Minnesota filmmaker Louise Woehrle’s new documentary A Binding Truth recently won an Audience Award at the Twin Cities Film Festival, where the film played to enthusiastic applause. The film tells the story of two men—one white, one black—who share a last name, Kirkpatrick, and learn of their shared history nearly 50 years after they first met in high school.

De Kirkpatrick and Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick’s lives and careers may have taken them on divergent life paths, but much later in life they begin to learn of, and continue to explore, their shared past in a story that speaks to America’s longstanding racial divide and continuously difficult reconciliation with its past.

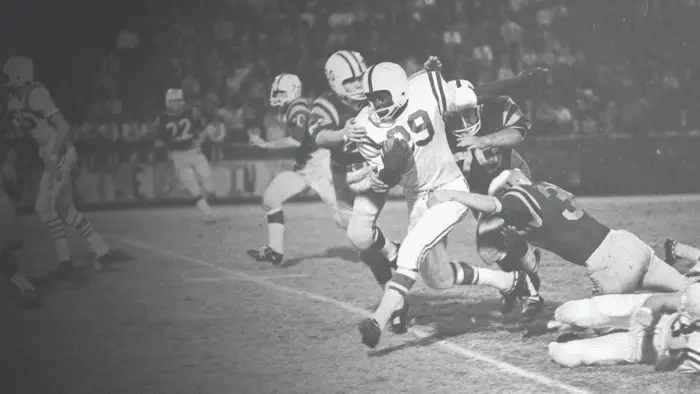

De Kirkpatrick was a senior at Myers High School in Charlotte, North Carolina when a new student, Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick, transferred there in 1965, the formerly school newly open to integration. De went to Harvard and a long career as a forensic psychologist. Jimmie played at Purdue on a football scholarship before a knee injury ended his career. Forty-seven years later, their lives crossed once again, which is where A Binding Truth begins its inquiry into their shared past.

Just after A Binding Truth‘s Minnesota premiere, Woehrle spoke to Film Obsessive’s executive editor J Paul Johnson about the film’s reception, distribution, and production. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Film Obsessive: Louise, congratulations. For our readers who’ve yet to see the film, how would you describe it to them?

Louise Woehrle: This story is about “a binding truth”—the title of my film—a 90-minute documentary feature about about two men who reconnect 47 years after high school. They didn’t know each other, but they knew of each other, when the black man integrated into the white school he was a superstar athlete. A lot happens during that period of time in his transfer and then there’s a whole story about that that sets the stage for when they meet so many years later.

It’s an amazing film. What’s it like to come back to your hometown and to show it to an enthusiastic crowd like TCFF’s?

You know, it was so warm and wonderful. It’s the best. So many people have heard about this film for a while now and have been so eager to see it. I had missed the deadline because we had a longer version of the film for the Charlotte crowd. All the money for the film was raised in Charlotte, and so I felt this urgency to show them. We had a really nice cut at one hour and 50 minutes, but I knew that it in order for us to market it and distribute it, we had to get it down to 90 minutes, and so we did that.

And it was just so great because people have been waiting here patiently. They showed up at 10 am in the theater and even got popcorn. I was worried that it was going to be 10 am and would anybody come. The reason it was 10 am, getting back to the other story, is I had missed the deadline because for the Twin Cities Film Festival I had the hour 50 version that I had to cut down to 90 minutes.

So I was screening the film to test the DCP which is a digital cinema projection file and and so I was testing it at the Showplace Icon theater with Codey Livingood, and he said to me “Louise, you need to go talk to to Jatin [Setia] over at Twin Cities Film Festival. This film is so good. You need to go over there.”

He had tears his eyes and I just thought you know, he’s right what the heck, the worst Jatin’s going to say is no. So I went over there and Jatin said “How long is it? Do you have a trailer? What’s it about?” And he knew me from my previous film [Stalag Luft III] as well. That afternoon he got back to me and said “We made a slot for you.”

And so that’s how it happened. Being in front of my hometown was great because there are people who are close to me know the story, but others who I know through just being in the community don’t know really anything about it. So it was fun to see their surprise and their appreciation and their open-heartedness and I think what I felt the most in this situation was just so much love, just so much love.

This film does that to people: it opens their hearts.

It really does! Everyone around me was totally enraptured in the film and eager to hear what you had to say about it at the end. So you’ve shown a longer cut of A Binding Truth in Charlotte and a slightly abridged cut here in Minneapolis. Has it shown elsewhere?

It’s shown a few other places so far. One was the Footcandle Film Festival in Hickory, North Carolina. Another was the Heartland International Film Festival. They’re so well-respected and it’s very competitive to even get into that festival. When Greg Sorvig, the Artistic Director from Heartland, reached out in an email, it wasn’t a form letter. He just said, “You know, I love your film!”

That was very nice, I’ll confess!

As a documentary filmmaker, you’ve made a lot of choices about what to include and what to leave out, and this seems like a difficult story in that regard. The reach of the subject is so tentacular in that the two men’s lives are intertwined in ways that they could never have anticipated and that are difficult to trace.

I think the most challenging part was how to tell the story that had already happened to incorporate it in a compelling way and have it be a moment where maybe people are a little surprised. To recapture that that was probably the most difficult thing to do in terms of their individual stories.

I already knew that De was working on a book. De is a forensic psychologist; he is very much a analytical person and very pragmatic. Jimmie, I knew, was a softie, emotional, a feeler, and if you were to meet De, you wouldn’t think he was a feeler, but that’s the beauty of the story. As we continue down the road of their journey, it was really cool to see the onion peel back on De.

Jimmie didn’t need any peeling back. He just kept showing up, you know, because he’d been at genealogical study for over 20 years by the time he met De. But I think for De, his sensitivity is revealed at moments. That I wasn’t expecting, and it’s it just was perfect. If you were going to make this a narrative movie and have a script and all that, these characters would work well against each other because they are different and yet they find this common ground in this friendship despite their very different personalities.

I just kind of fell in love with both of them for different reasons and I think once they knew that there was integrity behind the story in terms of telling the truth, which they did, they just got more and more free.

I appreciate the note that they almost characterized each other by opposition. What do you feel like you learned most about each of them in the process of making the film that maybe you didn’t realize coming into it, knowing just the factual outline of their relationship?

I think what I realized was that De lost his brother, who he was very close to and nine years older. And Jimmie represented for De this opportunity to be connect with another man that wasn’t his brother but he felt brotherly love towards. I loved seeing his joy come around.

Any man in that stage of his life could just to look away from the experience and dismiss it as an episode long ago in the past. A lot of people might make that choice. So I think it’s to De’s credit that he doesn’t. I wanted to ask just about your particular perspective as a “Northerner,” so to speak, headed down to the South to make this film. Did you have any ambivalence about that?

I didn’t see it as a “gig,” I saw it as I’m going to be dedicating this much time to something that I’m going to be totally wrapped up in. So I want people to feel respected, especially Jimmie and De, and that their story is safe and I’m not going to exploit them and I’ve got to run things by them. I’m going to show them a rough cut. They get to weigh in. I was willing to do all that because it wouldn’t serve the film if I didn’t do it that way. I’m not a big network. I’m just an independent filmmaker who wants to shed a little light on truth and get people thinking.

I was paying close attention to the sound design. The use of an aural soundscape to recreate the past was especially well done. As was all of the animation of the still photographs, the old archival footage, the documents dating back hundreds of years. How long this has been in process?

The post-production went on for a year and a half. So we didn’t start doing the motion graphics, the fun stuff, until we had really a rough cut. But in that process I was able to imagine—like I’d wake up at three in the morning and say to myself, oh that prose that De wrote about white bones about the slave cemetery, I want to use that.

I love having lyrical pieces in my films where it lets the audience interpret how they want to take this in and it’s a break from talking heads. And so, I knew how I could use it in that cemetery. And it just so happened the day we were shooting that it was really cold and windy and blustery. It was perfect. I had a a piece of paper with the excerpt typed out and I said, “Can you just read this?”

We were outside and he read it in one take. And that’s what we used, that one little take. These ideas would come to me that worked out, and it’s almost like you get a nudge from somewhere. The other nudge I got was the plantation that appeared because of my sound guy: he discovered this property called Holly Bend and I went over there and I was blown away.

So we had to get the park and recreation rights to shoot there, and we did. It worked out great because of a scene that we had shot with the historian and Jimmie and De saying well, Jimmie could have walked across the (Ross) plantation on his way to school.

I wasn’t prepared for De looking out for Jimmie like he did. Keep in mind that De is analytical, he studies people, so even with me, there might be a moment where he felt a little protective of Jimmie, and that was really sweet. De is a guy who grew up in the South with a racist father, surrounded by racist relatives and friends. How did he not grow up to be a racist too? But I saw his heart and the depth of his heart represented by his voracious appetite for all those books he read on slavery and his dedication to write his book, Marse. I realized he was driven by his curiosity and seeking the truth of his family’s slave history and slavery in America.

It just told me so much about what drives him, and I’ve great respect for that, you know. He was on his own journey to figure this stuff out. He also wants to share what he has learned with the world. It was cool to see this revealed in real time.

Did you have any trepidation about experimenting with technique?

I didn’t know I was going to do the animation at that time because I didn’t think it was possible. I thought I was just going to use imagery. My guy (VFX Supervisor) Ben Watne at SPLICE, who I’ve worked with on other projects, said “We really are wanting to get more into the the 3D animations for projects like this. So if you’d let me, I would love to try.” And so he does!

If I wrestled with anything, it was the responsibility to not screw it up. I always say this but it’s so true. I feel like I have a sonar dish on me and I’m just listening, I’m just taking it in, and then you’ve got to kind of let it kind of go through your heart and your whole being in the storytelling, and then ask “How does this serve? What’s what’s this going to give us?”

Well, I figured that out pretty quick, but the 3D animation took it to the next level. They pulled it off and it was just amazing. That and the augmented reality sequence as well with the school where they step in. Dr. [Willie] Griffin from the Levine Museum told me about their app—it’s called KnowCLT for “Know Charlotte”—and it will take you through the old area that was destroyed. You go to these little footprints and you pull it up on your app and then you hold up your phone and you are back in the past. So I thought, if we could show that, it would be cool. And we had them walk into the scene where the old school is there there.

Because we had that time to really think this through choreography-wise and in camera angles and depth and all that, we didn’t have to reshoot anything we got at all. So that was amazing because I had such talented shooters.

It worked out really well on screen to bring the past alive, which seems like part of your task as the director here.

Yes, it is, and we have the technology now to be able to do that and we have talented people, But it isn’t just executing it technically. [In one scene we show] former enslaved people out there working in the field. I said it’s got to be right. It can’t be too close. It’s just got to be right. It’s pretty great when you have a great team.

You mentioned at the screening today too that you had a son that contributed to the project and that Jimmie has a son who contributed to the project as well. How did that come about?

I’ve been the music supervisor on most of my films. Music is my background. That was my training, not film. I never went to film school.

But music taught me so much. It’s really a part of storytelling. And so when I was pulling music from a list, you work with with spec tracks, like just temp tracks, like I’ve done in a lot of my work, it’s a great way to save money. I was pulling the music that I liked for the different sequences, but then I knew that [Jimmie Kirkpatrick’s son] JJ played trumpet professionally. And my son Luke [Enyeart] is a professional guitarist.

They really are that talented that they can do pretty much anything. Not only are they great composers and musicians, but they both have a very high emotional IQ. And you need to in this business if you’re going to hit people in the heart and really tell the story in a way that touches people. Jimmie’s son did the end credits and I wanted to have something that was a little jazzy, a little something that was cool but hopeful, so we could just soak in what we’ve experienced.

I wanted it to be a little more reverent, and what he did was perfect. Then what Luke did in the opening sequence was fabulous, so they’re my bookends: I’ve got Luke doing the opening and JJ doing the closing. Having the knowledge of this story being passed down to another generation and bringing that generation into the shared retelling and understanding of that story is something I didn’t want to overlook. I think our young are so talented.

As I was watching the film I was thinking about the basics of the story taking place in North Carolina, where the state legislature advanced an “anti-Critical Race Theory law” for its public schools, which could prohibit teachers from including films like A Binding Truth in their curricula.

So far, Province Day School has reached out: they are K-12 and they’re thrilled to screen it in February. University of the South wants to do a big screening of it. Queens University. Myers Park wants to as well.

So far, I haven’t seen any resistance to the film. It kind of threads the needle. When you’re showing an authentic story straight from the voices of those it happened to, you’re not trying to create a bias. Because of who these two guys, Jimmie and De, are, because of the way they are, the way they handle their own story, it’s just not offensive. Teachers don’t seem to be intimidated by it or thrown by it. If anything, I’ve got museums and libraries calling me in Charlotte. So I don’t see any issue yet.

I really hope the film gets seen by as many people as possible, young and old.

I think what this film for me is about is putting it out there and letting people feel however they wish. And maybe have a conversation about what they saw, what they felt, what they related to, what they want to learn more about. Because I think the Jimmy and De story and the other characters in the film present themselves in a way that is just real. They’re human, and we can all connect with something in the film.

I think their story is pretty universal. It isn’t just about race. It isn’t just about slavery. It’s about trust. It’s about friendship. It’s about supporting others. I wanted to make a story that could touch people’s lives and maybe make them think.

It was totally evident to me today that that’s exactly what the film is going to do: touch people’s lives and make people think. Congratulations—I’m wishing the best for it.

Thank you.