Film Obsessive first met United Arab Emirates filmmaker Nayla Al Khaja three years ago, when she was first making the transition from commercial filmmaking to features. (You can check out Jason Sheppard’s interview with Al Khaja here.) Since then, she has directed and executive-produced, from her own concept, episodes of The Alexandria Killings and her short films Animal and The Shadow, which led to her writing and directing her first feature film titled Three, based on an exorcism she witnessed first hand, and which is just recently completed.

As the first female filmmaker from the U.A.E., Al Khaja is conscious of her responsibilities in the industry, eager to represent herself and others like her with her cinematic storytelling. Three connects Al Khaja’s personal experiences and cultural background with narrative themes of loneliness and family dynamics as its characters navigate the conflicts of cross-cultural beliefs.

Al Khaja spoke with Film Obsessive publisher J Paul Johnson as she and her team look forward to Three‘s theatrical release. Scroll below the video for a transcript of their conversation, slightly edited for clarity.

Film Obsessive: Nayla, your new film Three is just one of your many accomplishments. Can you tell us where you’re speaking to us from and what you’re currently working on?

Nayla Al Khaja: I’m so glad to be with you here again after three years. “Three” keeps following me everywhere. I am actually in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It’s been such a journey because I shot this film in the midst of in the middle of Covid.

It’s just recently completed. Now, after that time that you’ve invested in it, can I have you tell our audience, in your own words, what Three is about?

So in three words it’s Exorcism in Islam. And in more words, it’s about a mother and how far she’ll go to save her son against different adversities in the context of Arabian challenges because she’s divorced. So it’s a taboo topic. And then she has to raise this boy who’s very difficult and coming of age. He’s 13 years old and he has to combat his inner voices. So it is a film about [demonic] possession, but the treatment of it, I would say, is very, very different than many of the exorcist films that keep coming in the market. And I tried to stay away from clichés and I tried to be as realistic in my filming as much as possible.

It was about three years ago that you spoke to our Jason Sheppard and at that time, I think you were really just in the very seeds of planning this film Three. What was it that drove you to make this film?

I lived the story. It’s based on a true story that happened in my family. Where I was in front of the person who was not well for almost a year and a half. And I saw how distraught the mother was. It almost broke the family apart. There were a lot of mullahs, as we call them, which is equivalent to priests who come and exorcise the kid. And I sat there watching this child scream in agony. And there were just some horrific incidents that I just can’t get rid of out of my system. And I feel like making these films, weirdly, it’s also therapy at the same time because it was a very, very difficult period and, you know, we almost lost him. So as much as it’s horror, it’s also a psychological drama- slash-kind of like the horror of losing your child.

It sounds like just an incredible experience. And I mean, I’ll confess I’m someone whose only knowledge of exorcism comes from having watched films, from Hollywood-ized treatments of this. I’m interested to hear anything more you might have to say about what the actual experience might be like. And then we can talk a little bit about translating that into cinema.

Yeah, so the actual ritual that takes place in the Islamic world is very different than like, let’s say Christianity or Judaism or any other religion. Because when I did my research, there were 25 cases (of exorcisms) that I was following. Besides the case that I lived through, the most severe way of exercising a person is using the method of using cotton, or what we call cottoning, which is really unheard of and probably never captured on film.

I mean, maybe someone has, but I’ve never seen it myself. And it’s where they stuff the nose and ears and mouth of a person to a point where they can’t breathe. Because they feel that by doing so it suffocates the devils in you and they find a way out, you know, and they just don’t stay in your body. So it’s just a school, an ideology, Not every mullah believes in this. It’s the extreme method. But I wanted to capture that to showcase that there are kids that go through this extreme method.

I don’t think it happens anymore. The story is an old story. It was in the late ’90s, so I haven’t heard of cases that go through that extreme method. But since it has happened, and it probably happens in rural areas now, in different areas, in different countries, in our vicinity, in the region. I mean, then I won’t be surprised if the cottoning process still happens.

It is something that we see on screen in Three. And I’m just wondering what you’re striving to do cinematically to try to present not only technically the logistics of an exorcism, but also the feelings of horror and terror that are there for those who are involved.

The mother (Maryam, played by Faten Ahmed) who’s this modern character, lives in Dubai, runs her own bakery, she doesn’t believe in (exorcism) obviously. She knows her child has a mental issue. But she lives with her sister and family that are conservative. She has that battle and then she has the battle of the British doctor, Jefferson Hall, who is in Oppenheimer and Hours of the Dragon. He was my Dr. Mark Holly who gets involved in the story.

And I like that because in the real story we had, albeit he was German, we had a doctor from the West who gets to see the story. He’s not saving anyone. He’s there to get lost with the characters because he builds this affinity with Maryam and her son. They feel very comfortable with him. He’s very compassionate and he too feels the same kind of connection with this family. He’s not very verbal, it’s all like body language but you can see that there’s that connection. They almost make a beautiful family. If it weren’t for those like restrictions and limitations, you could just see that Maryam would end up being with Dr. Holly and he would take her son under his wings.

But unfortunately, it’s not the case. It reminds me of The Remains of the Day. I think there was a bit of inspiration coming from there. Obviously, that part is embellished, that was not really in real life. The mother barely had time to scratch her head. And I also wanted to say that there are some themes that are very original. They have never been filmed in this context, where the kid’s left toe is fused with the adjacent toe. And that’s where possession metaphorically and physically took place. Because in our culture, anything left is sinister. Having something happening to your left body part is a sign of unwashed sin.

I just like the fact that she’s the mother, she’s carrying the sin of not being pious, of not praying, of not doing these things that are expected of her, you know. And then she’s in a forest of people who are trying to impose these ideologies and she’s fighting it off. But in the middle of the movie, she kind of loses hope and takes the religious route because nothing works medically for the kid. As I said, like the treatment is more on the drama side than the kind of jump scares and levitation. We don’t have any of that in the film. And that’s why it probably feels very real that people do connect with my characters because it really does feel like a problem that can exist. But the solution they used to solve to help this child was very extreme.

I will credit you in particular for the character of Maryam. And also the actress (Faten Ahmed) who plays her does an excellent job. She seems like a woman who is really caught between different belief systems and also really driven by nothing more than her love for her child and her desire to see him well and whole again. I’m wondering if there are filmmakers who have influenced you or whose work you wanted to diverge from in the making of Three.

Perhaps a lot of like Arab filmmakers from North Africa. I love their work. You know, the Moroccans do really well. Also, Iranian cinema inspires me. I would say. I’m just trying to think of names from the West. Nothing comes to mind. I mean, there are like these big commercial directors that I really do appreciate. But I’m inspired by Iranian cinema a lot.

I wanted also to give some credit to the actor who plays the possessed boy, Ahmed. His name is Saud Alzarooni, and just looking at the press materials. He’s 16 today. I’m assuming he would have been what, 14 or so, 13 perhaps during filming, is that correct?

Yeah, that’s correct. And he actually told me later that he gave me a white lie because the poster said 12, maximum 13. So he’s like, I was actually 14 plus going on 15. When he told me he was I was 13, he lied. But it’s amazing because he’s never been on film before, he’s never acted, not even in a short. He has some experience with theater, but he’s never really done a movie before.

I’m wondering what you have to take into account with his youth when making the film. How much of the narrative he is exposed to, what his limitations are or strengths are as an actor that he can bring to the role, perhaps especially during the exorcism scenes.

He’s so good at switching emotions you feel like he has mild schizophrenia. He does this at liberty to make me laugh, but he’s so good with his timing. It’s incredible and it’s just something that comes so naturally to him. He’s very smart, bright, you know, it was someone who takes instruction and then he gives me more than what I expect, like he always tries to push himself. But one thing I noticed, he was extremely depressed in some of the scenes because he has, in real life, a very broken relationship with his father. He hasn’t seen his dad for a long time. And then this is a complete coincidence and the kid in the film is the same, the character Ahmed. So he almost becomes Ahmed after a while when we’re filming. And that’s quite sad, but he does embody it really well. And you feel like it is coming from a very, very authentic place with Saud the actor.

It does feel like that and his role strikes me also as very well written in terms of his adolescence. That his outbursts take place at moments of humiliation or shame or arousal, those feelings in adolescence, those urges that are difficult to control—and in this case, apparently impossible.

I had a really, really hard scene written and we weren’t allowed to film it because we shot in Bangkok. There was a scene in the bathtub that we had to completely rewrite that because I couldn’t film what I had originally written, which was based on a true story. So I couldn’t do that. I’m a little bit gutted, but I understand. Because they’re children and you know, there’s a lot of like red tape around kids. I get it. But I really wanted to capture the fear the girl went through in real life. It was kind of grotesque. He had his tongue all over her ear and reading verses. It was pretty disturbing but obviously we couldn’t do that. You know, I had to find a solution where I’m close to it, where I’m kind of alluding to or insinuating that feeling, but without actually physically doing it. Some people think it worked better that there was that tense anxiety that people felt.

But yeah, there were a few scenes where we had to sacrifice because of censorship.

I understand too. And I don’t know personally that I would need to see exactly what happened. I mean, I know from the film that something bad is about to happen and that something bad did happen. I don’t know that I would need to see exactly what did happen there. But I also understand as a filmmaker, you want to be able to shoot and produce that which you’ve written.

Yeah. And one thing I wanted to say, and if filmmakers who are watching this, if you have made a film and you have a young boy—ADR (Automated Dialog Replacement), that bit me really hard because when I met Saud after in post, his voice had completely transformed. And I said, “Sorry. Do you actually sound like the devil for real now? Like it’s so thick and squared, it’s like, where’s that little innocent boy? It’s gone!” So I couldn’t ADR him and I had to make the best of what we had.

I’m also curious what else goes into the exorcism scenes. Like I saw, for instance, a credited contortionist?

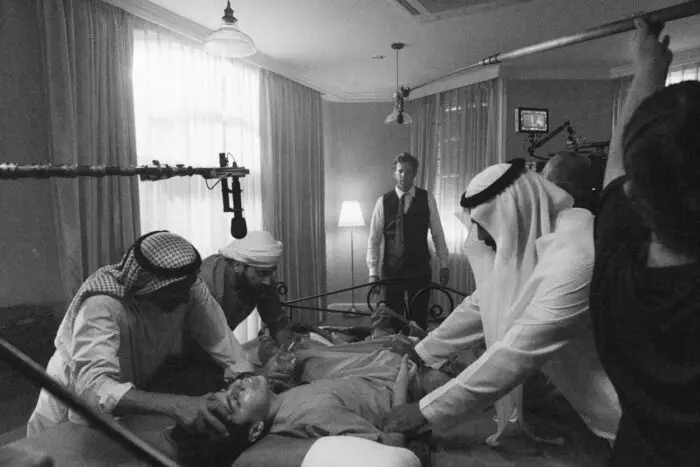

Yes, of course. It’s grueling to scream constantly and be a bull and wrestle and all that stuff and you have men holding you down. And so basically we had to have two body doubles, so we had a kid his age who took over when Ahmed was tired. And then we had the contortionist who did some of these crazy hand moves. So as you can see, we didn’t go too crazy with the supernatural because I wanted the script to feel more real than not. And I know that the ending is, to me, very metaphoric, but it can also mean that perhaps the curse perhaps never left this family, but the little moments or the few moments I used with VFX, I think they’re effective because when they do happen, you appreciate them. And it’s not like, you know, flying saucers and plates flying everywhere. I try to avoid doing that.

It also strikes me, Nayla, that Three is a film that works very much like a maternal melodrama, right? Where a young mother, very often a single mother, is really working to resolve a conflict in the best interest of her son and is pulled in different direction by those tensions. So this is a film that’s clearly grounded in psychological horror, but also works on some other principles that are more based on the relationships between the characters as well.

Correct. And you can also see that the themes of jealousy and what we call in our culture, I don’t know if any of the North American countries or sorry states have it, which is what we call the evil eye, like someone jinks, basically. Here it’s very deep rooted and I know like in some areas around the world, like let’s say for instance in Italy and Sicily, they really believe in like the evil eye. And that’s why like they don’t publish stories of their children online just in case they get the evil eye.

So you can see the sister, Noora, embodies those kind of schools of thought and how startlingly different she is from Maryam. And I thought Noura (Alabed) did a great job. I always say like Noura is the spice on our baryani, because she brought that spice to the film where, with her dry humor she was the reason behind everything, because obviously she’s not as successful or let’s say as pretty or she didn’t have kids. So, she had she longed for, wanted to be Maryam, but she couldn’t.

I wanted to ask you as a female director in the Arab film industry if there are others who have influenced you or mentored you along the way. And also how you see your own vision as a filmmaker as you forge a new path for yourself in this industry.

So when it comes to mentorship, I am the first female film director in my country. So there wasn’t really like, you know, a pool of people that I could just, you know, ask to support and hold my hand in the journey but I give credit always where it’s due. Like Ismaël Ferroukhi, a wonderful director. There has been some good solid names in our industry. Men who really were almost like father figures in the sense that they really took care of me in that way and helped me along the way to watch international independent cinema, expose me to that in the film world. And that had impacted me.

Actually, my father would probably be the first person I should credit, because this is all by complete sheer coincidence. He didn’t know he was doing this, but he was actually collecting films and he had the biggest film collection anyone could imagine. You know, I mean, starting from BetaMax and VHS. And growing up, I think I watched the Exorcist when I was eight, which of course, I shouldn’t have done that, but there was this brown cupboard and I’m still short, by the way, so I would like go on a stool and have this magic key. And this key would open this closet of, you know, another world of movies. And I would sneak them because I wasn’t allowed to watch. And I would take a film each day and my nanny would make sure that no one watches and we’d watch the film together. I’d even tie my sleeping blanket around my neck to save like two or three seconds. If he comes, we have everything, like we take out the VHS, lock the cupboard. I’d run to my room and the blanket would come on top of me right away. Because I was obsessed with his collection.

So I’m sure that’s where the, as they call it, love fever started, at a very young age. And yes, and now I see it passing on. I have when people ask me, like for you, what does success mean to you? And for me, it’s the impact. You know, when I see young adults sending me e-mails and now mostly on Instagram. How they would love to intern with me, how I’ve been, you know, impacting them. I speak a lot at university, to them I’m their role model, so it’s very endearing. It’s really beautiful because it comes from a very, very, very deep place in them. And they need that. They need more examples like myself so that they can be able to get and tell stories.

It’s easier now to tell stories than any time before because of streamers in the Arab world. And because there are like now more women obviously doing it—and men as well. But I think that this is a wonderful time to inspire a younger generation. And obviously I have to help myself to help them. So the idea is after Three, something magical happened to me. I got signed up by Zero Gravity Management with Sarah Arnott, who’s now my manager. And she’s now bringing international projects to my attention, which wouldn’t have happened, if, obviously I didn’t finish my first feature film.

Congratulations for that! And honestly thank you so much for sharing that anecdote, your superhero origin story, If you will. I’m really honored and privileged just to have heard that. It’s really truly affecting and your passion and your talent for your filmmaking really does come through. I’m looking forward to audiences internationally being able to see more of your work in the future. Where and when can people see Three?

At the moment, I have Vox Distribution distributing all around MENA region and we are speaking to some parts of Asia and North America. We still don’t have theatrical over there. But I believe that once I have a good case study, if it does well in one of these countries, it will have a rollout in Asia. And that will automatically help me roll out in different territories. Fingers crossed!

But if anyone wants to see or have a flavor of my work, I do have two films on Netflix, albeit not feature films, they’re shorts. The Shadow, which was the proof of concept for this film, Three, is actually on Netflix and it’s streaming in over 130 countries, and so is (another short film) Animal.

Nayla, are you working on another horror film in the future or are you diverging out into different genres?

Yes indeed. I’m actually filming end of this year and the funding is in place. Everything is ready to go probably next month. We’re going to be rolling. The reason why it’s end of the year, it’s because of the weather. Otherwise we would have been able to shoot it in the summer. It is a beautiful gothic, dark, psychological horror, but more on the fantasy side. And it’s about the five stages of death narrated through the left ear of a woman who has the disease. And it’s every stage of death is manifested through a creature in the mountain. It’s really stunning visually, it’s a very surreal film.

And I have to say this. I was very, very fortunate that two-time Oscar winner AR Rahman read the script and gave me his manager. That was quick as 24 hours he signed on a script because it really inspired him. And he’s going to do his first Arabic song. He’s done over 160 films, like Slumdog Millionaire, a lot of Danny Boyle’s movies, he’s composing the main song. And it’s a very strange wedding song because it’s a human marrying a creature. So it’s an unholy union. So that’s going to be very interesting to see once it’s done.

I’m looking forward to that! I just wanted to thank you so much for taking the time to visit us at Film Obsessive today. Nayla, I wish you the very best of success with Three and with all of your future projects. I just want to say also, it’s so important for the film industry in every country to be able to tell stories from diverse perspectives, from diverse authors, directors, and origins. And your filmmaking is something that seems very deeply committed to that. We just wish you the very best with all your work.

Thank you so much and I want to thank Film Obsessive. More than ever, now is the time for people to connect. And I hope that film, if anything, brings us closer together because it’s a language that everyone understands. I really do appreciate your time and having me on your show, and I hope more people watch different cinemas. Because I think if anything, it does bring peace.

To learn more about filmmaker Nayla Al Khaja and her past, present, and future projects, visit https://naylaalkhaja.com/.