We’re no doubt all familiar with the expression: “it’s not the destination, it’s the journey” and it’s one that is often applied to films. See more than a handful and by the end of a movie’s first act, you’ll know what point it’s driving at, what it’s trying to say. It’s not what films are about but how they’re about them it makes them rewarding. However, there are some exceptions. A bad ending can easily poison the memory of an enjoyable journey, and make it all look like a waste of time in retrospect. More fascinating though are the examples of films you weren’t enjoying, films you found boring or irritating, until the very end, when something happened that put a fresh perspective on things, that made you realise, “wow, that was worth the journey!”

These movies can sometimes be more rewarding than those you were enjoying from start to finish. After all, if you lose your audience, it takes something pretty impressive to win them back around by the time the credits roll. These are the kinds of films we’ll be taking about today, and I’m sure you’ll have your own. They might not be irredeemable or bad prior to the ending, but they’re movies that wouldn’t really have been anything all that special until then. These are the movies that prove why you should never leave a film unfinished, there’s always time for a movie to surprise you!

Obviously, there are major spoilers ahead, so scroll with caution!

Dogville (2003)

If films like those on this list have taught me never to walk out of a movie, Lars Von Trier is probably the filmmaker who’s benefited the most from this policy. Though I consider the great majority of his work to be, well… junk, there’s always that off-chance he’ll make something of real merit. The reason I kept giving him chances long after I should have given him up as lost, is that when I first came to write this list, Dogville was the first film I thought of.

For much of it’s runtime Dogville fits firmly into the mold of Von Trier’s “Golden Heart” films, these being films about women who want nothing for themselves and only wish to secure happier futures for the ones they love, and who are abused and rejected by society at every turn. These films have been variable and controversial, but for my money, Dancer in the Dark is a masterpiece, my favourite musical and just the saddest film ever made, rescued from despair only by its own brilliance leaving one so enthused with the potential of the medium. However, Dogville spends the great majority of its runtime doing more or less the same thing, but without any of the exuberance or heart.

The film introduces us to the town of Dogville, and to Grace (Nicole Kidman) a desperate young woman who arrives in need of shelter and protection. The townsfolk admit her, on condition she pull her weight, before gradually burdening her with more chores. Their collective treatment of her becomes increasingly sadistic and inhumane, reducing her first to a servant and then a slave.

With the drama unfolding entirely upon a sound-stage with only the barest of props and sets drawn on the floor, Dogville is as pure a Brechtian exercise as you’ll get, leaving you only with the spectacle of a blameless young woman being exploited, abused, tortured and raped for two hours. There’s nothing to focus on except the bare bones of the story being told, and it’s one he’d already spent a whole trilogy telling and retelling. Yes, it’s all an allegory for America and the way that the supposed utopia actually treats the tired masses yearning to break free who come to it in need, but surely you don’t have to subject us to the spectacle of a person being fictionally brutalised for two hours to get that point across? It’s an excruciating and infuriatingly pointless watch.

That is, until the third act comes along and James Caan rolls into town. It transpires that Grace is in fact, no innocent, vulnerable waif on the run from the authorities, and the citizens of Dogville have in fact been appallingly mistreating the runaway daughter of a cold, ruthless crime boss. Finally, after four movies, the Golden Heart is empty of charity and filled with wrath. Grace unleashes her righteous vengeance on the town, her father’s men sparing no one but the dog. It’s shallow and horrifyingly pessimistic, but no matter how forgiving and charitable you are in real life, von Trier just spent two hours putting you in the worst possible mood he can. Yes, you’re a bit disgusted with yourself, but you can’t deny the part of yourself that yearns for justice, and a malicious grin creeps its way onto your lips, as the residents’ cruel, callous, selfish, spiteful, jealous, bullying, lecherous actions come home to roost. The point about America’s hypocrisy is made, but you still get to experience one of the naughtiest and most cathartic endings in cinema history.

And Then We Danced (2019)

To return to that proviso that these movies wouldn’t be bad if not for having such great endings, but that they wouldn’t be anything remarkable, And Then We Danced is for the most part an intriguing but kind of slow and uninspiring coming of age movie. Queer Cinema is replete with examples of characters pulling at the reigns of their culture and many of these characters journeys play out similarly. The challenge in telling such a story is to use the specificities of your particular culture to tell the story in a way that feels uniquely revealing. Critically re-evaluating the products and practices of your culture, taking what’s worthy about them and reappropriating them for the cause of sincere self-expression and freedom.

With so few exceptions that I can’t currently think of any, cultures always seek out ways to suppress, problematise and demonise sexuality, especially non-heteronormative sexualities. Georgian society is no different, and one of the many, many ways in which that homophobia expresses itself is in the character of Georgian national dance. Homophobia of course has its roots in misogyny, male society detesting femininity and abjuring its expressions outside of its allotted social role. As we are told early on in And Then We Danced, Georgian national dance is rigid, traditional, sober, a ritualistic performance of national pride, one with no room for personal expression, sexuality, or anything but the most strictly defined gendered archetypes.

This is the world Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani) is trying to break into after his parents, grandparents and older brother failed to make names for themselves in it. He’s on a long road that might possibly lead him to the acclaim of the establishment, but his dancing is just a little too effeminate to make the grade and he’s working hard at the dance academy to overcome this final obstacle. To put it in American film terms, he’s having the same and opposite problem to Nina in Black Swan, he’s not rigid and chaste enough but he’s also too weak. His Lily shortly arrives in the form of Irakli (Bachi Valishvili) a handsome, confident and effortlessly gifted would-be rival with whom he begins to bond, and in whose fun and freeing company he may just find the answers he doesn’t know he’s looking for.

It’s a very familiar story and for the majority of its runtime, And Then We Danced tells it in a fairly dry way that’s not particularly inspiring. The challenge with dance movies is to make a dance as revealing as a dialogue scene. To those well versed in dance, interpreting such a scene may be easy, but to those uninitiated, making such a moment accessible in the way a night at the ballet most assuredly isn’t, is the very touch cinema, used correctly, might bring to the raw performance. It’s a rare feat and therefore a high compliment to say that as sensitive and engaging as the story here can be, the standout scenes are all dances and the best by far, and the sequence that brings the whole film together, is the final, rapturous audition piece.

After a grueling preparation that has taken all he has, Merab is finally faced with an opportunity to join the country’s most prestigious ensemble. He’s working on a badly injured ankle, but he’s not missing his shot to prove himself. As his judges expect and demand, he begins to dance with forceful, stiff dramatic movements, but then, he comes down badly from a leap, straining his injured ankle. He recovers and perseveres, continuing to dance on his knees! His impressive resolve notwithstanding, he knows he’s lost the panel, they don’t like him. And so, after two hours of buildup, without missing a beat, his efforts to please turn into an act of defiance. He throws himself into his dance, he becomes himself, dancing in playful sashays and twirling leaps, arcing his back and rolling his head on his neck. He rests his fingers on his cheeks and moves his feet in hesitant, coquettish steps. His limber, lingering, sensuous moves incense the judges, one of whom storms off in a rage.

In the space of a few seconds, Merab loses the Georgian dancing establishment’s respect, and it loses his servitude. He bows, and walks out as his own man. It’s a thrilling, joyous moment of cathartic rebellion that comes at the end of a very straight-faced, well behaved film about emotional and sexual repression. It’s the perfect ending that makes the often sluggish journey entirely worth it. The dancing is astonishing to watch, displaying a level of accomplishment that can only be achieved through a level of dedication that can only necessitate the eclipsing of the innocent love of dance that it articulates. This film is about rediscovering that love and celebrating that itself. It’s a fantastic, emancipatory and populist answer to a film like Whiplash or The Disciple whose characters are so burdened with the expectation of perfection. These three films would make an intoxicating triple bill, one a visceral horror movie about when the pursuit of greatness goes too far, one a mature, somber rumination on the concept and the last a liberating, clear-eyed, idealistic and compassionate coming of age tale. The preceding two hours of And Then We Danced has meaning of it’s own, but really, it is all preamble to the final scene.

The Devil All the Time (2020)

To say that The Devil All the Time is saved by its ending might be a bit of an exaggeration as I still don’t like the movie. But the only part I do like is literally the last thirty seconds and it does throw a new light on the film that preceded it, to the point that I at least got something out of the whole. It was one of those eureka moments, but not quite strong enough a one to erase the irritation and boredom of the more than two hours that preceded it.

I’d gone into The Devil All the Time with high hopes, Antoino Campos’s previous film Christine is genuinely one of my all time favourites, and certainly one of the most underrated films in recent memory. You know that Oscar Rebecca Hall doesn’t have? Yeah, she should’ve won it for Christine. And look at the cast Campos assembled for this: Robert Pattinson, Riley Keough, Bill Skarsgard. Harry Melling, Mia Wasikowska, Eliza Scanlan, Haley Bennett, Sebastian Stan, and Tom Holland as well! How could this not be great?

What The Devil All the Time offers is a series of interconnected vignettes, telling stories of people who are innocent and people who are evil. However, which group any individual belongs to will vary relative to their situation and company. The deranged, confused and murderous religious zealot may seem like a lamb before the young couple who enjoy ritualistically slaughtering young men for their photographic kicks.

There are aspects to the film I do still think are outright bad, chief among which being Robert Pattinson’s overripe performance as predatory Pastor Preston Teagardin. This is a rare film where I think almost every cast member was to one degree or another miscast but he’s the worst offender. You’d think he’d have learned from The King not to take on any more heavily accented villain roles. I was also frustrated to see Riley Keough wasted yet again in another role unworthy of the talent she displayed in her breakthrough performances. At least it’s not as bad as The House That Jack Built.

The biggest issue is that the stories told in the first half aren’t interesting in themselves, feeling more like rejected pitches for an episode of American Horror Story (I don’t know, I’ve never watched it, insert a more appropriate comparison if you like) that were never taken beyond their basic summary. You can tell the film was based on a book because this is the sort of material books include, while screenwriters are taught to take out as irrelevant. Eventually these irrelevancies, although it would be generous to say they ‘pay-off’, do at least form a foundation for a single poignant moment. I’m almost of the opinion that the first hour and a half being so empty and disjointed was intentional. I say almost, because it’s a very dim filmmaker who intentionally makes a boring film to make a statement. Especially when such a statement didn’t need a boring film to make it, which I don’t think this film did.

After more than an hour of tedious buildup we do finally arrive at something approaching a narrative, though even that is a raw, undercooked and uninspired thriller plot-line that hardly justifies half the time it takes to tell. Yet as the film enters its final minutes it takes on a more reflective tone, and the faintest mist of purpose condenses. The film has spent the last two and a half hours painting a portrait of a generation of American youth. One raised by dissolute parents scarred by war and disaffected with church and home. A generation put through hell and left to look optimistically ahead, to a potentially brighter, but likely no better, future.

In the final minute, our young, battle-scarred protagonist Arvin Russell (Tom Holland) stumbles out of his home town, nothing but bodies behind him, and flags down a ride. The vehicle that stops is not one of the ramshackle pickups or claustrophobic station wagons we’ve seen so far in the film, but a Volkswagen van, it might as well be the Mystery Bus. The message is clear, the ’60s have arrived, and as young Arvin climbs into the passenger seat and rests his head on the window to get some long overdue shut-eye, he’s swept on into the future. A future of change, Vietnam, Watergate, Civil Rights battles, everything Forrest Gump lived through, except, Arvin’s experiences will likely be a lot more unsentimental and a lot less forgiving. Whatever my issues with the rest of the film, I do genuinely love the note it ends on. I still didn’t like The Devil All the Time, but I was at least able to say that I finally understood The Devil All the Time.

Rec (2007)

I think it’s underappreciated how far Danny Boyle’s high intensity editing aesthetic went to maximising the impact of his fast, virally originating zombies back with 28 Days Later, because I can honestly say I don’t think I’ve been scared by a fast zombie in a movie since. The performances are always so goofy when looked at with a level gaze, like most monster effects, you don’t really want to give the audience too many clear looks at the beast. You want to keep the reality—an actor covered in fake blood flailing and gnashing at the camera—at as much of a distance as you can engineer. There’s many recent zombie movies where I found the zombies more laughable than scary.

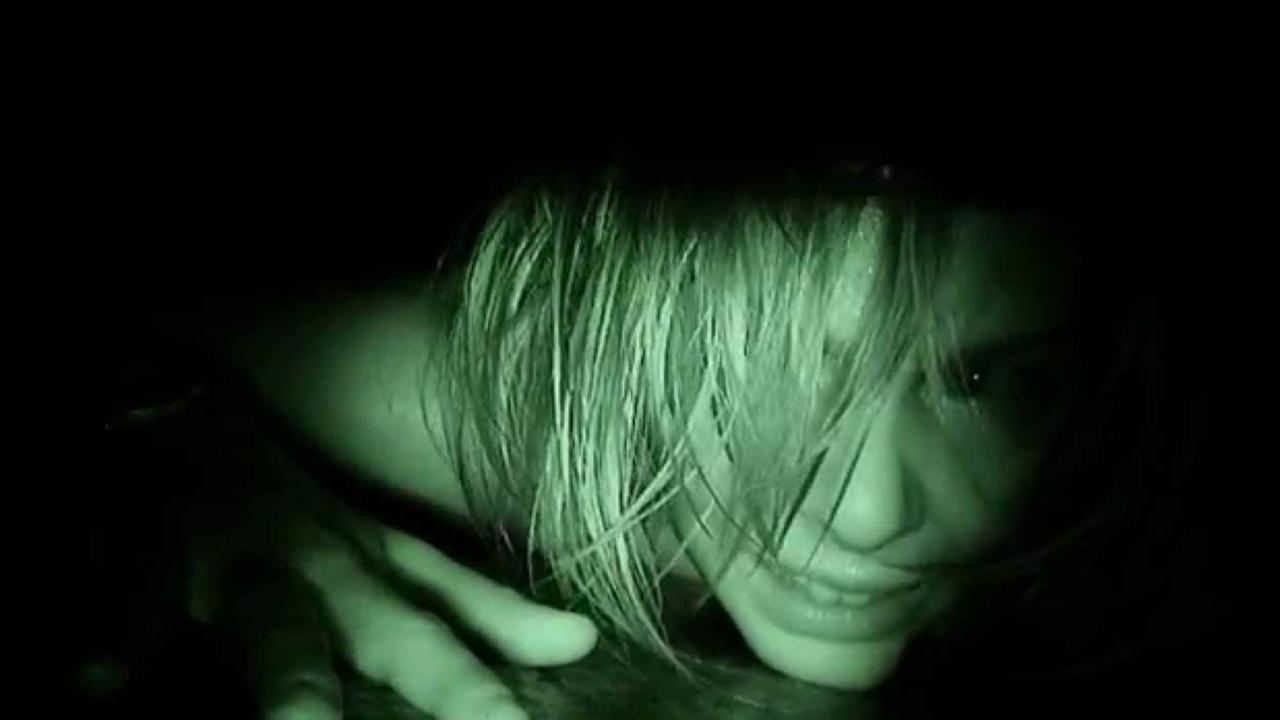

For the majority of its runtime, Rec is one of these movies; a more or less completely generic found footage zombie horror movie. The film follows its reporter protagonist as she shoots a late night docudrama following a fire crew around for the night, their first call being to provide assistance to an elderly woman who has locked herself in her apartment. From there, zombies happen in predictable fashion and it’s pretty lifeless, awkward and by the numbers. That is, until the last ten minutes. As the building is sealed off and each of the apartment building’s tenants falls victim to the outbreak, the reporter and her cameraman are driven higher in the building, eventually arriving at what they believe is the one remaining safe refuge and escape route: the attic. However, the attic transpires to in fact be the epicentre of the outbreak, with the building having been the site of a doctor’s experiments on demonic possession.

The infa-red point-of-view camerawork throughout this scene predicts the style of modern survival horror video games as the last two survivors are stalked through the pitch-dark attic by the patient zero, a skeletally malnourished woman believed to be possessed by the devil. It’s an inspired shift in tone from zombie action horror to pseudo religious supernatural horror and a brilliant intensification of the scenario, contracting the situation down to a couple of darkened rooms. Its impact is lessened today as we’ve seen this kind of scenario play out a lot in the years since, but it’s still a terrific ending that delivers all the scares the preceding seventy or so minutes had been sorely lacking. For a thoroughly mundane movie, Rec manages to pull a genuinely terrifying climax out of the bag at the last moment.

The Dead Don’t Die (2019)

One of the most anticipated movies of 2019 swiftly turned into one of the year’s most negatively received, when Jim Jarmusch’s star studded zombie dark comedy was released and met with an overwhelming: ‘what the hell is this!?’ Therefore, my curiosity going unreinforced, I let the movie lie for a while until I had a spare afternoon and it came up on Netflix. As it is, I don’t think The Dead Don’t Die is a bad movie, though I see the confusion as I do struggle to call it a good one.

What it is is a deeply absurdist and extremely deadpan take on the zombie apocalypse. That absurdism is not just an aesthetic or tonal choice, it’s a defining theme of what is arguably, underneath the arch comic monotone, Jarmusch’s darkest and most nihilistic film. It doesn’t feel misanthropic though, there’s a sense of affection and therefore tragedy in the inevitable downfall of civilisation, largely brought out of Bill Murray’s melancholic presence. The Dead Don’t Die is a rare zombie movie that presents the end of the world as kind of what it would be: a shame, an awful pity… unfortunate.

Despite the dry comic sensibility, it remains downbeat and cycles through zombie-movie tropes with mechanical indifference. The movie itself is zombie-like, clicking off its characters with a sense of obligation. It’s rarely funny, though it might occasionally raise a smile, and it’s main purpose is actually an exceptionally pessimistic critique of society and humanity as a whole, wandering blindly into catastrophe. They’d be worth saving, but it’s not as if you really could.

The film follows the residents of the small town of Centreville as polar fracking causes the dead to rise from their graves and kill the living, adding them to their witlessly shambling, soulless ranks, leaving the town’s small Sheriff’s department Cliff (Bill Murray), Ronnie (Adam Driver) and Mindy (Chloe Sevigny) to half-heartedly and directionlessly make some token effort to stem the tide. Some of the cast seem to be having some kind of fun: Tilda Swinton as the Scottish samurai mortician gives the fruitiest performance, Steve Buscemi plays a clueless racist farmer, and Tom Waits acts as Greek Chorus as a misanthropic woodland hermit observing proceedings through his binoculars.

Mostly though, the humour and attractive cast are only there to keep proceedings from becoming desperately depressing, enabling the film to raise a dejected gallows smirk instead of outright despair. The film includes several fourth wall breaks that add to the film’s sense of detachment, with Adam Driver’s character’s pessimism ultimately justified by his revelation that Driver was sent the complete script, while his co-stars were only sent their own scenes. I think the film’s secret weapon ends up being Sevigny and Murray, who are permitted to instill the right level of humanity and pathos into their roles to keep the whole thing from feeling overly misanthropic. There’s just that touch of poignancy and human feeling that keeps the tragedy in downfall of humanity, despite the film’s deadpan, dismissive tone.

It is generally a fairly dull film and I don’t intend to make it seem more profound than it actually is. The film just kind of wears you down into finding something meaningful to grasp onto and in my view it did kind of succeed. It’s not a film I can wholeheartedly recommend, but I do think there is something sort of genius about where it leaves you by the end, with it’s matter of fact “make-you-think” approach to theme achieving a kind of cumulative effect. It’s shrugging indifference and lack of resolution is the best way to convey it’s absurdist philosophy. By the time its heroes bite the dust, you do feel a genuine sense of sadness. The journey is often less than scintillating though and yeah, that is sort of the point.

High Tension (2003)

High Tension (a.k.a. Switchblade Romance) is a routine appearance on the exact opposite sort of list and was perhaps the last film some of you expected to see here. The consensus seems to be that this is a potentially great slasher movie, stupidly undermined by a preposterous and insulting twist that cheats the audience. I completely understand this perspective; however, I personally love the ending to High Tension. For those who’ve not seen it, the movie follows Marie (Cecile de France) and Alexia (Maiwenn), two best friends on a trip to stay with Alexia’s middle class family in the country. However, as night falls and Marie is just getting down to some private time, the house comes under attack from a perverted serial killer (a fantastically inhuman Philippe Nahon) who brutally slaughters Alexia’s family and abducts her, leaving Marie to save the day and rescue her friend from the murderer’s clutches.

However, once she finally succeeds in defeating the mysterious killer, the film’s shock revelation arrives. Marie was the killer all along and we’ve been sharing in her delusional version of events. She’s obsessively in love with Alexia and killed her traditional family to have her all to herself, projecting her homicidal desire for her friend onto a violent male monster. Some might say this twist is incredibly stupid, because you know…it is. But this is a movie where a man’s head gets popped off like a champagne cork, and what was originally an undeniably intense but hollow gore-fest suddenly has some real meat to chew on.

The most obvious interpretation of the film is as a homophobic fantasy about queer women destroying families, and that would be the case, except Marie is the only character we have any identification with throughout the film. We see things through her eyes and we invest in her onscreen presence. So when it reveals that our sole locus of identification is the murderer, although naturally many of us aren’t sure how to feel, many others are forced to concede, murderer or not, we still care more about Marie than Alexia or her family.

As slasher fans, we came to see blood and carnage, and knowing that the intrepid heroine who we’ve been on the edge of our seats with worry over is actually the cause of all the mayhem, it kind of just makes her doubly badass? An impression only intensified by the general awesomeness of Cecile de France. If you’re a queer viewer, her experiences of being marginalised in a traditional family, pining for an unrequited love and feeling vilified for your sexual agency may well all strike a chord and understanding the film in its subversive fullness, it’s such a deliciously incautious and bloody provocation. I especially love Marie’s iconic weapon of choice being an over-sized angle grinder, with the vertical blade contained in a metal “hood” a delicious inversion of Leatherface’s phallic chainsaw. The ending invites you to understand and appreciate everything that preceded it on an entirely different level than you had previously.

There was some controversy around the script for High Tension, which it was claimed had been plagiarised from a novel by Dean Koontz. There may have been some similarities, but Koontz’s novel didn’t have the ending twist, and that may well be why it’s been forgotten while High Tension is regarded as an extreme cinema classic almost two decades later. Even if they did rip off the plot, the thing they added was the part that made it interesting.

Jallikattu (2019)

I think the most impressive thing about this film isn’t that I believed it was a real buffalo, but that towards the end I stopped believing it wasn’t and started to get concerned. The film’s opening declaration is in fact true, and the symbolic animal at the centre of Jallikattu was the work of an extensive VFX department and they deserve all the plaudits going for one of the most convincing pieces of effects work I’ve ever seen.

The film surrounding it is a bizarre one, including moments of dry satirical comedy, incendiary action, and ultimately, a mounting existential horror. Thematically it almost reminded me of Arthur Penn’s 1965 masterpiece The Chase, executed with less intellectual rigor and more ecstatic verve.

The story begins with a buffalo about to be slaughtered by the local butcher breaking loose and running wild through the village centre, prompting the village menfolk to give chase amid gathering unrest. It’s a broad ensemble touching on a few subplots across a myriad of tones, as the village’s richest resident prepares for his daughter’s wedding, and a hunter arrives in town, bringing with him, a grudge against the butcher.

The opening sequence is a strange and vivid musical overture as the village slowly wakes, establishing a muscular and vital tone for the film. There are some exceptional fleeting visual moments as the film goes on, but that vibrant energy does dissipate into as series of rather frayed and hard to follow plot threads that consume the majority of its duration. However, in its last twenty minutes, the film accelerates to extraordinary new heights, as the villagers, both individually and collectively devolve into a bloodthirsty mob, building to the film’s haunting and nightmarish climax. I really have to commend the filmmaker’s ambition and technical execution, even if even at ninety minutes the film’s best ideas feel overstretched.

Color Out of Space (2019)

When reading H. P. Lovecraft’s short story The Color Out of Space, it’s clear that the influence his work has had on horror fiction extends to this work, which seems to have been a strong influence on the likes of Stephen King’s It, with the meteorite and the thing in the well and so on. The story’s terrific, not one of his top tier stories, but I still love it for the chilling and ominous atmosphere and grotesque imagery. I met the prospect of a feature adaptation starring Nicolas Cage, though, with some understandable reservations. Lovecraft’s stories are hard to adapt to screen at the best of times, that’s why the most successful films in their vein just take them as inspiration for an original story, and Nicolas Cage, more than any other actor, raises connotations of the kind of movie it’s going to be. He does have some phenomenal work in his catalogue, when he has a good script and a director who knows how to marshal his alternately wooden and twitchy presence.

For the most part, worst fears were confirmed. Color Out of Space is laughably bad on almost every level and the first eighty or so minutes really is best approached as a horror comedy. The film follows the Gardener family, nominally farmers although they live in a “movie farmhouse” which is to say, a mansion, who find strange occurrences afoot when a meteorite lands in their front yard and seeps into their groundwater. In this and many other elements, the story is skeletally the same as the story, at times even lifting large chunks of monologue directly, and it’s no coincidence that it’s the best writing in the film. However, far from the insular, rather clueless and backwards farm workers of the book, the Gardeners are affluent and characterful. Father Nathan is a jovial alpaca farmer, mother Theresa sells stocks from her attic office while recovering from breast cancer, eldest son Benny is a space fanatic, and daughter Lavinia is into new age religions. These two latter traits seem like they ought to play a big part in such a story, but they really don’t. The dialogue between the family is mostly atrocious, the acting generally poor, especially from Cage, and it’s full of absurd details and inflections that feel like mishandled attempts to give an air of realistic spontaneity to the film but instead just renders everything deeply comical. The other key character is Ward, a hydrological surveyor who narrates the story and witnesses the Gardener’s woes from afar. There’s also a hippie hermit who lives at the end of the property.

Parts of the film in these stages feel reminiscent of the horror of ’80s cinema, such as Night of the Comet, Society, or The Thing, to which there’s a clear visual nod. The closest relative though would be a rather haphazard replication of the previous year’s Annihilation. Some scenes in this section of the film do somewhat work, in that I at least feel like the theme of the horror of the American family and its disintegration are articulated reasonably well. The story had an internal logic, but this works more on emotional logic, when it works at all or is possessed of any kind of logic.

However, once Ward and the local Sheriff arrive, the movie begins to become oddly faithful to the story and spirit of the short story, while successfully managing to up the intensity of the surprisingly epic, psychedelic and atmospheric climax. Many of the scenes in the last twenty minutes or so are recognisable versions of scenes from the book, and moreover, are pretty fantastic. The first four fifths work pretty well as a camp, so bad it’s good, Nicolas Cage movie, while the closing minutes are a terrific homage to the original story with some nightmarishly trippy visual flair, solid writing lifted from the page and even the performances attain a level of gravitas that had escaped them before. The last twenty minutes make for a pretty darned fantastic adaptation that leaves you wondering where this energy was before.

Rogue One (2016)

Perhaps the highest profile film on this list, and the one for which the application of the statement “it’s pretty meh, but the ending was awesome” is the most uncontroversial. Disney’s swing at Star Wars canon was pretty much a complete mess, although I’m a lot more positive on it on the whole. I don’t hate any of these movies, not even Rise of Skywalker, although largely because I was so pleased with The Last Jedi that I was happy to head-canon that as the definitive Star Wars movie and take or leave the others as I found them. The failure of the Disney Star Wars franchise can be attributed to two primary factors: failing to plan out a complete trilogy and oversaturating the market with not only a mainline film every two years (rather than every three as both previous trilogies stuck to), but filling the gaps with spin-offs, rapidly sapping Star Wars of its “event movie” specialness.

Rogue One was the first of these spin-offs, telling the tale of the Rebel spies who secured the plans enabling the destruction of the Death Star, and therefore, that moment that made everyone cheer back in 1977. Following a team of new characters who get just little enough development that we’re not left feeling too short changed when they inevitably don’t make it back from their suicide mission, it’s all pretty stock and routine with the highlight of the movie being a particularly snarky robot. Everyone’s trying their best, but lacking both the whimsical sense of adventure and the family melodrama that defined Star Wars was a near fatal blow in a film that’s aiming for more of a war movie tone than ever before. The facts they succeed and at great personal sacrifice are both foregone conclusions and the film never quite overcomes the sense of detachment that instills.

That is, until the third act when we get a set piece that gives the viewer a sense of “okay, here we are, we know what we’re doing, let’s go!” Our heroes on a mission to go to the place and do the thing, with all the Empire’s and the Rebellion’s best converging on their location to aid or destroy them. The third act has an adrenal sense of pace and intensity that the rest of the film had been missing, and it all builds to one climactic moment that has become synonymous with this film’s shocking increase in quality: Vader.

With the plans for their prized superweapon finally in the hands of the rebels, Darth Vader rolls up his sleeves and takes matters into his own hands. With a crew of rebels throwing themselves at his lightsaber to buy an extra millisecond for the plans to move an inch further from his grasp, Vader goes on a rampage. Fan service it may be, but director Gareth Evans finally gets to remind us he directed The Raid and can deliver an intense action scene. But even that isn’t the peak of Rogue One, not if you saw it at the cinema upon release. A release concurrent with the breaking news of the passing of Carrie Fisher, who reprised her iconic role as Leia to deliver the film’s final, optimistic word and bring a single, bittersweet tear to the eye of fans everywhere. No film was ever handed such an unplanned moment of pathos.

Death Proof (2007)

To conclude with perhaps the best example on this list of a movie truly saved by its ending, Death Proof was the film that inspired this list. However, I don’t need to discuss it in detail as Michael Suarez already explored how this movie is a two-hour slow build to an explosive, cathartic finale that rescues the film from the gross, self-indulgent bore-fest it has been until then. Many still consider it Tarantino’s weakest film, I do (it’s between this and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood), but it’s pretty undeniable that the kick-ass climax is worth seeing.

It’s testament to the power of a good ending that it often means more to get an ending right than any other single part of the movie. The last emotion you give an audience is the one they’ll take home with them. If you can have a perfect five minutes in your film, make sure they’re the last ones the audience sees.