If you were to put five teenagers together in a room today, in January 2020, chances are you wouldn’t hear too much conversation. Their days would be spent checking their Facebook updates and posting to their Instagram feeds before logging into Spotify, earbuds dug firmly into ear-holes, whiling the time away listening to Ariana Grande rather than what the other four teens in the room might have to say.

Sure, I was one of those teens. OK, I never had a smartphone at my disposal, and there was no such thing as Facebook, Twitter or Snapchat, but we still had MTV and Sony Discmans, and internet chat rooms were just beginning to take shape. If we were in a room with a TV/VCR combo or a computer with AOL dial-up internet, there would be little conversation going on.

This was the world in 1995. Ten years earlier, it was much different. There were no TV/VCR combos, computers were pretty much expensive tools for NASA analysts only, and you had to be rich to own a Sony Walkman. There was nothing to do but talk to each other. However, John Hughes understood that even that was not the easiest thing to do. Especially when you’re a teenager and figuring out who you are. I’m not even sure I like who I am. How is anybody else going to like me?

John Hughes wrote The Breakfast Club before he wrote Sixteen Candles and after scoring hits with National Lampoon’s Vacation and Mr. Mom. Hughes felt teenagers were not depicted as true-to-life in movies during this period. Outside of Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Porky’s (a movie I haven’t seen to this day, and I’m good with that), teens were underutilized on film. They were faring better on TV, as Family Ties‘ Alex P. Keaton was charming millions of viewers weekly. Hughes understood not just how sensitive teenagers were, but how wise they were, as well.

The Breakfast Club has a simple story: Five high school students are forced to spend their Saturday in an all-day detention session in the school library of Shermer High School in Chicago. They are there for different reasons: one went shopping during class time, one held someone else down in a locker room, one was found with a gun in their locker, and two are there for unexplained reasons. But here they are—five strangers stuck in a school library with a strict principal to watch over them.

We learn their names right away: Andrew “The Jock” Clark (Emilio Estevez), Claire “The Princess” Standish (Molly Ringwald), John “The Criminal” Bender (Judd Nelson), Brian “The Brain” Johnson (Anthony Michael Hall) and Allison “The Basket-case” Reynolds (Ally Sheedy) who principal Richard “Dick” Vernon (Paul Gleeson) simply refers to as “Missy.” They do not get along, and the tension grows the more Bender dominates all discussion. Early on, he tells Claire that she couldn’t ignore him if she tried, then proves it. The increasing verbal scorn he directs at her angers Andrew as the morning progresses. Bender’s goal is to disrupt everything he can, which explains the reason he’s in there: for pulling the school fire alarm the previous day.

Bender pushes things too far, and Andrew threatens to throw down with him, at which point Bender producers a pocketknife. The threat is made clear, and Bender then imitates what he believes life is like at Brian’s house. As we saw when Brian was being dropped off at school, his life isn’t as rosy as Bender imagines. We see the pain on Brian’s face as he struggles with the decision to correct Bender, but Bender wouldn’t believe it anyway. And as bad as life at home might be for Brian, it’s nothing compared to Bender’s home life.

When people talk about The Breakfast Club they remember the library, the dancing (shout-out to legendary editor Dede Allen, who brilliantly cut this picture), the pot-smoking confessional sequence (more on this), and Vernon. It’s interesting that in the first five minutes of this movie, a lot is shown regarding these characters’ home lives. Andrew gets a lecture from his dad about not blowing his “ride” as a jock, Brian is admonished by his mother (and sister), Allison’s parents drive away without even glancing at her, Bender walks to school himself, and Claire’s situation doesn’t appear to exhibit any kind of parental support. We know when Bender goes off on Brian about his home life that things are not that way at all, but that’s the key to this movie—nobody knows the truth, and everybody is quick to judge each other at first glance.

Even Vernon gets in on the judgment. He sizes Bender up right away and speculates that his life won’t amount to very much at all. We learn later that Vernon has been teaching for 22 years (which means he started in 1962), and it’s likely he’s seen a Bender or two during that time. Of course, you’d think Vernon would have learned how to talk to his students as people during that time, and admonish them. He’s not exactly guidance counselor material.

At one point early in the day, Vernon tells Bender to spend a little more time trying to make something of himself and less time trying to impress people, and it’s not bad advice. It’s possible Vernon recognizes Bender’s intelligence (when he’s not calling Bender a “bum”), but he also realizes Bender isn’t going to listen to him (because he’s destined to be a bum). Bender knows that Vernon’s life isn’t so hot either, so why should Bender aspire to be like Vernon? He’s there with the kids on his Saturday, too. We don’t know if Vernon has a family (if he does, they’re never mentioned), and the only other person he talks to the entire day is Carl the janitor. Bender doesn’t respect Vernon any more than Vernon respects Bender—yet they seem to be the only ones willing to spend their Saturdays with each other. In the end, Bender will eventually leave high school, but Vernon will still be there, six days a week.

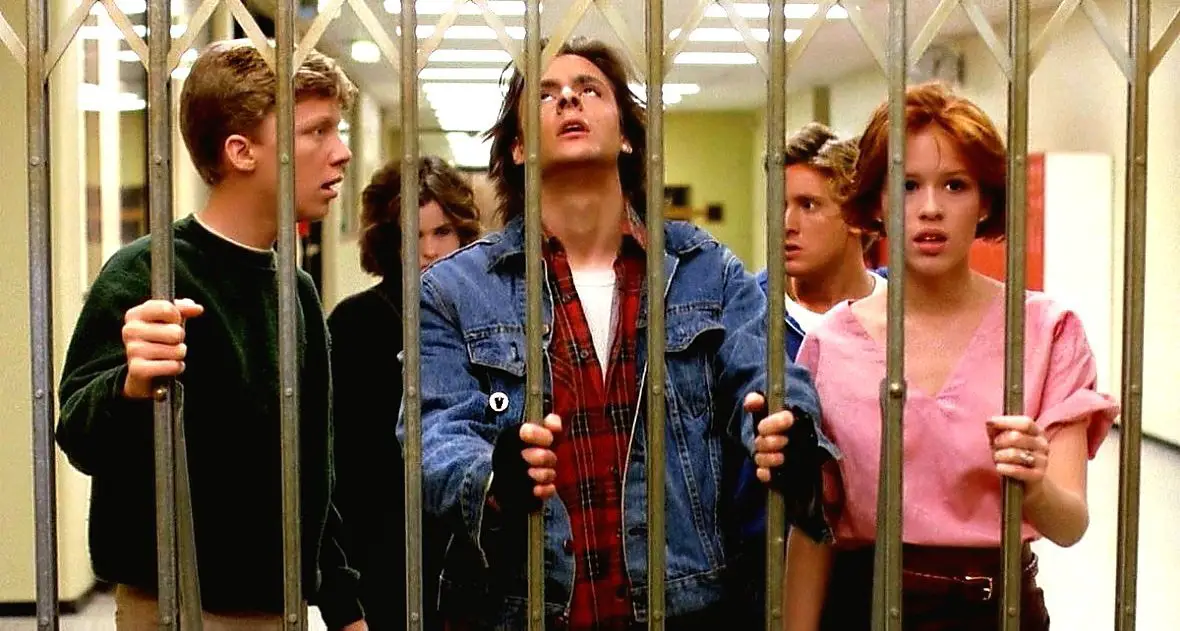

In a way, it’s a prison sentence for Vernon, but Hughes understands that high school is a prison for teenagers even more so, and in one scene, when the gang are running down the hall trying to get back to the library before Vernon catches them missing, Hughes visually illustrates the point.

After The Breakfast Club, Hughes continued examining the themes of teenage class systems in Pretty In Pink and the overlooked Some Kind of Wonderful. After these two movies, he continued examining the differences between white-collar and blue-collar classes with adult actors and characters, first in Planes, Trains and Automobiles and Uncle Buck, and then in two 1991 movies, Dutch and Curly Sue (sadly, his last movie as a director).

These were movies which featured a lovable schlub trying to win the approval of well-to-do, accomplished individuals. It’s a theme Hughes often explored in his movies. When you go back and look at where it originated, you can see in The Breakfast Club how Claire is perceived by Bender right from the start as a chic, fashion-obsessed princess in her Ralph Lauren leather jacket, skirt, and boots. Bender, who is an intelligent guy, probably doesn’t know who Ralph Lauren is or what those items cost, but he knows it’s more money then he’s likely to have handed to him for clothes.

We see this theme in a few other instances. At the start of the day, Claire tells Vernon that she’s sure she’s not supposed to be in “here” (meaning with these people), as if she’s supposed to be in a fancier detention than the one she’s in. Vernon does not respond. It’s unlikely that the school has another library for her to serve her detention in. Claire becomes the focus of Bender’s verbal abuse as the morning goes on, to which she responds with annoyance and revulsion. Bender, sensing this might be his only chance to converse with a girl of Claire’s stature, doesn’t let up.

When Claire confesses that she’s only in detention because she blew off class to go shopping, Bender is not surprised. He’s constantly antagonizing toward Claire for most of the day. He pushes at her until she reaches her breaking point and screams that she hates him. Throughout the day, Bender taunts Claire with names like “Rapunzel” and “Queenie,” as in queen of the school (“School would probably shut down if you didn’t show up,” Bender snarls at her during one heated exchange). He’s the first guy to provoke any kind of strong emotions in her. They’re emotions she can’t deny, and maybe she’s eager to explore them—with him. Their relationship is perhaps the film’s most controversial one for modern viewers (see below).

The library confessional between the five students is the core emotional sequence of the movie. It’s where they confess why they’re all there for the day. Andrew cruelly taped a kid’s butt together, a flare gun was found in Brian’s locker, and Allison admits she had nothing else to do. This might not be her first Saturday sitting in that library, but this one will be her most memorable. At first, Allison just verbalizes her responses in squeaks and yips, her dark hair shielding her face from the cold, harsh world. Allison tells the others she’s used to being ignored in life (though, curiously, Bender tells her early on that he’s seen her before). Allison refers to herself as one of the “weirdos” and says that she has no friends. Even Brian, with his various clubs, has friends. A connection seems to develop between Andrew and Allison throughout the day, but he finds himself especially taken with her after Claire gives her a makeover.

Viewers might ask if this makeover was necessary in a movie in which the central theme is, “Be yourself, because we’re all screwed up,” then betrays that by making over a character who was true to herself—arty, defensive, observant and just yearning to just be “seen.” After her makeover, Andrew stares at Allison in bewilderment. Of course, the argument can be made that Andrew liked her before her transformation. There are instances of this shown throughout the movie as Andrew approaches her to open up after she confesses her desire to run away from her family. Andrew shows concern and care for Allison in these moments. A lot of people may feel that the end can be interpreted as Allison’s need to be “pretty” in order to fully win Andrew’s affection. It’s an argument fans of this movie can debate among themselves for sure, and even Ally Sheedy herself has gone on record as saying it wasn’t her favorite moment in the movie.

The other actress from this movie, Molly Ringwald took a look back at the film not long after the Criterion release. Viewing this movie for her in 2018 meant seeing it now as a parent and as a parent to a teenager who was born in 2003, making her around the same age Claire was in this movie. In an essay that Ringwald penned for The New Yorker, she looks back at some of the more disturbing parts of the movie. Notably, the scene where Bender is hiding from Vernon under the desk where Claire is sitting. Bender’s face is level with her crotch, and Hughes incorporates a shot seen from Bender’s point-of-view of Claire’s underpants (Ringwald adds that “though the audience doesn’t see, it is implied that he touches her inappropriately.”) Even though Ringwald wasn’t the person participating in this shot (a stand-in was used), in the film she’s still a teenager.

Ringwald writes that she understands it was a different time and that compared to other teen movies of the era, this one is unique in that the teens here engage in communication as opposed to titillation. There’s nobody disposable here. Everyone has feelings and a longing to be heard, and it’s no wonder that on those merits, The Breakfast Club is now revered as a significant cultural piece of film artistry. Still, the actress does rightfully point out many less-than-admirable aspects contained in here (and within Hughes’s body of work in general) which do deserve to be looked at in the current environment. How should one respond to them in light of important movements such as #MeToo?

Bender’s treatment of Claire is perhaps the most uncomfortable and cringe-worthy aspect of the story. Bender sees her as a pampered princess who can’t decide if she’s (in his view) having too much sex or not nearly enough. Most of their verbal back-and-forth is only about sex, which often leaves Claire unsure how to respond or react. She has an easier time calling Brian a “pig” when he insinuates to Bender that he and Claire have been together. Bender nags both Claire and Brian about their sex lives but leaves Andrew alone in this area. I now wonder why Hughes didn’t have Bender go there.

Watching this movie today, it’s also problematic the way Andrew’s main insult to Bender is the use of a derogatory term for homosexuality—one which audiences are familiar with, though I’m not going to write it here. We see the word written boldly over Bender’s locker, as well. However, ultimately, it isn’t either of the guys who surprise with talk of sex. During the library confession sequence, Allison admits that she is a nymphomaniac, which stuns everybody. Whether she’s saying that for shock value is not made entirely clear. Allison is the character given the least to say in this movie, but we do know she’s sensitive, artistic and lonely. When she confesses that she’s only there because she had nothing better to do that day, everybody laughs, but not at her. They laugh because they understand her by that point. Andrew grows concerned for her, and I genuinely like the affection he displays towards her. The jock has exposed his vulnerability, which is what she responds to. I’d wager Allison likes the sensitive type, as it’s her character which delivers the most emotionally powerful line of the movie, one which destroys me every time I hear Sheedy deliver it: “When you grow up…your heart dies.”

In the end, it’s up to Brian to write the paper for Vernon on behalf of the five of them, explaining who they are and why they believe they are there that day. In the end, Brian writes that Vernon will only see them as labels and not as young adults, struggling to be seen heard, cared for and understood. Vernon is seen standing alone reading the paper after they have left. We don’t know if he realizes that the teens have learned quite a bit during their day, or even if he cares. We’ve seen them learn quite a lot.

At the beginning of the day, these five were strangers. Nine hours later, they were “The Breakfast Club.” Five people who bared their souls to each other and nobody else. Outside of their parents, these five don’t mention anybody else in the outside world. There’s no mention of boyfriends or girlfriends by any of them. The more popular of the five, Claire and Andrew, have their shopping and wrestling companions, respectively, but how many real friends do they have? It seems unlikely that Claire confesses her uncertainties to her friends, and Andrew is even less likely to open up to his sports buddies. These two really needed to unleash what was going in inside them. This was the day, and these strangers were the people to do it with.

Claire stares into Bender’s eyes for much of the movie. When he looks at her, it’s as if he sees right through her. At first she’s disturbed by this, but eventually she decides to stare back and into him. Revulsion turns to affection during the day, and it’s affection he’s certainly not used to receiving. Bender comes from an abusive home, and when he’s in school, he’s on the receiving end of more abuse from Vernon. His survival instincts are honed, and he even has a sense of humor that, while off-putting, is also endearing. Judd Nelson’s performance as Bender is one of movie history’s most memorable. One minute Bender is tough and threatening, and the next completely vulnerable. How he escaped an Oscar nomination for his work here will forever be beyond my understanding. Truly, he’s that good.

Having just re-watched this movie for this article, I’m struck that within 80 minutes of screen time, Claire goes from abject hate to feeling affection for Bender, despite the cruel taunts and harassment he directed at her throughout most of the day. When she visits him in the closet Vernon placed him in earlier, Claire shows tenderness to him, and for the first time, it appears he really sees her. She’s not the self-consumed “princess” he pegged her as being. For some reason, he got to her heart. They’ve seen each other at their worst yet are still drawn to each other at the end of the day. A bond has been formed for sure, but we never find out how far (if at all) this potential relationship went. Still, It’s a little hard to buy this relationship, especially compared to the more genuine and organic way Allison and Andrew respond to each other.

In the library, when Brian asks what was going to happen once Monday comes around, Claire tells him that truthfully, she doesn’t see a friendship in the cards. Maybe Claire felt differently after that day, and maybe she didn’t. A lot can change between that Saturday afternoon and Monday morning.

What we do know is that Bender will return to the same school and library for another Saturday detention the next week (and the one after that and after that and after that…), so when he does show up the next weekend at 7 a.m., he’ll most likely be with four new people. There will be no Claire, no Brian, no Alison, and no Andrew. Bender will begin his long Saturday with four new strangers. What will be his status? Will he be viewed differently after supposedly spending the week in school at Claire’s side, or will Claire have cast him aside during the week? Will he be back as Bender the thug? We’d love to believe that Claire still values him and perhaps even brings him lunch and keeps him company. But who knows? It is high school, after all.

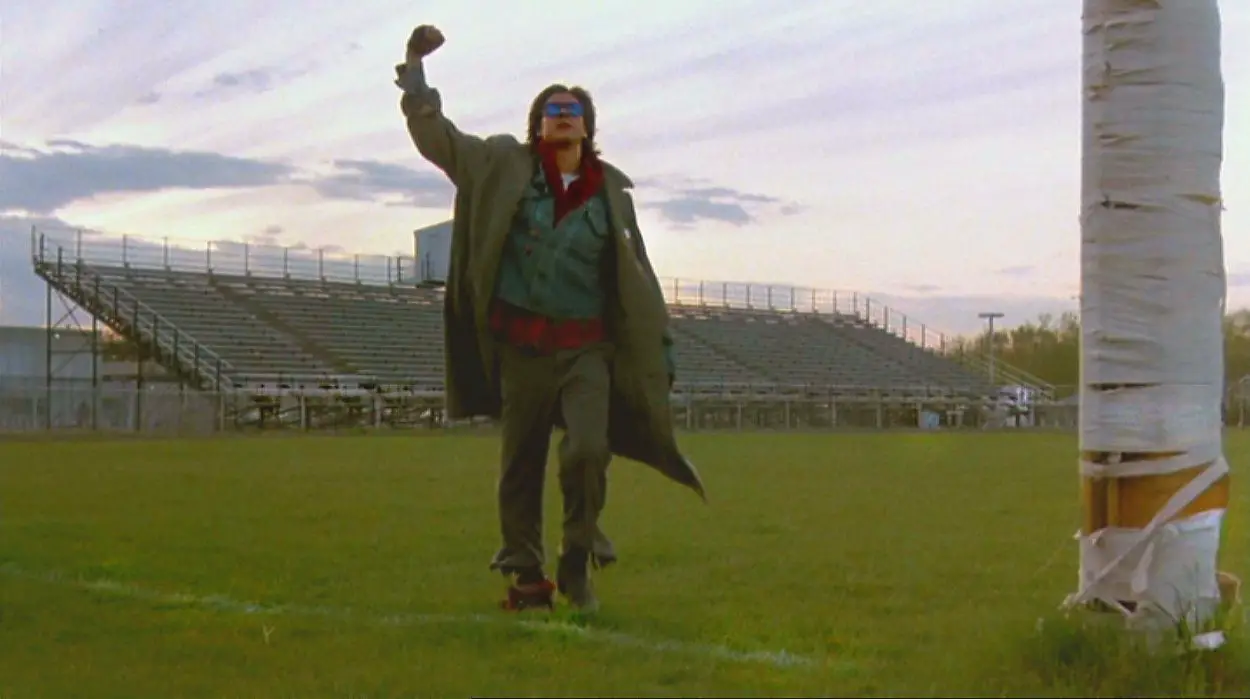

But for one day in March 1984, John Bender along with Andrew Clark, Allison Reynolds, Brian Johnson and Claire Standish were all seen, heard, cared for and understood. And after having made those connections, they leave the school in triumph.