Based in Rochester, NY, the Anomaly Film Festival wrapped up its fifth year this past weekend. Showing everything from When Dragons Collide (1973, dir. Jimmy Shaw) to Robot Dreams (2023, dir. Pablo Berger) and The People’s Joker (2022, dir. Vera Drew), the genre festival had a unique blend of films which made it a must-see event.

Riddle of Fire (2023, dir. Weston Razooli)

Weston Razooli’s Riddle of Fire captures many things on its 16mm film, from the feeling of a summer’s day to a child in rural America, to the distinct unreality of a small town, places where it seems old magic mixes together in a culture with smartphones.

Following a quest to earn the parental control password for the family TV, Riddle keeps its true plot close to its chest as it spirals outwards and back in. The further the plot strays from its original goal, further too does the cast move, leaving their homes to travel across town and even into the mountains to reach their simple end goal.

The world as Razooli presents it is hyperreal, full of places that could exist, but never actually would. A mother’s room where almost everything is a shade of blue, a home filled nearly wall to wall with taxidermy, a forest where mushrooms seem to take hold just too perfectly, this world feels as much like a dream or hazy memory as it does reality. Every sound in the forest is just too loud, as if it were being described by the film’s child cast.

For a main cast of children, at no point do the usual troubles of child actors come across. Razooli and his team seem to intrinsically understand that, sometimes, the best joke is just a child swearing. With the script given, the kids are allowed to actually sound their age, rather than trying to work with sentence structure they wouldn’t use. So much of the film’s plot and memorable lines come from this, from children acting as they actually might. Of course they would stow away in a truck with the person who bought the egg they need, what else would a child do?

The inclusion of real danger into a film like this can so often feel comical, with mustache-twirling villains who fight children. In Riddle of Fire, there’s a certain awareness of this, with the antagonists, a group calling themselves the “Enchanted Blade” who aren’t actively fighting the kids as much as they’re simply annoyed by them, having yet another thing going wrong. It’s only when the two groups are finally placed directly at odds that every single seed planted sprouts, paying off in rapid-fire as they finally have a direct confrontation.

The People’s Joker (2022, dir. Vera Drew)

There are few films that feel so explicitly postmodern as The People’s Joker. For a piece focused on creating anti-comedy, it seems only fitting to call it the anti-movie, even as it’s perhaps the most movie a person could cram into 92 minutes.

Coming from the work of 100 different artists, the film manages to have consistency in the same way that it might, at first glance, seem to lack it. The same themes carry through every shift in style and medium, in the very same way that a trans body is a decidedly non-static thing.

The People’s Joker is about a lot of things. It’s about how you shouldn’t date comedians, for one, being trans in a cis world, the worlds of professional comedy and film, and yet it refuses to water down any of these concepts for its audience. The only options are to accept this film as it is, or to leave. Given how often queer cinema is watered down for a decidedly cisgender, heterosexual, and often-times white audience, the presence of The People’s Joker at a film festival like this is a treat, evidenced by the theater being filled with queer people of all ages and demographics.

Being semi-autobiographical, Drew’s work screams with her voice, taking the experience of years with Adult Swim and using it to bend and shape the DC Universe into something more akin to Tim & Eric.

With a strong script and coherent design choices across its multiple styles and mediums, it’s difficult not to recommend The People’s Joker, if only to experience it. It tells a very trans story but does so in a way unique to Drew.

There’s something so wonderfully messy in Drew’s design that makes it feel so authentic. Rather than play against the film, this mess is seemingly intentional, mixing together so many different parts of reality and metaphor that it really does feel like a head clouded by living for so long on SSRIs and the wrong hormones. As it’s described in the film, it’s all seen through a cloudy purple haze, a mix of so many different things.

The People’s Joker is a beautiful mess. If it were any cleaner, it simply wouldn’t work.

Tiger Stripes (2023, dir. Amanda Nell Eu)

There are many films about menstrual trauma, but none are quite like Tiger Stripes. Threading the needle between a narrative about the horrors of having a body and one of gaining power from it, Tiger Stripes focuses on a community’s reaction to a young girl’s first period and subsequent transformation.

So much of the film seems to be about being viewed as unclean, the change brings with it the need to wear long rubber gloves, and even the other girls talk about Zaffan (Zafreen Zairizal) in terms of her body odor, her difficulty with everything now produced by her body. While Zaffan never seems to be in control, she also never seems to be truly helpless to external forces. The only things that cannot be changed are of the body, the way she herself is changing.

It would be easy to say that the effects work would appear cheap at first glance, but it becomes otherworldly, communicating its themes and intentions with a megaphone. Reality is shown in its own unique way, through the lens of pre-teen girls who fear the changes they will be going through regardless of what they may bring.

In many ways, Tiger Stripes captures much of the horrors of an unwilling puberty in a way that cisgender directors generally are not aware of. There is no consent to these changes, both physical and social, they just begin to happen.

As the film progresses and grows more complicated, so too do its characters and relationships, muddying the waters. Just as things grow more complicated as people get older, it’s reflected in the social complexities of this all-girls school. The changes seen in Zaffan are shown to change everyone around her, in some cases literally as well, as the public perception of who and what she is begins to shift. The same girls who happily danced and played with her only days before suddenly begin to shy away from and mock her for changes entirely outside of her control.

More so than so many other other films shown over Anomaly’s festival, Tiger Stripes feels lived in. It’s world, all of its characters, it all seems real in a way, as if these people live these lives every day. Even as things are changed irrevocably, they stay grounded in this place. The homes really do look like places people live, and the school has just the right amount of dirt to it to make it feel as if people really do these things every day. These may seem minor, and perhaps they ought to be, but it shows that films that dedicate themselves to their world and locations really do benefit from it.

Sleep (2023, dir. Jason Yu)

Possession or paranoia? Jason Yu’s Sleep asks this question over and over as a couple is faced with the impossible task of navigating life with a terrifying sleepwalking disorder. Hyun-Su (Lee Sun-kyun) spends his nights with a growing tendency to act like a man truly possessed, putting his acting career, wife, and newborn son at risk.

Yu leaves ambiguity everywhere in Sleep. Not only is there a seemingly plausible story of possession at play, but there’s a simultaneous medical dilemma. By centering this story in two separate worlds, it’s able to dance around giving clear explanations in a way that masterfully serves the story, obscuring any singular cause for these strange events.

Through a combination of folklore and medicine, Sleep covers a lot of ground in its 1 hour 35 minute runtime. So much of this film seems to have come together in the edit, with scenes seeming to speed up more and more as Hyun-Su and Soo-jin’s (Jung Yu-mi) lives begin to spiral rapidly out of control.

With a strong focus on props over visual effects, Sleep shows that less can be so much more in horror. There’s no need for overworked artists to create a monster in this script, or show any kind of transformation, and the film is so much stronger without it. There’s a banality to this evil, even if Hyun-Su really is possessed, he doesn’t jump at the first opportunity to hurt anyone. Everything escalates slowly as new methods to stop it prove unsuccessful and grow more and more desperate.

With a strong marriage as its central focus, Sleep manages to avoid too many questions. Any obvious solution, such as having Hyun-Su sleep in the car or another apartment, is shown to be incompatible with the story being told. Every time an easy solution presents itself, Soo-jin’s focus on overcoming these problems together comes back, with a dedication to their marriage proving to be the only way she can continue to work through it.

So few horror movies find the time to really flesh out the relationships between their characters as the film goes on. While it may seem at first that Sleep is going to follow this trend, it comes as a breath of fresh air when it becomes apparent that the changes in their relationship are central to the plot.

Stopmotion (2023, dir. Robert Morgan)

Perhaps the strongest praise I could give Stopmotion is that I was already texting friends about it as I was leaving the theater. If nothing else, it’s a film with incredibly provocative imagery, constantly pushing its plot to the next logical extreme. If Sleep was all about a slow descent into madness, then Stopmotion is a freefall.

Following a stop-motion animator trying to find her voice in a new project, Morgan shows what happens to an artist who loses all reservations in the pursuit of her art. While one of the largest twists may seem almost immediately obvious, at no point is it trying to be a surprise. There’s a certain unspoken respect for the film’s audience in this, the film never pretends to be smarter than the people watching it.

In spite, or perhaps because, of how the film portrays stop-motion animators, there’s a clear love for the craft here. The film shows how painstaking the process can be, with adjustments in the millimeters being repeated over and over for mere seconds of footage. Just as how the script moves gradually in its escalation, adjustments over time lead up to an almost inevitable conclusion.

One of the best parts of this film is the odd moments of realism within it. In both the sound design and its script, it shows how squishy a person can be. Stitches being ripped back open aren’t seen as something casual, but an excruciating process. Likewise, it shows how a single fall can incapacitate a person, and how landing the wrong way can change everything. The ways that it shows flesh tearing and blood oozing out really do look and feel natural. The reactions to these scenes were visceral, with audible gasps and noises from the audience I was in. Personally, Stopmotion is a film that made me feel my every nail and hair, an awareness I would rather not have.

Far from existing solely for shock value, Morgan uses this imagery as escalation. From the very start, it becomes clear what the end will have to be here. Trading an eye to see one’s own death is no easy decision, and losing your vision to be consumed by what you end up creating is nothing to be taken lightly. Standard puppets are slowly replaced by worse and worse alternatives, the same work that consumes the mind consuming whatever flesh is available. Again, these movements are gradual, shifts in millimeters that work toward an end.

Stopmotion may be one of the best films that I have no intention of watching for a very long time.

Robot Dreams (2023, dir. Pablo Berger)

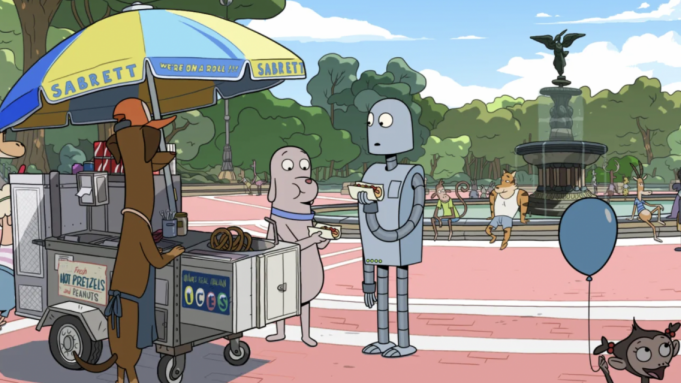

Berger’s Robot Dreams might unintentionally be one of the best breakup movies ever made. Following the classic tale of a dog and his robot, Berger injects tragedy as the robot becomes trapped, with the dog unable to try to save him. Following both the dog’s changing life and the robot’s dreams of being reunited, Robot Dreams really seems to be focused on the process of moving on, and the difficulties within that.

Even without dialogue, the characters in Robot Dreams are all well-defined. The way every individual moves around is unique, from the loose, meandering walk of the carefree Robot to the tighter, more risk-averse steps of Dog by his side. Even beyond how different animals behave, there’s so much character on this screen, everywhere you look. To a degree, even New York City plays a character, with so much of this film clearly being a love letter to the city it was in the ’80s and ’90s.

Even at its bleakest, there’s so much joy in Robot Dreams. The little movements, the expressions, and the soundtrack, always serve as a reminder that things are never quite so bad. Even as what’s happening on screen is ripping your heart out, nothing is beyond repair.

There’s something beautiful in how Robot Dreams portrays loneliness. The reality of it, desaturating the color out of life, removing someone’s drive to exist beyond basic needs, it all feels so painfully real. As soon as things change, the world itself lights up. Frozen dinners become real food, time spent wallowing turns into activities—it all feels very, very real.

Far from another animated feature just about the importance of friendship, Robot Dreams really seems to be focused on what happens when two people are forced to separate. By circumstance or otherwise, the film tells the story of what it’s like to move on and find your place in the world again. With so much of the film showing examples of catastrophic thinking, it’s refreshing to see examples of what it can be like, with how it starts to consume a person’s thoughts over and over. The titular dreams aren’t all happy, and as more time with unanswered questions goes on, the darker things get.

By the end of things, what’s important isn’t that Dog and Robot reunite, but rather that they both can move on and be happy. It’s a struggle at first, it always is, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying.