“I am fine” is the English translation of Io Sto Bene. It’s one of those phrases used to dismiss, rather than engage, a sincere inquiry. People say “I am fine” often when they aren’t, or when they’re unsure. It’s a way of keeping others at a bit of remove, a polite distance. In the case of Luxembourgian director Donatto Rotunno’s film Io Sto Bene, his country’s official Oscar submission last year premiering this week on the streaming and video on demand service IndiePix Limited, the phrase is a line uttered by its protagonist to a young woman on their first meeting. “Io sto bene,” he tells her, he’s fine, but clearly, he isn’t; he’s living a life wracked by loneliness and regret.

Rotunno’s film is in the same way bene, or “fine.” It’s marvelously acted, well-photographed, and carefully edited with an affecting musical score, a pleasant if understated melodrama of a potential companionship between an aged man and a young woman. It’s fine all around, and yet lacking something ineffable, any certain je nais se quois that would make its presentation more memorable. While Io Sto Bene is without doubt fine in every regard, it’s also a film that never quite transcends its glistening competence to become memorable, instead staying in its lane as a humble, quiet, unremarkable tale of intergenerational friendship.

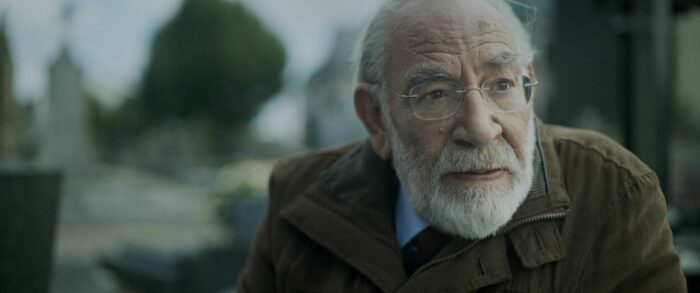

In the film’s present, Antonio (Renato Carpentieri) lives in Luxembourg, where he has spent nearly his entire adult life. His Italian homeland is a distant memory, one he left long ago. Recently widowed and newly retired, his life has become one of nodding politely at retirement awards, selling the house he and his wife had shared, and evaluating nursing homes for the next stage of life. It’s not much to look forward to. Antonio’s emotional life, it seems, is all in his past, especially the long marriage he enjoyed with Mady (Marie Jung), whose energy and vitality helped account for the couple’s success in life, love, and business.

A minor car crash—a fender-bender implying Antonio’s now too old to be trusted to drive—brings a young woman into his life. “Io sto bene” he tells her when she finds Antonio knocked out at the wheel. She assists him and the two strike up an unlikely friendship. She, Leo (Sara Serraiocco) works as a DJ and aspires to a more multimedia artistry, but she has her own struggles. She lives in a one-bedroom flat in above the club she performs in and she’s pregnant by a man she won’t tell of her situation. Worse, she has to fend off the advances and threats of her grubby club manager, and she seems alienated from nearly everyone and everything except the musical raves she creates.

Rotunno draws these characters with fine strokes. It seems perfectly rational that the two might find, in their loneliness, a companionship. Antonio seems something of his late wife Mady in the younger Leo, though nothing about the relationship seems at all improper. Antionio needs someone to talk to; Leo would certainly benefit from some life experience and gentle guidance, or at least a sympathetic ear. Scenes of the two, together and apart, are the best in the film, whether Antonio is ruing his lost love or Leo is bringing down the house with her visual-artistry DJing.

There is, though, another timeline, one far in the past, as Antonio left Italy for Luxembourg. (Most of these are prompted by letters Antonio wrote to his father with the words “Io sto bene.”) Alessio Lapice plays a decades-earlier Antonio whose relationship with his two cousins, Vito (Vittorio Nastri) and Giuseppe (Maziar Firouzi), and their romantic relationships. This younger version romances Mady (Marie Jung) and finds himself a little too involved in his cousins’ affairs. But the events of this timeline, while not in and of themselves uninteresting, seem to have little to do with the narrative present save for that they happened to the same character. Certainly, it’s possible to juggle multiple timelines and actors in a cinematic narrative, but here the only real consequence of the past is that it takes screen time away from the far more intriguing present.

That’s a shame, because Leo’s situation—a talented artist living in near-squalor, pregnant without support, and subject to the abuse of her landlord—requires some real attention. The older Antonio might not be in a position to offer anything but friendship, but their platonic, intergenerational, and very realistic relationship feels like the core of the film, and the frequent, at times unyielding, flashbacks offer more impediment than insight to the characters. Serraiocco and Carpentieri are also both excellent in the roles, and I wish only they’d been entrusted to the let their narrative play out in full.

Even so, Io Sto Bene is, for what it is … fine.

Written and directed by Donato Rotunno, Io Sto Bene (2020 debuts September 15, 2023 on IndiePix. 99 minutes, in Italian, Luxembourgish, English, and French with English subtitles.