The Faculty is an excellent lesson in changing a formula without losing familiarity. Subverting expectations without alienating its audience, this late 90s horror film takes typical genre conventions as guideposts to go in opposite directions. What results is a movie rather cleverly breaking metaphorical patterns.

Genre in general is often a deep well serving up meaning. In fact, some of the best-loved horror films endure because their stories have subtext that resonates with audiences across time. Symbolism can be subtle or overt, but the metaphorical potential of genre is a great backdoor to exploring otherwise taboo topics and uncomfortable societal standards.

For instance, puberty and juvenile delinquency are the subtext of the campy horror classic I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). Though that said, it would hardly be the last fright flick to use lycanthropy as a metaphor. Ginger Snaps (2000) and When Animals Dream (2014) would do even better with similar werewolf themed symbolism while adding a dash of feminism. Then there’s Wolf (1994) starring Jack Nicholson which contains an unsubtle metaphor for midlife crisis.

Vampires have long been a means for multifaceted allegories about sex, xenophobia, addiction, religion, and mortality. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) provided ample fuel to fire criticism of conformity, whether it related to McCarthy era tyranny or communist paranoia. Meanwhile, slasher films can all be seen as cautionary morality tales. After all, as observed in Scream (1996), it’s the so-called “bad” kids who end up dead, specifically anyone who drinks alcohol, does drugs, or has sex. It’s easy with that in mind to then see Jason Vorhees as a symbolic punisher slaughtering those who violate antiquated moral standards.

With such conventions already firmly established by decades of horror films, classics and otherwise, The Faculty was able to build something familiar yet fresh by using the old formula as a guide to what could be subverted. This self-awareness no doubt came from screenwriter Kevin Williamson. Having already done similarly with Scream, he took a story from David Wechter and Bruce Kimmel then composed something akin to several movies. There’re elements of The Thing from Another World (1951), The Thing (1980), the two good Invasion of the Body Snatchers movies as well as flicks like The Puppet Masters (1994) and interestingly enough, The Breakfast Club (1985). However, cleverness lies in the ways in which The Faculty differs from its horror predecessors.

The film is about sinister doings a-transpiring in Ohio. Teens at the local high school begin noticing unsettling behavioral changes in teachers and administrators. Then students start changing too. Soon, a group composed of individuals representing the whole high school pantheon—jocks, goths, cheerleaders, etc.—are running from an invasive, mind-controlling alien menace. Thrust together, they must put aside the petty differences of their cliques and save the world.

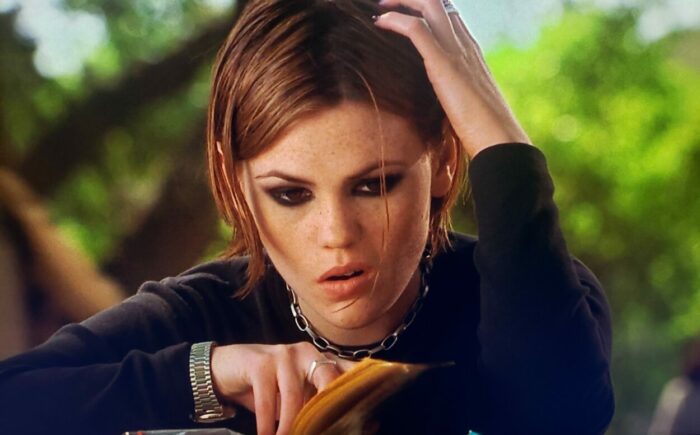

In many ways, it’s a movie about teenage alienation, no pun intended. The heroic characters are largely misfits, such as goth bookworm Stokely Mitchell. Portrayed by Clea DuVall, she spreads the rumor she’s a lesbian to cutoff any possible cat calls in the halls. Then there’s nerd cliché Casey Connor played by Elijah Wood. However, even the popular students feel pigeonholed and unseen. Football player Stan Rosado played by Shawn Hatosy wants to quit the team to focus on academics. Something no one close to him supports simply because he’s a jock.

Historically, misfits aren’t the heroes of horror films. Lorie Strode isn’t a loner outsider. Like Nancy in Nightmare on Elm Street, or Sidney in Scream, she’s solidly middle class with several friends who genuinely get along. Abraham van Helsing and his fellow vampire hunters are also middle class and higher, respected members of society. Even I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) tries to suggest the victims are the popular kids who committed vehicular manslaughter while driving around drunk because god forbid anybody take revenge on such murderers.

Infrequently there are horror films with social outcasts at the center of the story, but those instances tend to be The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) which itself amounts to the slaughter of a van full of slacker potheads. Christine (1983) is a supernatural thriller about a nerd who becomes cool after acquiring a possessed car that kills all his bullies. The overall message being he was better off before the killer car gave him confidence and got rid of his tormentors. The freaks and geeks of films like 976-EVIL (1988), Mirror, Mirror (1990), and Brainscan (1994) court supernatural peril with their lifestyles or attempts to be cool. In other words, such films still follow that formula of the cautionary tale, punishing people sometimes because of their outsider status.

Historically this can stem from a variety of sources. Typically, antiquated notions of morality combine with things like the Hays Code to codify recurrent cinema sins such as the “bury your gays” trope. Something, unfortunately, still seen in modern films like It: Chapter Two (2019) and Halloween Kills (2021).

The point being that despite occasional infrequent outliers, horror prior to the 1990s was primarily about a need to return to the status quo as well as a warning about straying from that state of affairs. Consider The Exorcist (1973) which strongly implies the possession and hellish torment of a little girl is her fault for dabbling in the occult by using a Ouija board. Still, there are a few instances where social outsiders become horror heroes.

![[L to R] Laura Harris, Josh Hartnett, Jordana Brewster, and Clea DuVall as Marybeth, Zeke, and Stokely in the Faculty (1998). Screen capture off Paramount+.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Faculty-10-700x440.jpg)

The Faculty is one of very few horror films to imply there is nothing wrong with being a misfit. In fact, like Fright Night (1985), the things setting our protagonists apart turn out to be their strengths. In Fright Night, a horror obsessed film geek must use his B-movie knowledge to battle a vampire. Similarly, Stokely’s encyclopedic familiarity with sci-fi helps devise a plan of action. (It also helps set up a moment of post-modern genre deconstruction as well as self-awareness.) Casey’s nerdish leanings lead to him finding one of the controlling alien parasites; what anyone else might’ve stomped on sight, he collects out of academic curiosity. The character Zeke, played by Josh Hartnett, is a drug dealer. Yet, in The Faculty, this isn’t a bad thing.

In another genre subversion, only by doing Zeke’s bootleg ecstasy can our heroes deduce who is under hostile alien influence. Plus, his drugs become the only weapon against the extraterrestrial menace. Think about that for a minute. Most other horror films punish teens for doing drugs. The Faculty blatantly states the only people you can trust are the ones on drugs.

![[L to R] Josh Hartnett's hands, Shawn Hatosy, Jordana Brewster, and Clea DuVall as Zeke, Stan Delilah, and Stokely in The Faculty (1998). Screen capture off Paramount+.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Faculty-11-700x520.jpg)

Embracing this distrust of authority figures could be seen as the fulfillment of a trend. In the 1950s, horror films counted on such individuals and institutions to fix problems. Part of the goal of the protagonists in the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers as well as The Thing from Another World is to warn the government so they can take action. Perhaps an even better example is The Blob. In the 1958 version, the United States Air Force is trusted to take the gelatinous monstrosity to the Antarctic where it will likely remain safely frozen. However, in the 1988 remake, the colossal killer jelly is revealed to be the product of a Cold War project experimenting with biological warfare, and when the government arrives to clean up its mess, they fail horribly (albeit entertainingly).

As social attitudes changed over the years, and authority figures became less trusted, so did their fictional counterparts. It’s hard to find U.S. horror in a post-Watergate world with faith in the government. As in The Mist (2007) or The Bay (2012), such institutions are usually responsible for or covering up the horror that occurs. Consider how an increasing awareness of police brutality and corruption may have led to them being represented as less heroic in horror films. Cases in point, the Maniac Cop franchise features a police officer as the slasher, and some of the Candymen in the recent remake are the byproduct of excessive force by cops.

What it comes down to is that The Faculty takes a group of misfit teenagers. However, it doesn’t punish them for being social outcasts. It actually rewards them because what produces that status also allows them to perceive and deal with a danger no one else does. The protagonists then embrace a horror genre taboo by doing drugs in order to stay safe. In the end, their distrust of adults is validated, drug use saves the day, and the misfits become local heroes despite a government attempt at a coverup.

Now, this isn’t to say The Faculty is all subversion. Old fears of female sexuality, unfortunately, get emphasized in weird ways. When the character of Marybeth (Laura Harris) is first introduced, she’s rather coquettish in her flirtations with bad boy Zeke. However, as soon as she reveals herself to be the alien queen, her behavior and dialogue turns to outright seduction. She even sheds her clothes to strut around nude. After morphing into her true form, it’s safe to argue symbolic implications of vagina dentata abound. Then there’s the character of Ms. Burke, played by Famke Janssen, who actively tries to seduce Zeke, her student, after being infected with an alien parasite. In other words, there’s a metaphorical implication sexually forward women are dangerous monsters.

Consequently, The Faculty isn’t a perfect subversion of all troublesome tropes. Furthermore, a lot of this applies primarily to U.S. horror films. Still, it does more than most to alter genre conventions. Yet, the pieces of the old formula all seem to be in play until certain points of the film.

This matters because formulaic conventions are kind of necessary. They operate as shorthand allowing audiences to process what’s happening. At the same time, they set up expectations that can then be subverted, which interestingly enough, allows for a higher degree of vraisemblance because what characters do becomes more plausible since actions fit better with contemporary perspectives. In addition, The Faculty offers the safety of familiarity which audiences find more inviting so willingly encounter new concepts when subversions occur.

People tend to resist changing their points of view. It’s been shown that facts don’t alter perspectives as much as emotions. And the way The Faculty can seem familiar while introducing seemingly taboo ideas—maybe drugs aren’t all bad, social outcasts aren’t slasher fodder, etc.—may make audiences more receptive to inclusive notions in future films. In other words, the formula doesn’t have to be a constraint. It can be a side door to people’s perspective, offering a comfortable setting to experience a new outlook. Even if that setting is a horror show.