By 1994, Tim Burton had already cemented his place as a director of whimsical and gothic spectacle. When we shopped with Pee-Wee at Mario’s Magic Shop in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), we had in essence already shopped through shelves of inspiration for many of Burton’s favorite set props: the recurring swirl of the X-Ray specs, horror and sci-fi Halloween masks, over-sized heads, trick gum, and headlight glasses. The kooky spookiness of truck driver “Large Marge” would become the common place in the realm of the recently deceased in his original follow-up, Beetlejuice (1988). That he followed even that with 1989’s fresh, dark take on Batman, there was no denying that Burton had brought to his directing not only the costumed eccentricities of comic book characters but every impressionable advertisement between its covers, especially those just inside the last few pages—the mail order mysteries and carnival-like promises of sea monkeys, hand buzzers, MONSTER S-I-Z-E Monsters, and magic boomerangs. These were the inked promises of the comic books of the 1950s and ‘60s, much like the decoder ring Ralphie sends off for in The Christmas Story only to be let down by the truth of the secret message, to sell him bland product.

Tim Burton didn’t sell bland products. So, what was it about the carnival and comic book allure for him? One must understand that even in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s being called a geek wasn’t a compliment, far from it, and being a fan of cheap horror films, comic books, and science fiction had all the trapping of being a “geek.” How had it fascinated and suspended Burton as well as so many young audiences all those years, and why had it smacked of the book worm, nerd, and forbidden to so many others? One imagines the Hollywood portrayal of young George McFly in Back to the Future (1985), easily manipulated by his science fiction imagination. Forgive the commas, but we have to consider all of the magic, mutants, X, cathode, and gamma-rayed technologies that began sprouting into hyper-color out of once-black-and-white pulp ‘zines and Hollywood movies in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Each were born of Darwin’s unthinkable science and the terrible might of the atomic age after 1945. The campy, low-budget fears and abominations pumped out in those decades had real and unexplored fear behind them. The stories were also fertile ground for the imagination of those who didn’t “fit in,” has-beens like a particular and mostly forgotten director. Therein is the saturated, subversive world of Edward D. Wood Jr., said director and Tim Burton’s destined and inevitable new subject following Edward Scissorhands and Batman Returns. His story somehow tied all of the elements together and worked as a black and white origin story for Tim Burton’s particular brand of gothic meets wonder.

Up until Ed Wood’s release, Burton was wowing audiences with colorful, gothic fairy tales that were somehow family friendly, no matter how much BDSM leather the protagonist wore. Ed Wood was something different. It was reverent and quirky, charming and still bizarre. Beyond his previous film content and Ed Wood’s penchant for science fiction and horror, this film was mature, adult. As Hoberman states “… Tim Burton, one of the most bankable film-makers who ever lived, expends the credit of his success in sincere, black and white tribute to the obscure, tawdry vision of Edward D. Wood, Jnr (1924-78), the alcoholic, heterosexual transvestite and sometime pornographer known affectionately as “the world’s worst director”.”[1] Tim Burton was taking his modernized Edward Gorey stylings and interests as a devotee to the blended pulp horrors of Universal Monsters and alien invasions—think Mars Attacks!—of science fiction and highlighting an almost-forgotten Hollywood history. It is worth noting David LaRocca’s statement on the usage of these conventions to tell a larger story in his essay “Affect without Illusion: The Films of Edward D. Wood Jr. after Ed Wood.”

Partly the escape to another world serves the symbolic significance of plot and character: many science fiction films (including many disaster films) become ciphers for terrestrial problems such as marriage trouble, political upheaval, fraught race relations, and compromised environmental policy. These otherworldly film fictions seem more satisfying as allegories precisely because we are sure the film is about, well, some other world … With both science fiction and horror, we are then at peace to experience and judge our own allegorized problems at a safe distance.[2]

Still, twenty-five years later, Burton’s Ed Wood is undeniably one of the best love letters to a transition in classic Hollywood. Based on a true story, Bela Lugosi’s journey from popular actor to Hollywood addict and wash-up as told through Burton’s film is as apt a metaphor for forgotten and wasted talent as the plot of Sunset Boulevard, sans the murder. Burton’s telling rejoined Lugosi’s true story to the struggles of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford as audiences’ and Hollywood’s ageism left them clinging to directors who might still notice them—ready for their close ups, ready to be seen at all. See FX’s Feud: Bette and Joan (2017). Ed Wood was Lugosi’s man in that struggle.

Ed Wood is known for cobbling together an unlikely but loyal and recurring cast in wrestler Tor Johnson, personal girlfriends, television psychic Criswell, Bella Lugosi, and Bunny Breckinridge. Tim Burton cashed in on his personal mid-90’s clout to bring his rendition of the story as portrayed by stunning talents Johnny Depp, Sarah Jessica Parker, Patricia Arquette, Martin Landau, Bill Murray, and Vincent D’Onofrio amongst many more. And while it is impossible to deny that Ed Wood’s reputation left something to be desired in the way of quality, Burton was able to translate his appreciation to audiences through his thoughtful casting. LaRocca again reminds us that, “Burton shows that the emotional core of Wood’s films is discernible, evident, palpable even without illusion, without the viewer getting “lost” in the story.” That is to say that even if you saw the cardboard structures shake as actors marched across the set or the strings tied to invading flying saucers, there was heart in the effort.

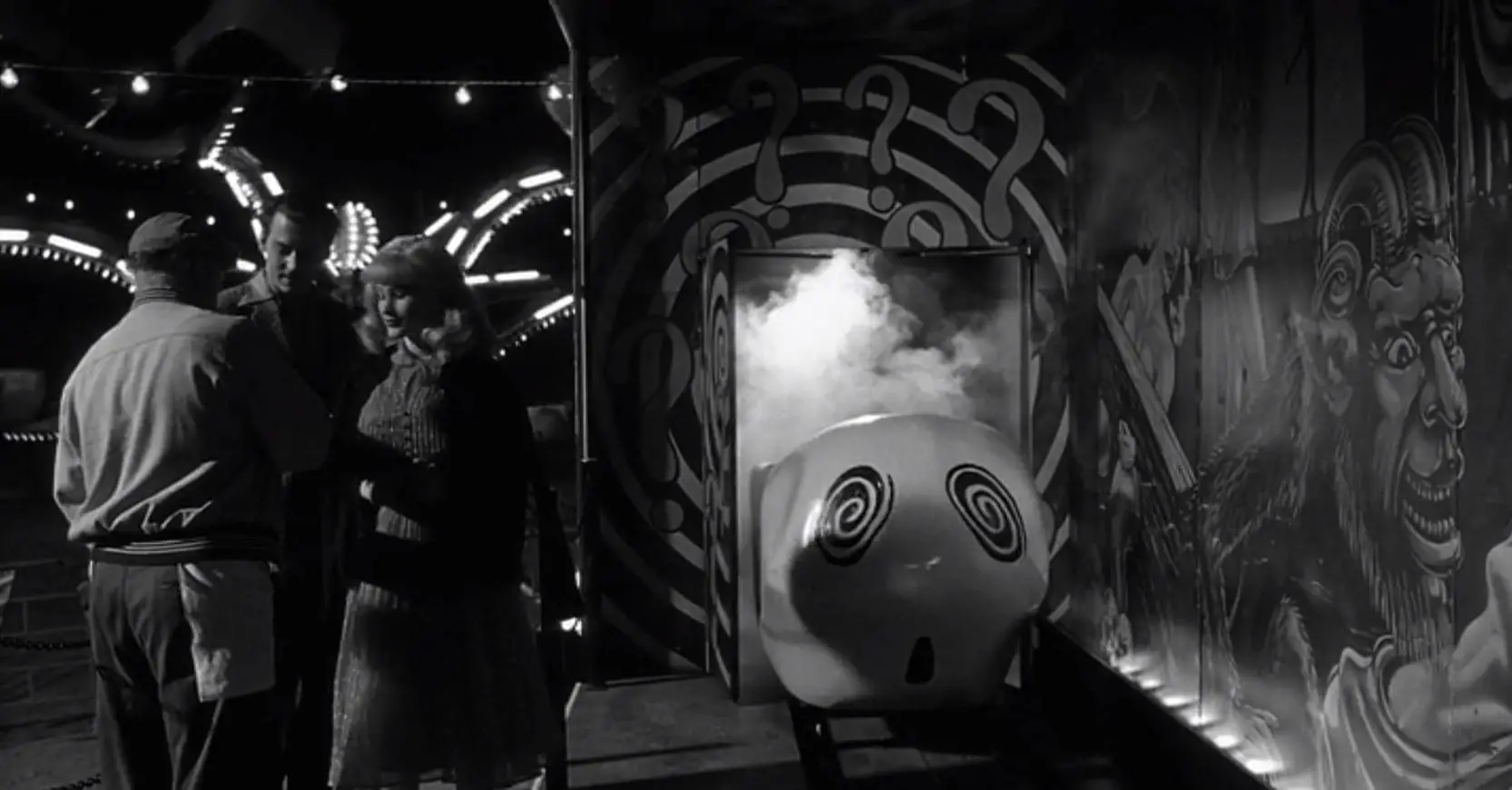

Burton’s film takes Wood’s struggles to make three of his most notorious films as a tryptic view into the life of a forgotten creative: Glen or Glenda, The Bride of the Atom, and Plan 9 from Outer Space. There is not enough room to explore it here, but watching the film today, several Hollywood struggles came to mind. Ed Wood was determined to play his own character, to represent his hidden life as a cross-dresser and all that it meant to him. I’m specifically referring to Glen or Glenda the film and not his usage of the personalities in his pulpy book Killer in Drag (1965). As recently as 2017, we saw the argument that Jeffrey Tambor should have been replaced in his role on Amazon’s Transparent by a trans actress. Further, in 2018, we saw that a blend of horror and science fiction could connect us to the heart in Guillermo Del Toro’s The Shape of Water which defeated all odds in winning an Oscar for Best Picture. The point is that Burton’s Ed Wood tells a story of ambition, humor, and failure that remains relevant. It can make even the most casual of viewer feel like a film student as they see Wood stroll through Hollywood lots and obsess over what he could do with stock footage alone. It’s as if Lugosi and Wood are extending double-jointed fingers to caress you into Burton’s hypnotic eyes, which continue to swirl around and around with X-Ray vision.

[1] Hoberman, J. (1995, 05). Ed Wood … not. Sight and Sound, 5, 10. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/237098905?accountid=7098, p. 10.

[2] LaRocca, “Affect without Illusion.” Book Chapter. The Philosophy of Tim Burton. Edited by Jennifer L. McMahon, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014. Accessed January 28, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, p. 243.