The Rocketeer may be a relatively young comic-book hero among those who have inspired movies, but the character has come a long way. Before the DC Extended Universe and Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, before the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, and the long-running X-Men series, seeing superhero movies on the big screen in the 1990s felt like indulging in a bite at your favorite fast-food chain about once a year. Now, it’s as if the chains have pushed most of your local independent restaurants out of business and you find practically nothing but fast food when looking for a place to eat. Watching superhero movies may not pose the same health risks as consuming an excess of French fries and milkshakes. One recalls Morgan Spurlock’s experiment eating at McDonald’s three times a day for a month, the effects of which he documented in the film Super Size Me (2004). I do sometimes wonder, though, what a steady diet of Marvel’s smug, quippy humor and oversaturation of CGI might do to a person.

Building a franchise involves creating an expansive narrative world through sequels, crossover storylines, and spin-offs in different media, and compared to today’s long-term planning for intellectual properties, Hollywood’s production of movies adapted from comics moved at a rather modest pace in the 1990s. After the massive blockbuster coup that Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) scored for Warner Bros., the first notable superhero feature since Superman II (1980), other studios followed suit with Dick Tracy (1990), The Rocketeer (1991), The Crow (1994), The Shadow (1994), Judge Dredd (1995), The Phantom (1996), Spawn (1997), and Blade (1998). Running between 96 and 120 minutes, they look quite lean alongside Marvel and DC’s elephantine epics. Of these titles, the only movies that led to sequels were Blade (with Blade II [2002] and Blade: Trinity [2004]) and The Crow (with City of Angels [1996], Salvation [2000], and Wicked Prayer [2005], the latter two released nearly direct-to-video). Sequels were primarily Batman’s territory, albeit sharing the thinnest of continuity, marked by Batman Returns (1992), Batman Forever (1995), and Batman and Robin (1997).

It isn’t only the sheer amount of superhero “content” in the twenty-first-century marketplace that renders these earlier movies quaint by comparison, but also their decidedly retro settings and approach. Dick Tracy and The Phantom originated in 1930s newspaper comic-strips, while The Shadow made his first appearance contemporaneously in the pulps and on radio before starring in his own comic-strip and comic-book series in the 1940s. Like Burton’s Batman, even the darker, more adult-oriented entries in this cycle—The Crow, Judge Dredd, Spawn, and Blade—seem indebted to the urban-nightmare vision of 1940s film noir.

The odd man out here is Cliff Secord (alias The Rocketeer), who neither possesses superhuman abilities like The Phantom and The Shadow, nor occupies a social position of power and authority like the respected police detective Dick Tracy. Moreover, the source material for the movie was not a vintage comic, but an indie comic-book series published between 1982 and 1984 that took place in the 1930s and its inspiration from Republic Pictures serials featuring Rocket Man and Commando Cody. Written and illustrated by the late Dave Stevens, The Rocketeer was also the least well-known comic to receive a screen adaptation from a major studio in the 1990s (its canonical status is more as a cult classic). While the movie versions of The Rocketeer (Disney), The Shadow (Universal), and The Phantom (Paramount) all underperformed at the box-office and therefore never launched the franchises their studios intended, The Rocketeer has steadily maintained an affectionate following over the past two decades. And with the 40th anniversary of the character’s debut in comics this year, the time is ripe for a larger audience to discover Stevens’s endearing creation.

The Rocketeer, the Comic

Set in 1938 Los Angeles, The Rocketeer tells the story of hardscrabble carny-turned-stunt pilot Cliff Secord, who happens upon the prototype of a top-secret jetpack (the “CIRRUS X3”) that has been stolen from its mysterious inventor. Cliff thinks the gizmo will be his ticket to fame and fortune, securing his future with his girlfriend Betty, an aspiring actress/model whom Stevens fashioned after the underground pin-up queen of the 1950s, Bettie Page. Soon after Cliff straps on the jetpack, wearing a mask that also serves as both a rudder and a protective helmet to become “The Rocketeer,” he has the F.B.I., Nazi spies, and the inventor’s aides on his tail—all wanting the CIRRUS X3 for their own purposes. The inventor’s aides, implied to be Lt. Col. “Monk” Mayfair and Brig. Gen. “Ham” Brooks, suggest that the inventor is none other than 1930s pulp-magazine hero Doc Savage.

Part of The Rocketeer’s relative obscurity as a comic has to do with its circuitous publication history. Then a newcomer to the comics industry, Stevens published the first two chapters as six-page backup stories in Starslayer #2 (April 1982) and #3 (June 1982). The publisher, Pacific Comics (PC), had a hit on its hands and promoted The Rocketeer to the lead story in the inaugural issue of Pacific Presents (October 1982), where the third chapter was backed by the introduction of Steve Ditko’s The Missing Man. Stevens’s reputation in the comics world was skyrocketing, having just won the first annual Ross Manning Promising Newcomer Award at the 1982 San Diego Comic-Con.

What PC lacked in size and a staff, it made up for in its unique benefit for creators: giving them ownership and control of their original work. However, between the laborious demands on Stevens for each chapter—he alone was responsible for writing, penciling, inking, and coloring—and his legendary perfectionism in his art and research, making The Rocketeer the monthly title that PC envisioned was simply unfeasible. He hadn’t even mapped out an arc for the character beyond Chapter 3. Continuing work on The Rocketeer as a passion project, Stevens earned a living by taking miscellaneous art jobs. Not until April 1983 did the fourth chapter appear in Pacific Presents #2, backed again by The Missing Man. By the time he submitted his fifth and final chapter to be published in Pacific Presents #5, the company shuttered. Another independent press, Eclipse Comics, picked it up and published it under the title The Rocketeer Special Edition #1.

In September 1985, Eclipse published a collection of all five chapters titled The Rocketeer Graphic Album, which included an introduction by sci/fi author Harlan Ellison. The following year, the book won a Jack Kirby Comics Industry Award for Best Graphic Album and the San Diego Comic-Con’s Inkpot Award. It was around this time that Stevens actively pursued turning The Rocketeer into a feature film.

Unwilling to give Eclipse the rights to publish subsequent Rocketeer comics, Stevens moved to a third independent press, Comico. While developing a new run on The Rocketeer that would continue the 1982-1984 story, he met screenwriters Danny Bilson and the late Paul De Meo, who shared his fondness for interwar-American popular culture and used to frequent Golden Apple Comics in Los Angeles (they went on to adapt The Flash for CBS [1990-1991]). As admirers of Stevens’s comic, they saw potential for capitalizing on the phenomenal success of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and in 1987, the team signed with Disney to make The Rocketeer, the movie. In July 1988, Comico published The Rocketeer Adventure Magazine #1 with the first story in the new comic-book arc. Stevens then brought Bilson and De Meo on board to co-write the story for The Rocketeer Adventure Magazine #2, published in July 1989. Publication on the series stalled yet again when Comico went bankrupt. The movie, however, was underway, a big-budget, lavishly produced spectacle with Stevens in the background as a consultant and co-producer, George Lucas’s Industrial Light & Magic handling the visual effects, and Joe Johnston directing Bilson and De Meo’s script (Johnston more recently directed Marvel’s Captain America: The First Avenger [2011]).

Reteamed with Bilson and De Meo, Stevens belatedly concluded the comic-book story at Dark Horse, his fourth publisher, which issued The Rocketeer Adventure Magazine #3 in January 1995—four and a half years after the movie’s release. Disappointed with the sales of such an expensive comic to produce, Dark Horse chose to discontinue The Rocketeer, although in September 1996, it did publish a collection of the three Rocketeer Adventure stories under the title The Rocketeer: Cliff’s New York Adventure. Here, Cliff follows Betty to New York City and learns that the surviving members of his former carnival troupe have been murdered, one-by-one, by an unknown killer. New characters are clearly meant to remind readers of The Shadow, Tod Browning’s horror classic Freaks (1932), and monster-movie actor Rondo Hatton (Bilson and De Meo had already introduced a Hatton-esque heavy in the movie and reincorporated him into the comic’s second and third chapters). The ‘90s nostalgia bubble for the Golden Age of comics and Hollywood genre movies, it would seem, had officially burst.

Still, the first life of The Rocketeer is not without a bittersweet ending. The comic helped revive the popularity of Bettie Page in the 1980s, but she had long since retired after becoming a born-again Christian and disappearing from the public eye. Suffering from serious mental health issues, Page had been sentenced to Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino County for ten years after assaulting her landlady. Disney insisted on changing the name “Betty” to “Jenny” out of concern that, without the right of publicity, Page might reemerge and sue the company. Not long after her release in 1992, she met Stevens. As it turned out, they were practically neighbors. By this point, Page was in her seventies, but she and Stevens formed a close personal friendship, and he saw to it that she was retroactively remunerated for the use of her likeness (both others’ use and his own). In addition to spending time with her socially, Stevens would deliver her groceries, drive her to appointments, and take her out in public. The two remained friends until Stevens’s death from hairy cell leukemia at the age of 52 on March 11, 2008, nine months to the day before Page’s death at 85.

The Rocketeer, the Movie

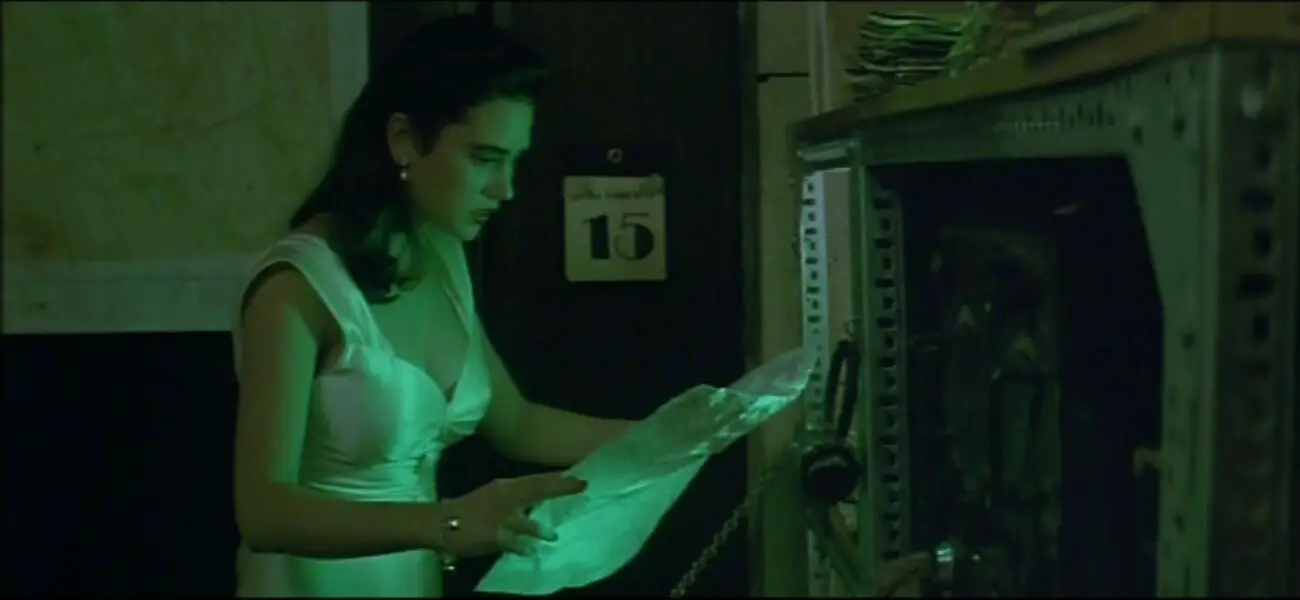

On June 19, 1991, The Rocketeer premiered at the El Capitan Theater in Hollywood and entered wide release on June 21 to generally positive if not exactly rave reviews. The enormous promotional apparatus included a comic-book adaptation of the movie, novelizations, a video game for the Nintendo Entertainment System, pin-back buttons, and tie-ins with Topps, Pizza Hut, and M&M’s/Mars. Of course, there’s no substitution for Stevens’s exquisite artwork, but the movie is equally meticulous and evocative in its own ways, making use of period-specific costumes and production design (those Art Deco interiors!), stylized lighting reminiscent of comic-book color schemes (those electric purples and greens!), an anthemic score by James Horner, and a pair of beautiful, lovable leads (Bill Campbell and Jennifer Connelly, not yet stars, somehow look as if Stevens had them in mind when he drew his main characters!).

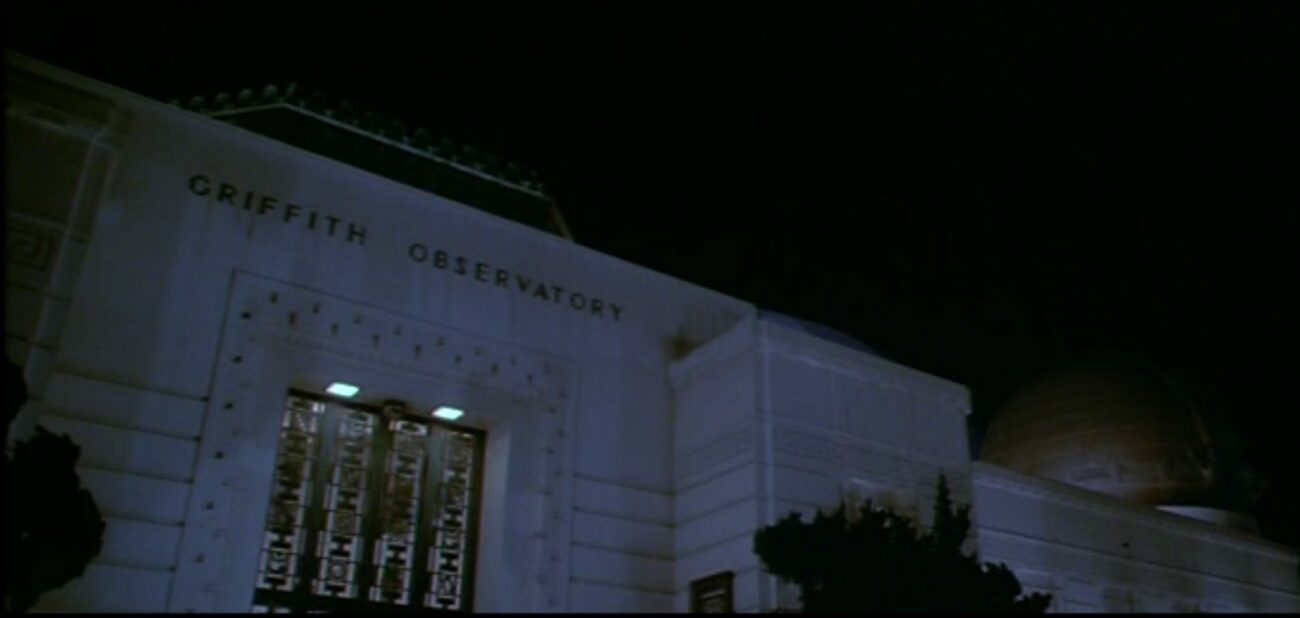

Director Joe Johnston seamlessly blends 1930s Los Angeles history with pulp fantasy, inserting locations both real (the Griffith Observatory, the Ennis House) and imaginary (the South Seas Club), while borrowing the Bulldog Cafe from Stevens’ comic in a nod to the Programmatic-architecture craze at the time (an actual café shaped like a bulldog, smoking a pipe, operated in Los Angeles from 1928 to the mid-1960s). Co-stars Alan Arkin (as Cliff’s irascible older pal Peevy) and Paul Sorvino (as gangster Eddie Valentine, a new character) would have been right at home among Hollywood’s B-movies and character actors of the studio era. Watch closely and you’ll spot “cameos” by Groucho Marx, Clark Gable, and W.C. Fields, as well as the Bette Davis melodrama Jezebel (1938) premiering at the recreated Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

Instead of Doc Savage, the designer of the stolen CIRRUS X3 is Howard Hughes (Terry O’Quinn), but G-Men and Nazis are still after Cliff for it. Matinee idol Neville Sinclair, the chief villain played by a wonderfully caddish Timothy Dalton, did not in fact exist, nor did his movies The Laughing Bandit and Wings of Honor. As an actor spying for the Nazis, though, he may remind cinephiles of Charles Higham’s controversial characterization of Errol Flynn. Higham’s 1980 biography Errol Flynn: The Untold Story posited the unsubstantiated claim that the swashbuckler-star performed the same nefarious role during World War II.

Not enough credit goes to Bilson and De Meo for adapting Stevens’s romantic subplot centered on Cliff and Betty’s always-out-of-sync relationship, which Campbell and Connelly make surprisingly poignant on the screen as Cliff and Jenny, née Betty, respectively. Cliff and Betty/Jenny are entirely believable as plucky yet vulnerable, flawed yet fundamentally decent kids. Their problem is that they both love each other, but don’t know how to show it—partly because they both can be selfish, even opportunistic, in pursuing the seemingly incompatible lines of work that drive them. In the comics, Cliff rightfully holds contempt for the predatory men and “booshwah” elitism of Hollywood. Wary of Betty’s rather naïve awe of celebrities, he also confuses her career ambitions with a desire for the economic comforts he cannot provide. Betty, meanwhile, sees Cliff as possessive and sometimes reckless, having grown tired of worrying about his safety as a stunt pilot.

The movie softens the characters slightly, recasting Cliff as less of a jealous, mistrustful type and Jenny as more girl-next-door Gene Tierney than subversive sexpot Bettie Page. The conflict here is that each fears rejection from the other. As Jenny misses Cliff’s races and test flights while at auditions and on set, Cliff thinks she is wasting her time as an extra and unfairly assumes she prefers the company of her “Hollywood crowd […], talking about movie stars and night clubs.” “I want her to think I’m makin’ something of myself,” he tells Peevy, “not that I’m just an out-of-work pilot with holes in his pockets.” When Jenny learns of his latest accident at the airfield, she mistakes his avoidance to tell her as a sign of his emotional detachment. “I don’t want you to be sorry, Cliff,” she says. “I want you to stop treating me like a stranger. When something goes wrong, I should be the first one to know about it. I shouldn’t be the last.” If The Rocketeer pays homage to the comics, pulps, radio shows, and cliffhanger-serials of the past, it also improves on a familiar formula. How many relationships in those stories seemed human enough to care about?

The Rocketeer is the first movie I remember watching in a theater, and it has a bigger heart, a greater sense of joy and wonder, and more sprezzatura than any superhero movie I have seen since then. For all of its intertextual play, it is never arch or glib, but completely earnest and edgeless as an adventure movie. Johnston, Bilson, and De Meo take the characters and story as seriously as Stevens without resorting to “dark, gritty” cynicism to prove it (“grittiness” being the presumed alternative to jokey irony and the edict that neither the characters nor the audience should be having any fun). Thankfully, in 1991, superhero movies had not yet become invested in tediously labyrinthine mythologies, and it was perfectly acceptable for The Rocketeer just to be about fighting Nazis. Watching the movie thirty-one years later, I could wish for nothing more.

The Rocketeer‘s Afterlife

Following Stevens’s death, IDW Publishing released The Rocketeer: The Complete Adventures (2009), with lush recoloring by Laura Martin, and an oversized “deluxe edition” (also 2009) that contained supplemental material. In 2011, an “artist’s edition” was published, comprised of high-resolution color scans of Stevens’s original art, allowing readers to see Stevens’s notations, white-out marks, the gradients in the ink, and so forth. The book won Eisner Awards at Comic-Con International for Best Archival Collection/Project for comic books and Best Publication Design, and is scheduled to come back in print later this year along with the “deluxe edition.”

Between 2011 and 2016, IDW also published a new Rocketeer comic-book series, starting with eight short-story issues titled Rocketeer Adventures (2011–2012), collected in two volumes and eventually a complete “deluxe edition,” that boasted an abundance of different contributors. The series continued with four full story arcs: Mark Waid and Chris Samnee’s The Rocketeer: Cargo of Doom (2013), in which Cliff battles dinosaurs loose in L.A.; Roger Langridge and J Bone’s The Rocketeer vs. Hollywood Horror (2013), pitting Cliff against a Lovecraftian mad scientist; The Rocketeer & The Spirit: Pulp Friction (2014), a crossover storyline that brings Will Eisner’s The Spirit into Stevens’s universe; and Marc Guggenheim, Dave Bullock, and J Bone’s The Rocketeer at War (2016), set at the beginning of the U.S. intervention in World War II. IDW even published a collection of pulp-style prose stories titled The Rocketeer: Jet-Pack Adventures, edited by Jeff Conner and Tom Waltz, with illustrations by J Bone.

Earlier this year, the character returned to comics with IDW’s The Rocketeer: The Great Race by Stephen Mooney and Len O’Grady, published in conjunction with the 40th-anniversary of Stevens’s comic. The celebration has included a Rocketeer panel and the premiere of the documentary Dave Stevens: Drawn to Perfection at the San Diego Comic-Con, an exhibit at the Comic-Con Museum, and the release of new, officially licensed collectibles. At the risk of offering too much of a good thing, the Rocketeer Renaissance may not be over yet. Producers David and Jessica Oyelowo, and writer Edward Ricourt, are currently developing a legacy sequel to the 1991 movie for Disney+, focusing on a retired Tuskegee Airman who takes up the well-worn jetpack. For young audiences of a certain age, it will be their first movie-theater memory. Assuming Disney gets it right again, I will envy them.

Works Consulted

Bilson, Danny, and Paul De Meo. “Pro2Pro: Rocketeer-ing Its Way to a Theater Near You!” By Jerry Boyd. Back Issue, no. 47 (April 2011): 58-64.

De Meo, Paul. “Writer/Producer: Paul De Meo.” By Dan Hagen. Comics Interview, no. 89 (1990): 4-18.

Mao, Kelvin. “Dave Stevens: An Oral History of The Rocketeer.” The Rocketeer: The Great Race, April-July 2022.

Stevens, Dave. “Interview: Dave Stevens: One Last Conversation.” By Kelvin Mao. Back Issue, no. 47 (April 2011): 30-57.

—-. “Writer/Artist: Dave Stevens.” By Jeff Gelb. Comics Interview, no. 97 (1991): 4-33.

Stout, William. “40 Years of The Rocketeer.” Comic-Con International: San Diego, July 2022.

“The Rocketeer Adventure Magazine.” Amazing Heroes Preview Special, no. 145 (July 1988): 192-194.

Thanks so much, Billy (if I may). Needless to say, this is one of the highest compliments I could ever expect to receive on such an article. My eight-year-old self would never believe it.

A lovely article, Will, couldn’t agree more. I too adore the film, and am sure I would even if it weren’t an actual part of my life.