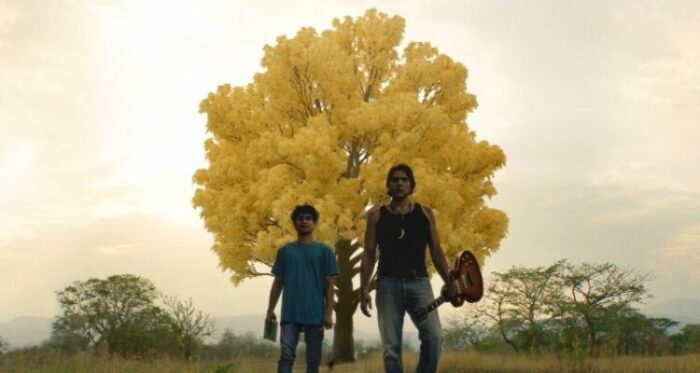

Say this for The Shadow of the Sun (La Sombra del Sol): its intentions are honorable and its casting and performances authentic. It is, after all, a film set in a contemporary Venezuela where social problems are rampant: economic inequality, homophobia, ableism, and street violence among them. Its story—about brotherhood and following one’s dreams—is one of optimism and hope. Its two leads are adroitly, carefully cast: Anyelo Lopez, one of the first deaf actors to lead a Venezuelan film, plays Alex, a bright if directionless young man; Carlos Manuel Gonzales plays Leo, his estranged older brother, a construction worker whose glory days are behind him.

The film’s plot is, aside from the details, pretty conventional, one that’s been around the cinema since the days of Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland: “Let’s put on a show.” Both Alex and Leo are facing economic hardship. Their parents long dead, Leo scuffs about between jobs while eking out at best a meager existence, and the younger, more intellectual Alex has dreams but no real opportunities. Alex hits upon the solution: he’ll write a song and submit it to the nationwide star-search in hopes of winning a cash prize. (Never mind it will be his first effort.)

And so, Alex enlists Leo to perform that yet-to-be-composed song for him. That Alex is deaf and that he has never written a song before are just two of the many obstacles in their way. Leo has to earn a living to pay the rent for himself and his live-in girlfriend Yolanda (Greisy Mena): his days as a singer are long behind him, and he was never much of a guitarist anyway. He needs to cobble together some willing mates (a sequence that involves a daughter having exhumed a guitar from her father’s grave) and a place to practice. It’s a lot of effort and time from people who can’t necessarily afford much of either to dedicate to Alex’s nascent quest.

As one might imagine with any such narrative, The Shadow of the Sun invests itself in some pretty generic scenes. Leo and Alex build a ramshackle practice facility. The bandmates practice, though not without conflict. Yolanda argues with Leo about the money he’s not earning—and about Alex. Most of these look and feel as generic as they sound: montage sequences of activity are set to a cloying, repetitive score from Sandro Morales Santoro and always run longer than necessary to make the point; the girlfriend character exists only to emasculate Leo and harass Alex. The band scenes are surprisingly lifeless in their interactions, yet it doesn’t matter in the long run as their presence and purpose are largely abandoned by the film’s climax.

When it’s not succumbing to the clichés of the genre, The Shadow of the Sun finds itself on firmer ground. As Alex, Perez knows deafness well, and some scenes employ a sound design that presents his perception of the world and of Leo and the band’s performance. Alex’s signing with Leo and interactions with other characters render the daily grind of life he faces with his disability: the abled make assumptions about his intellect and speak of him as though he is not even present. Films like this, with the presence and talent of actors like Lopez, provide a necessary corrective to the longstanding practice of having able-bodied actors pretend to disability.

Also strong is the film’s characterization of Leo as a man ground down by economic disparity. He’s talented, intelligent, charismatic, and hardworking, but he can’t quite seem to earn a wage sufficient to guarantee his livelihood (or satisfy his scold of a girlfriend). Some, dealt that hand, turn to violence or crime, others to drink and drugs, many, today, to the false hope of racist nationalism and conspiracy theory. Gonzales’ Leo is not one of those. He’s sensitive, acutely aware of his own failures, and determined, even though logic probably dictates otherwise, to help his little brother achieve his dreams. (And to his credit, Gonzales learned Venezuelan Sign for his role and for his collaboration with his co-star.)

As the deaf songwriter pursues his quest, the film makes a parallel between Alex’s quest and that of provincial Acarigua: director and co-writer Miguel Ángel Ferrer makes it clear that Alex’s is a story to be heard as is Venezuela’s. It’s not a subtle point: the screenplay (co-written by Guillermo de la Rosa) makes such abundantly clear. The film’s production accounted for nearly 200 jobs in Venezuela and employed six deaf actors, including Lopez, who was discovered through an extensive national casting process and who appears in his film debut.

When the film reaches its climax at the “Caracas Magic” competition, we viewers never get to hear what Alex has composed or what Leo performs. Perhaps there is a point to be made there about Alex’s deafness. But what we do hear is more of the same overworked saccharine score that plays throughout so much of The Shadow of the Sun, so if there were some intent to render Alex’s subjectivity during this important moment, it’s one that’s deeply compromised. It’s hard not to wish for a performance of the composition so important that the whole narrative is centered on it and the film titled for it.

The Shadow of the Sun is a film with much to root for. To its championing the impoverished, the disabled, the emasculated, and the powerless, add the queer: it is to the film’s credit that Alex’s being gay is a part of what drives his art and makes him doubly a target of abuse. But a largely-unnecessary coming-out scene after the climax feels simply tacked on. (One can, after all, craft a compelling storyline about queer youth without such a scene, as is the case in the Argentinian drama Sublime.)

Even with two convincing lead performances and all the very best of intentions, The Shadow of the Sun slips into cliché too often to satisfy fully. More than a few viewers will groan, not chuckle, at some of the gags, and wince, not sob, at its emotional scenes. Some of Leo’s grand gestures seem like they were borrowed from a rom-com, not a street drama. The film was voted, though not without some controversy, Venezuela’s official nomination for the International Feature Film competition at the 96th edition of the Academy Awards®, and it is enjoying a receptive festival run, winning the Best Latin American Film Award at the Monterrey Film Festival in Mexico and the Best International Film Award at the Georgia Latino Film Festival.

The Shadow of the Sun will screen on Sunday, November 26 at Museum of the Moving Image in New York City as part of Cinema Tropical’s ‘Las Premieres’ series as well as at other festivals and screenings throughout December.