Lynch received for the quality of Inland Empire itself where his use of a relatively cheap DV camera was perhaps challenged by his penchant for very low lighting in dark dingy locations.

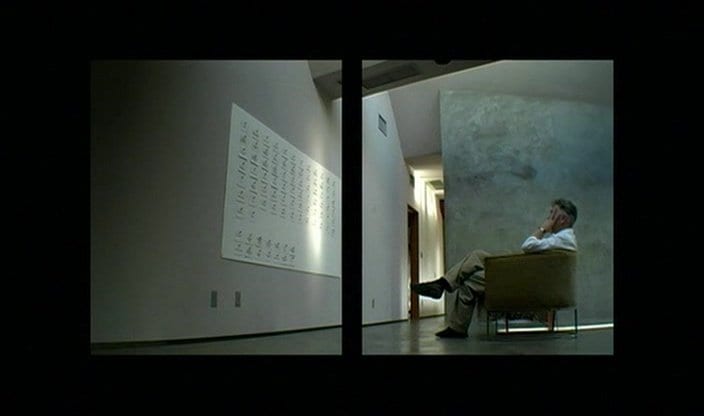

There is candid footage of Lynch going about his daily business, be that painting, sawing plaster cows in half, or recording for his website, interspersed with Jason interviewing Lynch in his office-cum-studio, which looks a bit like he might be squatting there, cigarette butts and debris all over the floor. Often Lynch launches into stories about his life, or things that affected him, like an entertaining Grandpa at Christmas. One he recounts with particular glee is when he came across a bloated cow corpse and spent half an hour trying to pop it with a pickaxe. The laughter of the interviewer is tinged perhaps with a slightly troubled note, as if he’s not sure he should be laughing at this, but wants to keep Lynch talking.

In many ways Lynch (one) feels like a trial run for the more polished product that is The Art Life, but focused less on his development and practice as an artist and more on the process of moviemaking. It is possibly more of an interesting feature to to watch because of it’s own stylistic devices and techniques as opposed to the more sedate yet prettier to look at successor.

“I approached the film from the standpoint of feeling. If i did not feel a clip it did not make it into the film. I wanted to give the people the feeling of what it was like to be around david, the thoughts that he makes you think, the avenues your creativity goes down.” [2]

Lynch talks about his time in Philadelphia, and the Transcendental Meditation that he has practised for decades, and how he believes it allows artists to dive into an ocean of pure creativity — something he often talks about. We get a glimpse of the kind of things that interest Lynch and the images that grab his attention. He talks of seeing an old french film in which a white horse appears breathing steam into a cold night which is then slaughtered, blood spraying everywhere.

Much of the documentary follows Lynch as he prepares for and shoots Inland Empire, which he reveals began with a suggestion from Laura Dern that they needed to ‘do something’ together. We follow Lynch as he tours disused Polish factories yelling “Hello Sally!” into their echoing dark bellies, presumably to check acoustics, and not simply because he enjoys shouting weird stuff in strange locations, but you never know.

He talks about the use of darkness and mood while photographing a factory in Poland on a location scouting expedition, and becomes quite animated when reviewing his shots of rusting machinery and faded peeling walls, pointing out in particular a photo he took of an ominous dank staircase which looks like it could very well be the seed of the staircase Mr C takes to get to the Dutchman’s in Season 3.

Throughout, you see similar evidence that Lynch ferrets ideas and images away that he’ll use later, sometimes multiple times, whether they’re relevant to the plot or not. There’s a glimpse of a suit jacket hanging to dry after being dyed a bright ‘Dougie’ green. We see Lynch recording via a boom mic stuck inside a gramophone horn the sound of him slowly winding the gramophone key, producing an eerie scraping and scratching noise, which we will see the development of at the beginning of Twin Peaks Season 3. Listen to the sounds…

In his use of repeated imagery and focus on symbols, textures, lighting and moods rather than coherent plot you can see that he really crosses the line between film-maker and artist, and has little distinction between the two, or much concern for the established rules of either form. It’s particularly evident in Inland Empire, which was largely a solo effort and sprang from the depths of his mind with little influence from anyone else — the first movie since Eraserhead that Lynch has had complete control over — directing, editing, writing, cinematography, and sound design. Whilst wildly different, you can see the artistic vision linking Eraserhead and Inland Empire, and whether you believe Lynch benefits from having collaborators reining in some of his impulses it is fascinating to watch him work.

One of the main takeaways of this documentary is Lynch’s incredible attention to detail in all aspects of production, perhaps best displayed here when we see him crawling around on a floor rubbing paint on it, trying to get the texture and patterns looking exactly how he wants it.

It is overall a fascinating insight into the man, the production of Inland Empire, Lynch’s approach to movie-making, and how Inland Empire differed — being basically a collage of shooting scenes from the hip, and ideas he has as he’s going along. “It’s an experiment” he frets, somewhat depressed and anxious about what he’s doing. The film doesn’t shy away from the troubles Lynch had with the production and simply figuring out what he was even trying to make. He talks about how he’s reading the bible to get ideas, “To find out what this film is about. That’s what I did on Eraserhead.”

There is a particularly awkward scene where Lynch gets a call from Jeremy Irons who he is courting to appear in the film, and tries to explain about the character and the film, but fails miserably. Jeremy doesn’t seem to mind though and Lynch seems genuinely excited to have bagged Mr Irons.

It seems Lynch both enjoys but is equally terrified of working blind, and indicates that this is the first time he’s been completely winging it when he says “I’ve never worked like this before.” It is a credit to Lynch that he allowed this level of access, displaying the open chaos of the production of Inland Empire, and his own confusion over how to approach it, to be filmed and released. Despite often not having even a loose grasp on the totality of the film he is making, his vision for scenes when it does come through is definite and clear, and it’s that clarity that makes his work both hypnotic and unlike most other filmmakers working in recent years.

“I want a one-legged 16 year-old girl…I want a Japanese girl who’s Eurasian…like 23…I want a pet monkey, a spider monkey.”

[1] “Documenting David Lynch.” http://www.canon-europe.com/you_connect/july2005/davidlynch/

Original link defunct. As quoted by MacGuffin in post “Lynch One,” XIXAX Film Forum, January 04, 2007. http://xixax.com/index.php?topic=9423.msg238025#msg238025

[2] Dawson, Nick. “blackANDwhite, LYNCH.” Filmmaker Magazine. http://filmmakermagazine.com/1287-blackandwhite-lynch/