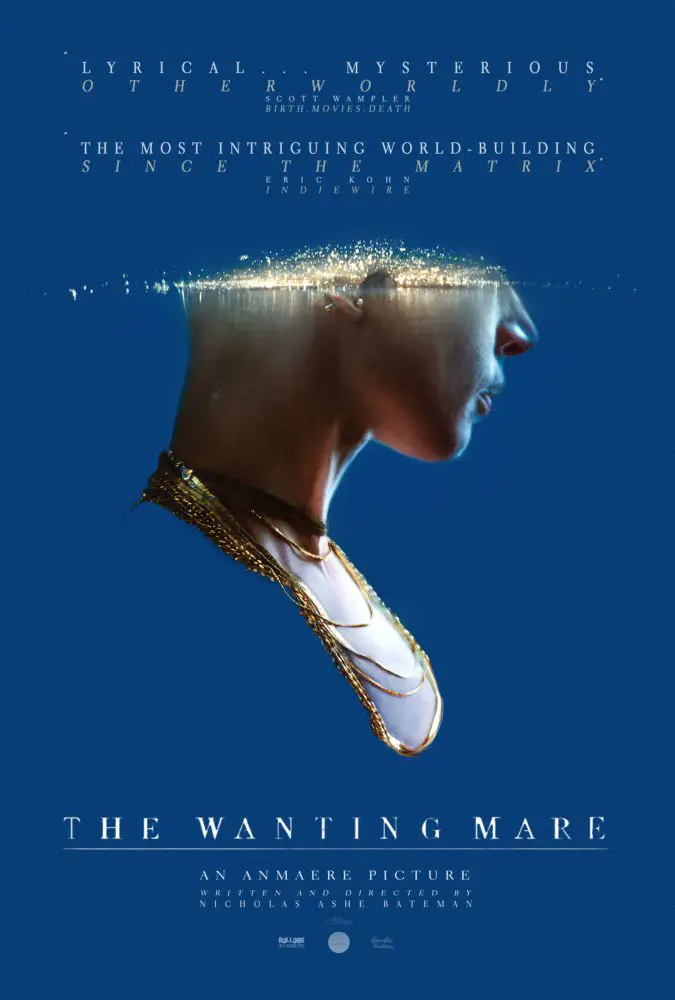

The Wanting Mare has been described as “a visionary work, blending science fiction, drama, fantasy and romance in lyrical style to create a bold and atmospheric new cinematic world”, so the opportunity to interview the writer-director was one I had to snap up.

The Wanting Mare is the directorial debut of Nicolas Ashe Bateman, a visual effects artist known for his work on A24’s The Green Knight, so I started by asking him what was it like to move from painting pictures for someone else to putting his own story there on the screen? “Well, that was always the hope,” he said. “Admittedly a lot of my experience before this was limited—or stunted, rather—as any of the opportunities of visual effects in the last couple of years were only as a result of diving into this movie with nowhere near the skillset required to finish it. A lot came after, when I was like ‘I guess we’ll have to figure out how to do some visual effects!’. The intention was always to figure out a way to be around people who were making movies: I didn’t go to film school, and I knew I was interested in visual effects, so offering to be an intern, do some free work seemed to always take me into visual effects. But it was always with the hope to make this movie in the long run, and just learn what I could along the way. That’s why it took five years to make The Wanting Mare: I didn’t know enough to make it at first.”

Considering Nicholas had learned so much by doing, I asked him if there was anything he would do differently if he was to start the project now. “No, I think that would be cheating,” he laughed. “There were a lot of hard lessons that needed to be learned, in wonderful ways, and no matter what happens, if I’m lucky enough to keep making movies, this one will always be a profound adventure with a few people in oblivion trying to make something; and then somehow getting to talk to people like you at the end of it. It’s going to take a lifetime to unpack, I think.”

I steered round his philosophical stance with a different approach, and asked whether Nicholas had any lessons to share with other newcomers to filmmaking. “Yes: treat the people you work with well,” he said. “Very few people were involved in making this movie, and we made a very ambitious movie. I didn’t make the movie alone, and it was made (and made better) by other people in a very small group. We all took care of each other for years in the lead up to the movie and during its making, and I think there’s real trust and love, and pushing forwards in the end product. That’s all there is: other people. Well that and the millions of people who said ‘don’t waste your life making this movie’! So treat people well, and keep going: those are my constant thoughts that I’d pass on.”

So the team is key, and so is understanding who to listen to. Those principles clearly paid off: it’s clear that Nicholas is very happy with the result.

Moving on to the visual side of the work, I commented that a great deal of the film looks as though it was made on real sets but actually involved creating locations almost out of nothing. So (excusing my ignorance), I asked why more “real sets” weren’t used. “Well, we didn’t have the money,” Nicholas said plainly. Does that mean it’s cheaper to do digital work than find or build a set? “Well, I think that’s what’s strange about the film: it’s in no way cheaper to do digital work. However, if that digital work is done by three people over five years, who make no money and don’t live normal lives, then yes, it’s actually cheaper. And that’s the path we decided to go for. But at a certain point, it transcends being just visual effects work; and I think certainly now that I’m doing professional visual effects work for others, the experience doing this was so different. It’s closer to world-painting than anything, just making many images that move you.”

Nicholas had mentioned being someone who thinks visually; and personally I’m the opposite, so I couldn’t quite imagine what it would be like. I had noticed there seemed to be a rather sepia colour scheme in a lot of the film and wondered how deliberate that was; I asked him whether his chosen colours become part of the design subconsciously, or whether there specific effort in that. “It’s entirely subconscious,” Nicholas said, “and to a painful level. Often, in the process of making the movie, essentially in chapters, we kept saying ‘let’s try a new colour’, but it wasn’t that easy. The film was made instinctually, and all our desires to do other things with it just came back to my favourite colours that appear when I close my eyes. And I think that’s what the film is: it’s sort of a subconscious dream, so it certainly has a limited palette.”

“A subconscious dream” is an interesting phrase to raise, certainly. I had wondered whether there was a message in the story about dreams; or perhaps something about mothers. I asked Nicholas whether he had intended a message at all, or if it was simply a daydream of his in the form of a film. “I think it is a dream about time and I don’t know if it’s projected forward or projected back; but it was certainly me in my early twenties making something and thinking about what aging would be like, and refuting the idea that there is some great boundary. There isn’t much exposition or links between the various pieces of things that have happened; the older versions and younger versions are essentially the same, and they were just there. Whatever this dream is, it’s about time going very quickly and us not having enough of it; and all those strange things that happen, like finding people.”

And horses, don’t forget!

“Yes, horses! There’s a bunch of places that horses come from,” Nicholas said, musing; “and I think I probably don’t know too many of them. But at a certain point in putting all this together, like the colours, horses started to come through. Horses mean a lot to different people, and they certainly seem to be messengers of a past for us; so they worked out well in the story, showing up to say ‘the past is still here’.”

I had to ask whether Nicholas could offer any explanation about the title, The Wanting Mare. “Well I love double entendres,” he said, “and I love double double entendres, which The Wanting Mare certainly is. I’m not entirely sure where the title came from, but it is one of the ideas I started with. I love words, and sometimes fall in love with the way they look together; ‘Wuthering Heights’ are probably my two favourite words together. So I know consciously it is certainly an attempt—with both the sound and visual appearance of the words—to mirror that phrase. Certainly The Wanting Mare could be read in maybe ten different ways, and I think they’re all accurate with many versions of ‘wanting’ and many versions of ‘mare’; but I tend closest to ‘mare’ of nightmares and dreams.”

I asked Nicholas, as the writer of The Wanting Mare (as well as director), to tell me about the world-building process. “I think in the past decade, if not more, I’ve been building this world which I’ve called Anmaere, a large fictional world. And in that large fictional world, there is one single history with events, places and people. The Wanting Mare isn’t really part of that world, in the sense that it’s almost sectioned off and you don’t really know what’s going on; there’s no context, there aren’t politicians; it’s almost a dream of someone in that place. So the world-building in The Wanting Mare, kind of like Wuthering Heights, is more about the feel of the characters in the story and less about the place. It’s not like I’d invented a place and then here’s what’s going to happen because of the specifics of that place; the wars, the Ken Burns ‘effect’ of civilisation. This is more about deciding a character feels this way, and therefore their house looks this way, and the topology of the place will… it all becomes one thing.”

The Wanting Mare struck me as a most individual work, and so I was interested to ask Nicholas what filmmakers he felt inspired his work. “On one end, I love the visual innovators: Peter Jackson, George Lucas, that sort of people. On the other, David Lynch and Ingmar Bergman, Tarkovsky… then there’s a third end, because I also love popcorn movies.” There are films out there for every mood, after all.

I asked Nicholas what he has lined up next. “I’m working on a continuous story on another part of the map, which is sort of the inverse of this. The world-building in The Wanting Mare comes from the characters, while the traditional sort of world-building starts with what’s going on in the world, and then the characters and their relationship with each other: that’s where I’m going to next, almost a post-war epic about these people growing up in a city. It’s probably going to be more affected by period than The Wanting Mare; that’s a little hard to pinpoint, and I like that. My interest is sort of a mid-century myth, and I’m going to try to carve out more spaces within that; so it might feel a little bit like the early sixties, and there are echoes of our world’s history with challenging, complex events.”

It will be interesting to see how stories connect, or perhaps don’t connect, depending how thing turn out. In the meantime, The Wanting Mare is available to rent or own on digital HD on 7 February 2022; look out for it if the trailer below—or this conversation—has caught your interest.