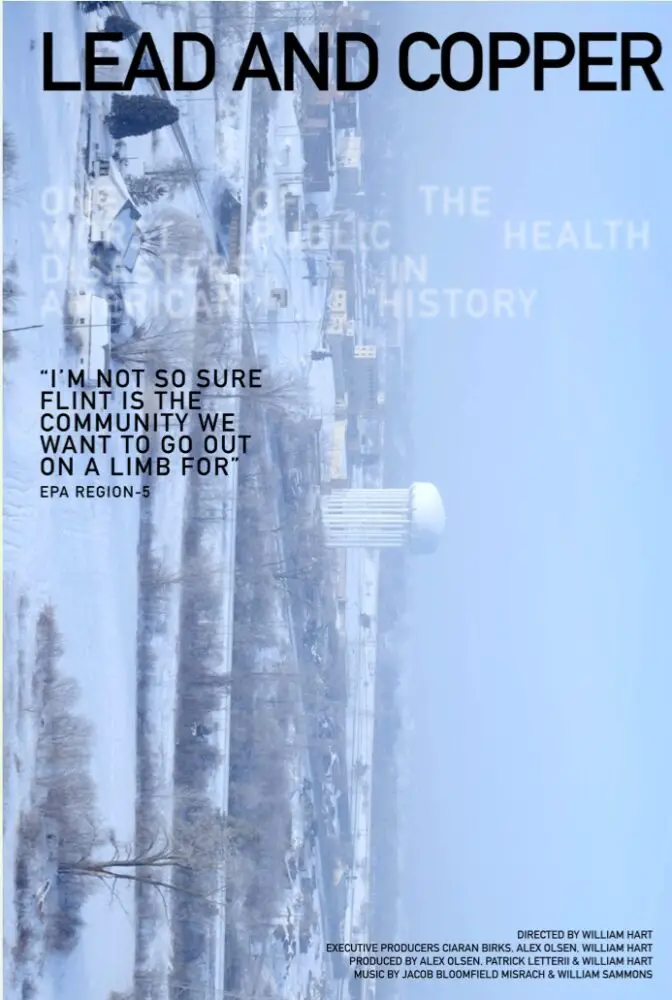

Director Will Hart was on the ground in Flint, Michigan, in 2016, covering the evolving water crisis there for Yahoo News. It was there that he saw first-hand the events that led to thousands of people, especially children, being poisoned by the city tap water’s unsafe amounts of lead. Those events—as well as the failure of the state to act until citizens rose up in protest, and the failed attempt to cover up the matter—are the subject of his new and first full-length feature documentary, Lead and Copper.

Lead and Copper details the events of the Flint water crisis with an up-close and personal perspective, based on interviews with those who were there, confronting the unsafe drinking water and the officials who stonewalled them. The crisis may be, technically, passed, but the environmental racism and social injustice Flint’s citizens faced make Lead and Copper a warning and a call to action to hold governments accountable for their negligence and arrogance.

Director Will Hart has worked on award-winning documentaries like Half-Time (following Jennifer Lopez’s journey to the Super Bowl halftime show) and Copyright Infringement (about Australian artist CJ Hendry). He has also followed and photographed The Doobie Brothers during their 50th Anniversary Tour and directed music videos for artists such as Pile, Rachika Nayar, Maneka, Bambara, Shop Talk and more. His previous shorts have been shown at deadCenter, Nashville Film Festival, Athens International, Hollyshorts, and more.

Hart spoke with Film Obsessive Publisher J Paul Johnson about his experience directing Lead and Copper and the fallout from the Flint Water Crisis. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Film Obsessive: Hello Will, where are you and what are you working on at the moment?

Will Hart: Right now, I am in Brooklyn, New York, but I’m working on shooting and behind the scenes of a horror movie, and I can’t say which one, but it’s going to be probably coming out sometime next year. It’s very different than what I usually work on.

That’s exciting. I hope you navigate the snow and the weather there. Lead and Copper, a film that I recently reviewed, is just out now. It explores the Flint water crisis of about a decade ago. I’m just going to ask you to take us back in time to how you came to the topic and what your experience was there.

So in 2016, about eight years ago, almost to the week, I was sent to Flint for Yahoo News. I used to be a freelance video journalist, and I was there for a week and a half, two weeks. And I was covering the Flint water crisis. There was so much information on a plethora of issues that were going on that were related to the Flint water crisis and aided why their water was contaminated. And that really motivated me and enraged me really, to want to do a bigger piece and to want to do more stories. With a little bit of luck and some help from my friends Alex (Olsen, co-producer) and Pat (Letterii, co-producer), we got very low funds together and started this feature, basically going back and interviewing the same people that I interviewed for this Yahoo piece. That’s how the movie started. We went back to Flint from New York a dozen times or so. I lived in Detroit for a little bit to do a lot of principal photography and that’s how the movie got made. It was really a labor of love.

And it sounds like no small amount of anger there, as well as what was happening in Flint. So some of your principal subjects and interviewees like Janay Young and LeeAnne Walters, those are folks that you knew from the first moments really there on the ground in Flint back in 2016, or did you come to them a little later?

I met Lee Anne a little bit later in. I first met her husband actually at a Virginia Tech water sampling distribution center in 2016. Right on our first trip. And then it wasn’t until probably a year later that we interviewed Lee. But Janay Young, Leon El Alamin, and Tim Matin, we met almost in my first trip. It was either my first or my second day there. I knew a few people from hanging around after shooting these Yahoo pieces at a bar near my hotel. And the bartenders and my friends I made there were like, oh, you should go to my friend Janay or oh, you should go talk to LeeAnne. And that’s how we met. It was just showing up and being like, hey, what’s going on? Can you sit down? And their presence in the film morphed from there.

It feels really important from a viewer’s perspective to be able to latch onto those firsthand stories of how individuals were impacted. I also imagine that there were others involved in the crisis who had very little interest in speaking to a documentary filmmaker about their role. Did you also try to speak with like the emergency manager, the governor of Michigan at that time, other state and local officials? What were those efforts were like?

Yeah, I have two anecdotes. We obviously tried to speak with the emergency manager, and we tried to speak with Howard Croft, the Public Works director. We got close to maybe getting Howard Croft. I think at one point it almost happened. Emergency managers never responded to our reaching out. Former Governor Rick Snyder never responded. I did have an interview with former Gov. Snyder’s treasurer, but his interview was very in the weeds. And while it would have been revelatory in some ways or another, it would have been very difficult to explain how we got there or why we were interviewing him.

Then we tried to interview a lot of congressional members who you could see towards the end of the film when they did the Oversight Committee. And we got a lot of Democrats, obviously. Elijah Cummings was fantastic. Brenda Lawrence, Eleanor Holmes, Dan Kildee. But Jason Chaffetz and all the Republicans did not want to be interviewed. I walked into Jason Chaffetz’s office in Congress and he quickly asked me to leave. Yeah, it was interesting navigating who wanted to be interviewed.

There were also former EPA officials that we interviewed who were there during the writing of the Lead and Copper rule. They were not happy to be involved and came in expecting to dismiss all the claims that lead was that big of an issue in water quality or in water across the country. And I wish I could have integrated those interviews into the documentary, but it would have to explain a lot more in the documentary, and it would have been very, very long.

I recognize that’s always an important part in documentary filmmaking is keeping the length of it manageable, especially when there are so many diverse materials. And also keeping it focused. I suppose you could always Errol Morris one of your interviewees, and undercut them with a little bit of quirky music or a little bit of a late cut or something like that.

But I did that! There was a cut like that. Yeah, there was an edit like that at one point. I don’t think it’ll see the light of day.

Fair enough. You mentioned that the one interview was “in the weeds.” Can you just explain what you meant there?

There is a lot of policy and bureaucracy that goes behind switching a municipality’s water supply from one source to the other. What happened with the switch over to the Flint River? It was a catalyst of creating the contamination and the lead poisoning. And there was a document that—this is conjecture, but possibly circulated that would approve that they didn’t want to spend money on treating the water at the water plant. But after we did that interview and we couldn’t find the exact document and we basically didn’t have the paper, we basically didn’t have enough of the evidence. We didn’t want to include it in the film.

It’s still in the end, I think, such a clear account of the events in Flint. I wish I had been able to share your film with my college students back when I was teaching Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha’s book (What the Eyes Don’t See) on the matter. Could talk a little bit too, about some of the challenges of working with such a diverse set of materials for a documentary? You’ve got your own interviews, you’ve got pieces of legislation, you’ve got a lot of archival footage. You’ve got what I imagine must be a pretty dense thicket of bureaucracy to navigate. What are some of the challenges in trying to put that together and really make it a very coherent and causal narrative?

That was the hardest part. You know, we could have made this movie in a way where someone was just narrating everything, but it was very important to me that we showed the exact evidence of what was pointing to. It was pointing one domino, setting up the other in the line, knocking it down. I have to give a shout out to Ryan Felton at The Guardian who requested a release from MDEQ and Michigan and EPA that had a plethora of emails and data and analysis. As well as Virginia Tech, which released their own information and their own datasets and their own emails that they had collected. And former EPA official Miguel del Toral, who released information to ACLU with LeeAnne Walters. So there was much to go through. And then that pointed to how the crisis got made and how it was attempted to be swept under the rug.

But then on top of that, we need to really explain to an audience what things like corrosion control was and how bad lead poisoning is and why are there lead pipes in general? We think of lead pipes, we think of lead now as a very toxic material. But when it was being utilized, communities being built, and even back in the Roman times, we didn’t know that, right? There was a lot of scientific and water chemistry research that I had to personally do because I’m a filmmaker, I know I did very bad in chemistry in high school. So it was a lot of education. I’ve read a lot of books, read a lot of papers, talked to a lot of people. And it also came out of doing interviews as scientists across the country and learning from them and being like, okay cool. I can explain what you explained to me in a different way, but now I need to simplify that for an audience and edit that into the movie. So it was a big task and I think we did an okay job.

I think you did an excellent job with it. I’m wondering, are there models or influences or other documentary films or filmmakers that really inspire you or that you look to when you’re thinking about your own work.

Yeah, it might sound weird, but there’s this documentary by Werner Herzog called Lessons of Darkness. It’s about the Kuwait war in the invasion of Kuwait. I think it’s hard to tell what it’s actually about because it’s just like aerial footage of the aftermath of this huge invasion in the Middle East that we did. I was transfixed by that movie when I first saw it and I started Lead and Copper and I really like the idea of having this scope of everything in movies. In Herzog’s movies, I feel like you see everything on the screen and it’s told to you in a way that is very matter of fact. I know it’s a little bit rehearsed, but I wanted to incorporate that. Then people like Alex Gibney, who are so well researched and go beyond documentary filmmaking into investigative journalism that he’s a huge role model to me. Because I wish I could just be that detective and follow one injustice for months and months and months at a time and discover as much as possible. I think those two, Herzog and Gibney, are my big guys. But then Harlan County, USA, was another great documentary that I was following when we were building the edit. I looked back at that movie for how do we show the people who are bringing the Flint water crisis to the light as heroes and as people who are in charge of their own destiny. I looked at Harlan County for how to do that, because that’s an incredible documentary about West Virginia and the coal miners there.

Those are all great examples and it makes me want to ask, when did you see them? Are those films that inspired you to become a documentary filmmaker? Or was documentary filmmaking something that was always in the cards for you? And then as you’re developing, you’re looking to others to kind of hone your own instincts and abilities.

I don’t really know if I’ve always wanted to do documentaries. I like doing them. I did some when I was in high school that were okay, when I was just starting out in college too. I think that my emotional reaction to the Flint water crisis after going there, was really what pushed me and motivated me and Alex and Pat to want to make a documentary out of this. Had Yahoo sent me to another place to cover another injustice, something else could have motivated me even more. But, you know, I have other documentary ideas I would love to do. I’m still researching them right now, but I think when I was growing up and when I started becoming a filmmaker, I don’t know if I always wanted to become a documentarian. Because it is daunting.

And it’s honestly a little scary to tell someone else’s story, and I don’t even like saying those words, it’s just daunting to be like, okay, this is about real people and I really hope they like it. Thankfully, I think everyone who’s in the movie, who has seen the movie, Lead and Copper, has really enjoyed it. But it wasn’t until I showed it to them and it was done that those fears started to go away. That was very important to me, that everyone in Flint who has seen it, and everyone in Newark who has seen it, liked it, and Dr. Marc Edwards liked it. If they didn’t like it, if there was an issue with it, I would have thought the film was a failure. Everyone’s accolades, everyone’s reviews, and what people are saying about the movie now, I’m very happy about. My biggest goal was to make sure that everyone who was in it was like okay, yeah, this is exactly what happened. Thank you for making this or, you know, you didn’t get anything wrong. That was a big fear of mine.

That’s really fascinating to hear. I see a lot and review a lot of documentaries and one of the first things I’ll acknowledge is it’s easier to make a bad documentary than it is a good one. As I’m sure, you know, they can go wrong in a lot of different directions. I’m wondering, since most of the events that are covered in the film place, we now nearly ten years ago, what you are thinking about making that film at this particular historical moment, post Covid. If you feel like the Flint water crisis is something that is, should we say, resolved for lack of a better word, and what, if anything, we have learned from it?

So the official word from people at Virginia Tech and from the state of Michigan is that like 95% of Flint’s pipes have been replaced. Now, I don’t really think that that matters. I think that because the citizens of Flint had been lied to for two years. I don’t think that they can ever trust their water again and rightfully so. I don’t know if I was poisoned to, if my water was poisoned, and I kept on saying, to my city officials and to my state officials, something’s wrong, and they kept on saying no, no, no, it’s it’s okay—and then they finally admitted that it was poisoning kids—if I would ever drink the water again. So I think that the issue is beyond scientific or technical technicalities. It’s all about like gaining the trust back.

When we interviewed Mayor Ras Baraka and Kareem Adeem from Newark, that was in the middle of Covid and they were wearing masks. There was a part of me that was hesitant to wait until possibly the pandemic subsided a little bit and maybe they would go on camera without their masks. But I think that Covid and the pandemic in general has shown how there are cracks in our infrastructure, beyond the literal infrastructure and cracks in our health care system and what is important to our government in some ways. If the state government of Michigan really cared about Flint at the time that the water issues were getting bad and people were experiencing health problems, then they would have looked into it more.

I think we saw a similar reaction to how our government reacted to coronavirus and how some people reacted to coronavirus. So that’s why I included it in the documentary. If I could tie Covid to Lead and Copper at all, it’s eerily similar in some of the reactions and some of the ways that state officials and federal officials downplayed how serious a problem was. At the end of the day, it’s like if you’re just trying to keep people safe and healthy, you know, why don’t we put a little bit more effort into keeping people safe and healthy, especially our children. I don’t understand the mental gymnastics that go behind that and that counterintuitive thinking.

You have communities who are experiencing lead poisoning, people of color, and communities of color, mostly low income. The lead poisoning is already on top of all these other issues that they’re experiencing day to day. They don’t have access to good grocery stores, they don’t have good public transit. My goal for the movie, and I don’t know if I was completely successful with it, is to show that water is just one thing that we need to exist. Once that’s contaminated, it shows that there are other problems going on.

Well put. I was going to ask what ideally you hoped documentary can do. What can good documentary filmmaking accomplish? That’s clearly part of it. Is there more you’d like to add there?

Yeah, I think it’s important for documentaries to tell how people can combat the oppression that they’re facing. I also think it’s extremely important—and I wish more documentaries that were popular today did this—to inform the audience, to give them a little bit of a history or a science lesson why this is happening. Because if you then understand the history and the science behind a specific issue, then it’s easier for you to comprehend other issues. Beyond that, you can be like, oh, okay, well, General Motors left Flint so there wasn’t as much money coming into the community. So that’s why you have those dominoes, as I said earlier, that are set up that make the audience understand as opposed to them walking away with more questions or walk away from them just really upset or really scared about what exists in their own country. I love a lot of documentaries, but I’m afraid that some are just here to scare us and just here to make us sad, as opposed to give us the information that we need to put everything into context.

Thanks, Will, where and when can people see Lead and Copper?

We’re figuring that out. There’s a few festivals that we are going to announce, but we’re still talking to a bunch of different distributors. But if you reach out to us on our website, we can tell you directly what the local film festival you’ll be able to see it at or what local screen you’ll be able to see it.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us at Film Obsessive. I hope Lead and Copper gains the widest audience possible. I wish you every bit of luck with your future filmmaking.

Thank you very much. This is an excellent interview and I [appreciate] your wonderful review.

![[L to R] Conor McGregor and Jake Gyllenhaal as Knox and Dalton in Road House (2024). Amazon MGM Studios. Bearded Knox attempting to stare down the zen like Dalton in a dive bar as the two get ready to fight.](https://filmobsessive.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/road-house-RDHS_2024_UT_221006_RADLAU_10908_R_rgb-200x133.jpg)