The Sting reminds me of the $24 million-dollar Patek Philippe Supercomplication. Certainly, there have been watches and convoluted crime movies long before, but like that multimillion-dollar clock, this film is the pinnacle of craftsmanship. And it makes me want to do crime.

George Roy Hill directed every aspect into a tale that’s oddly timeless although it can only be told in a specific time period. Winner of seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Director, Writing, Costume Design, Music, and Editing, The Sting stands out not simply because its laden with awards, or features iconic performers, but because it does something a lot of films fail to do. It’s fun to watch.

Spoilers ahead. Those who haven’t seen The Sting would be advised to watch it first. It’d be a shame to lose some of the film’s reveals, and you can only see it for the first time once.

The setup begins in Joliet, Illinois around September 1936. Luther Coleman and his younger cohorts pull a con that inadvertently nets them eleven thousand dollars. At roughly $241,741.50 today, the men think they’ve got a bright future, at least until the origin of the money casts a dark shadow. Seems they unwittingly ripped off a dangerous gangster named Doyle Lonnegan. His swift revenge is brutal. Finding Luther’s bloody body pushes his protégé Johnny Hooker to seek revenge the only way he knows how. Teaming up with a fallen con artist named Henry Gondorff, the two assemble a team of grifters to pull the ultimate swindle.

The plot may sound familiar because by 1973 the heist or caper film was an established genre. Beginning with John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950), these kinds of flicks refined over time through movies like The Lady Killers (1955), The Italian Job (1965), and Le Cercle Rouge (1970). Like any creative expression, the depiction is what sets The Sting apart. Case in point, when people mention a statue of the Biblical figure David, people don’t typically picture Verrochio’s bronze.

Part of what makes The Sting stand out is a stellar script brought to life by an ideal cast. It’s hard to imagine the movie without certain faces. Yet many of the Hollywood icons almost didn’t star in or want their parts.

For instance, according to a making-of documentary, included as part of the Universal 100th anniversary collectors’ series, writer David S. Ward planned to direct The Sting. This made screen legend Robert Redford reluctant to play Johnny Hooker. He felt the film needed a more experienced director to skillfully handle all the moving parts. Fortunately, director George Roy Hill pressed for the job after reading the script, and Ward realized the movie would be in better hands, so quietly stepped aside. Meanwhile, producers initially wanted Peter Boyle for Gondorff until Paul Newman expressed interest in playing the part. It probably didn’t hurt that he, Redford, and Hill had already been successful working together on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

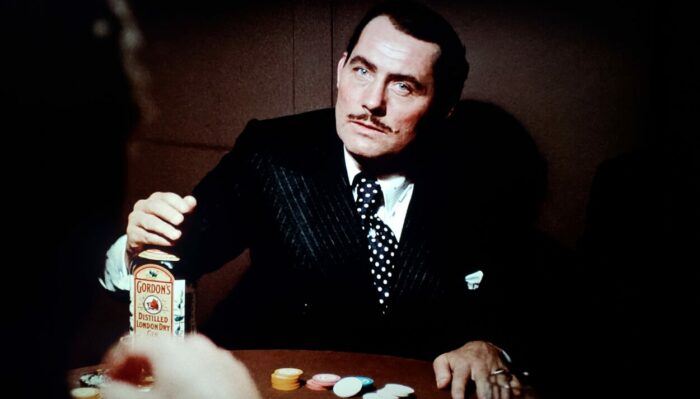

Richard Boone, famous for the western tv series Have Gun — Will Travel, was originally cast as grim gangster Doyle Lonnegan. However, he vanished to Florida without explanation. With the shoot about to begin, and despite some resistance from the director, the role went to Robert Shaw.

![[L to R] Charles Dierkop, Robert Redford, Robert Shaw as Floyd, Johnny Hooker, and Doyle Lonnegan in The Sting (1973). Three men crammed tightly into the back of a 1930s luxury car. Screen capture off the Universal 100th Anniversary Collectors' Series Blu-ray.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Sting-7-700x347.jpg)

That said, the vision of director George Roy Hill cannot be overstated. He saw exactly how to make this intricate picture work. According to “The Films of George Roy Hill” by Andrew Horton, the director conceived the “Saturday Evening Post style to the title cards… imitation of old Warner Brothers gangster films… deliberately avoided using extras…” and how “shots should have the look of Walker Evans’ Depression era photographs.” Hill also collaborated with cinematographer Robert Surtees to compose a maroon and muted brown color tone.

The legendary Edith Head followed this vision into the creation of Oscar winning costumes, while Jaroslav Gebr provided those amazing title cards. The only piece missing was the music. Although Hill knew how he wanted the soundtrack to present, he hadn’t yet settled on a type.

![[L to R] Rober Redford, Harold Gould, Paul Newman, Ray Walston, and John Heffernan as Hooker, Kid Twist, Gondorff, J. J. Singleton, and Eddie Niles in The Sting (1973). Five men dressed in 1930s outfits playing poker, drinking beer, and smoking. Screen capture off of the Universal 100th Anniversary Collectors' Series Blu-ray.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Sting-3-700x393.jpg)

Lara Downes wrote for NPR, “ragtime introduced mainstream America to the simple trick of syncopation in rhythm—that displacement of the beat which causes… a swinging of the hips, a feeling that anything might happen.”

That joyful unpredictability is exactly what the director wanted. Hill pushed Marvin Hamlisch to adapt Joplin’s music, particularly “The Entertainer,” into suitable arrangements. Part of the initial resistance was that ragtime’s heyday was closer to the start of the century. By 1936, it had declined in popularity as the music it inspired took off, most notably jazz, but Hill understood how few people would know it was anachronistic let alone care since this expressive music conveyed the right mood.

Unlike other films, the soundtrack to The Sting is rarely an underscore. It stands out, dominating the scene and seasoning the overall atmosphere, especially several instances where the movie has zero dialogue. Carefree at certain speeds, a slowed tempo made the mirthful music melancholy when necessary. This made it as much a part of the story as any quotable line.

It probably didn’t hurt having producers who didn’t conform to Hollywood conventions. In a conversation with Jog Road Productions, Michael Phillips elaborated on how, disillusioned with Wall Street, he headed to Hollywood with his then wife Julia. They sensed an opportunity given the lack of attention being paid to hungry creatives. As such, they decided to fund film projects major studios ignored. To that end Michael bought two promising scripts from a screenwriter named David S. Ward. The first turned into the film Steelyard Blues (1973) which would flop off the face of the earth, but the other was The Sting.

Ward became fascinated by the confidence men he discovered while doing research for Steelyard Blues. That rabbit hole eventually inspired The Sting. After the movie’s success, writer David W. Maurer sued for $10 million dollars claiming the film ripped off his book “The Big Con”. This nonfiction work does contain individuals similar to or outright mentioned in The Sting such as Charley Gondorff and Limehouse Chappie as well as an explanation of the wire con. Sarah Weinman wrote for Crime Reads that the instructive text provided criminal vernacular and habits for numerous works such as William Lindsey Gresham’s “Nightmare Alley,” which Guillermo del Toro later adapted into a film. And it remains informative to this day.

The parties involved eventually settled out of court. Though Ward continued to deny any plagiarism, his reputation never really recovered. But during production of The Sting, his script was regarded as a glorious gem of original writing.

A lot of that owes to whip smart dialogue. Take for instance the banter between Gondorff and Hooker. The first time they meet it’s clear Hooker is unimpressed, but despite being hungover, Gondorff verbally spares with the young smartass. It reveals them as sharp individuals in every sense of the word.

Another great example is one line by Eileen Brennan. She groggily encourages Gondorff to go to sleep saying, “You’ve done all you can.” The first time through this seems to apply to the big con, but rewatching, aware of certain twists, the meaning changes. And knowing as much it becomes clear why Gondorff is restless given all the porcelain he’s secretly juggling.

![[L to R] Robert Brubaker, Paul Newman, Clarke Gordon, Robert Shaw as Bill Clayton, Henry Gondorff, Mr. Lombard, and Doyle Lonnegan. in The Sting (1973). Newman and Shaw standing around a poker table arguing and being restrained from fighting by the others. Screen capture off the Universal 100th Anniversary Collectors' Series Blu-ray.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Sting-6-700x388.jpg)

Scenes like this keep The Sting sizzling. Then add the fact that there isn’t any wasted screen time. Empty streets or diners make populated spaces seem more alive and important or leave central characters isolated and alone. The color palette suits a gritty mood while staying mirthfully reminiscent of vintage Sunday comics like Alley Oop, Little Joe, or Gasoline Alley. Simple shots of a gloved hand produce a red herring. Every image establishes something moving the story forward. The same is true of dialogue which always gets to the point even when joking around. Body language is equally expressive.

In one scene Eileen Brennan sashays, hips ticking like a metronome through the halls of a brothel. After confidently and coolly dealing with Charles Durning’s crooked Lt. Snyder, she walks the same hall a little stiffer and quicker, hurrying to spread word of the cop’s presence. Dimitra Arliss delivers a lot deadpan, which seems like tired disinterest in Redford’s advances, until a reveal about her character suggests the blank stare of a coldblooded killer. Newman’s eyes are always clocking reactions. And none do a lizard-eyed death glare like Robert Shaw.

There’re interpretative aspects the film never overindulges. The most obvious is Gondorff as a king passing his scepter to Hooker. However, he’s also a person who’s seen through the romanticized myth of being an outlaw. Although there are big cons, more often grifters are working regularly, one con after another, no different than any dead-end office job. They escaped the system for similar confines. Yet, this disillusioned top tier con artist finds a chance to enjoy his profession again.

The Great Depression is the only era this plot could realistically work, but it also provides a metaphorical backdrop for desperation. That unique time period, oddly familiar post-quarantine, when all the systems failed, and people did whatever they needed to survive. Every action made is a bet all in. More than anything else, there’s nowhere to go because the plight is everywhere.

Furthermore, Doyle Lonnegan may be an outlaw, but he’s technically a one percenter. The Gondorff gang is, in essence, ripping off the superrich. This brings up the interesting contrast of criminality, juxtaposing the ruthless killer against the more respectable grifters. Where Lonnegan succeeds through violence and intimidation, they triumph through charm and intellect. Perhaps that’s why it’s easy to see the setup for the big con as production of a stage play.

![[L to R] Eileen Brennan, Robert Redford, and Paul Newman as Billie, Johnny Hooker, and Henry Gondorff in The Sting (1973). Newman and Redford playing cards while Brennan chats with them standing in a doorway. Screen capture off the Universal 100th Anniversary Collectors' Series Blu-ray.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Sting-13-700x332.jpg)

That said, there’re things lacking by contemporary standards. The Sting doesn’t have tremendous diversity, and women barely have speaking roles. Still, the cinematic techniques on display—editing, costume design, music, etc.—can serve as a guide for future filmmakers. Even criticism seeking to negate adulation for The Sting would be beneficial insofar as it illuminates an alternative perspective. Part of movies’ appeal are the conversations they inspire afterward, and this flick can get people talking.

For fifty years, The Sting has been a joy to watch. Infectious music mingles with distinct visuals. Smart dialogue delivered by top tier performers. And it’s never so serious The Sting stops being fun.