Who might, one has to wonder, be the audience intended for A Little White Lie? Kate Hudson fans who miss her adorable rom-com turns? The Don Johnson fan club, wondering where their roguish crush has disappeared to? Those looking for a Knives-Out style comedic mystery? (After all, Hudson, Johnson, and co-star Michael Shannon have all featured in that sparkly franchise.) Or perhaps admirers of the canny 2017 Chris Belden novel Shriver, upon which Michael Maren’s screenplay is based?

Maybe, like me, a viewer might be attracted to the film’s academic setting: I spent a lifetime on campus, in English departments, where careers hinge on publications, reputations, and achievements at least a little like the literary conference scheduled to take place at the start of A Little White Lie. But academics are likely to find this film as disappointing as will any of its stars’ fans or even those streamer-scrollers just hoping for a little light fish-out-of-water comedy. Maren, who also directed, has managed even with an appealing cast to squeeze the spark out of Belden’s novel, reducing its characters to shallow stereotypes whose agendas are just enough at odds with each other to create some narrative friction.

A Little White Lie, as one might guess from its title, begins with one. English department head and novelist-turned-program-administrator Simone Cleary (Hudson) is faced with bad news: her college president (Kate Linder) is cutting funding for the school’s annual literary festival, a yearly drain on scant resources. There’s only one chance at its continuation: bringing in a big-name star, one who can pack their auditoriums, liven up their panels, and raise the prestige of their tiny Midwestern liberal-arts college’s fading profile.

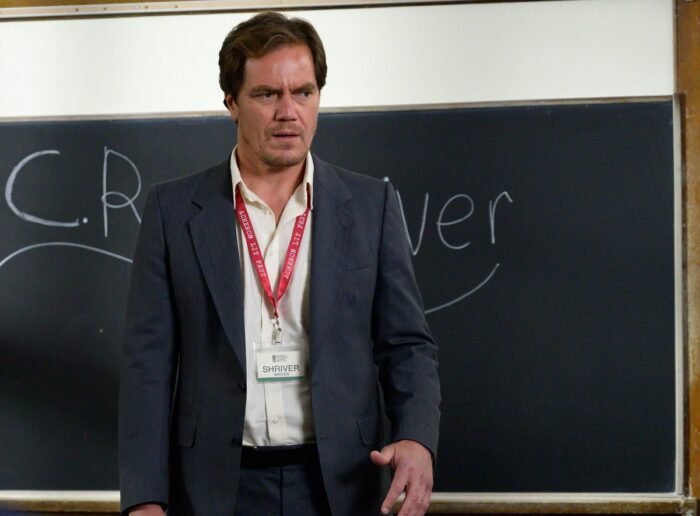

Cleary has been trying for years to contact reclusive author C.R. Shriver, a Salinger type who’s disappeared from public view for 20 years after his one great novel, Goat Time. And just in the nick of time, after dozens of failed attempts, she receives a reply: the missing author will indeed attend her upcoming festival, just the news she needed to save her pet project and department’s reputation. There is, of course, one problem, the “little white lie” told by her correspondent: her “Shriver” is no novelist at all, just a down-on-his-luck handyman (Shannon) by the same name who’s been receiving Cleary’s mis-addressed missives and decides—though he has never read Goat Time, nor in fact any novel of any type, and certainly never written a lick—to impersonate the never-seen, long-missing author.

Impersonating a celebrated author turns out to have its own set of challenges for an unread man who never travels and does not even possess a credit card. He’ll have to read the novel he supposedly wrote, and maybe even write a little to read at the festival, although there’s nothing in his life to write about other than the water stain on the ceiling above the bed in his seedy apartment. And he’ll have to convince Dr. Cleary and her English department colleagues and graduate students of his literary credentials.

Fortunately for Shriver, those tend to be a gaggle of cretins who exist, it appears, only to lampoon the modern-day English faculty. Johnson plays a hard-drinking denim-clad cowboy type who rides a horse to campus because he’s no longer able to drive: late to the pivotal department meeting, he mansplains Shriver’s aesthetic to Cleary, ignorant that she wrote the article he’s scuffling to remember. M. Emmet Walsh is a doddering old senior professor who can’t recall much other than that John Updike once attended the festival. (Updike, whose literary career began in the 1950s, last attended such a festival in the 1990s, shortly before his death at 76.)

The other creatives and academics surrounding the festival are no more roundly depicted. Aja Naomi King plays a lesbian author whose only purpose seems to be to challenge Shriver’s no-longer-viable patriarchal privilege; she’s saddled with a cake sculptor of a partner for nothing more than a running gag. Da’Vine Joy Randolph plays a visiting writer desperate to get Shriver’s attention. Wendie Malick, a local donor who’s had her way with more than a few celebrated authors, is desperate for something else of Shriver’s; so too is Zach Braff in a way. Poor Peyton List shows up in a bikini for no reason at all other than to distract Shriver with her youth and beauty in a role that will surely suffer comparison to Mena Suvari’s in American Beauty.

Is any of this funny yet?

Unfortunately, no. And in a narrative sense, there’s really no one to root for, either. Belden’s novel employed Shriver as its point-of-view character, using the limited filter perspective to show his thoughts on the page, unfolding in increasing panic as his ruse is jeopardized at each turn of events. And so, over time, one comes to know, even like the man, despite his ill-advised jig masquerading as a celebrated author. Maren’s film doesn’t really ever come to know the character, and Michael Shannon—though he is good at what he does—largely just squints and stumbles his way from one scene to the next without any emotion other than a general sense of confusion and disbelief. In ten pages, Belden’s novel provides a deeper characterization of the protagonist than does Maren’s whole film.

Hudson’s Cleary fares a bit better: she, at least, is grounded, empathetic, professional, eager to prove herself. As a woman in academia, she has to, over and over again, through the own excellent novels she’d authored before giving her life over to administration, through managing the herd-of-cats faculty in her department, and while still actively publishing criticism. She seems in many ways, frankly, too smart to be duped by Shriver’s disorganized ruse. And, sadly, the supporting characters serve no real purpose other than what Maren sees as the occasional joke at their expense. In sum, A Little White Lie‘s depiction of a modern liberal arts university is one where one-dimensional stereotypes jockey for what little pieces of pie they can: the lower the stakes, the louder the struggle.

Belden’s novel is on the surface more overtly absurd, with character names like Cleverly (not Cleary), Delta Malarkey-Jones (not just Delta Jones), and T. Wätzcesnam (pronounced “Whats-his-name”). Yet it is also far more empathetic. While each of Belden’s characters are of a type, they are not limited to that type, and by its conclusion, one finds nearly all of them sympathetic and multidimensional. In tamping down some of Belden’s absurdities, Maren seems to have neutered the narrative, making it less funny and less insightful. There’s nothing wrong with abandoning subplots and truncating events: most adaptations do so. Belden’s novel, still, is a sprightly four-hour read, and what seems sacrificed in Maren’s script is largely depth and meaning.

It’s possible, of course, to mine this territory of academia’s foibles well. Campus novels have done so, with excellent reviews if often a limited readership, since the 1950s. Films like 2000’s Wonder Boys (directed by Curtis Hanson from Michael Chabon’s novel), though it bombed at the box office, and 2006’s Stranger than Fiction (directed by Marc Forster from a film by Zach Helm) both managed plenty of laughs while offering insight into the ebb and flow of literary creativity. In those films, creative types were actual people, not just types. And Belden’s novel, even for a slim and largely absurdist comic romp, still managed to find something of merit to say about the impostor syndromes and writers’ blocks that can stall already-precarious academic careers.

With its excellent cast and promising source material, A Little White Lie would seem like it could appeal to almost anyone: fans of its stars, readers of Belden’s novel, anyone who’s spent time in or around an English department. Sadly, with the life and spirit squeezed out from its screenplay and its stars mostly left hanging by a script lacking characterization, A Little White Lie consists of little more than a few modest laughs strung together in search of a story.

Directed and written by Michael Maren and based on the book Shriver by Chris Belden, A Little White Lie opens in theatres and on digital and on demand March 3, 2023. Starring Michael Shannon, Kate Hudson, Zach Braff, Kate Linder, Aja Naomi King, with Da’Vine Joy Randolph and Don Johnson. Rated R for language.