Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams—based on Sara Varon’s graphic novel of the same title—is an oddly unique yet deeply welcome piece of new representation for a few fading breeds of film. It’s at once a completely dialogue-free silent film of sorts, while also being one of the few hand-animated feature films to make meaningful success in the mainstream in an era of post-Princess-and-the-Frog-Disney, where the direly needed, continued survival of companies like Studio Ghibli and Cartoon Saloon has never been more essential. With its release several months after its nomination for Best Animated Feature at the 2024 Academy Awards, the Neon-distributed, Spanish-French co-produced film finds sincere power in its tale of friendship. The film’s marvelous narrative construction is solely dependent on the visual language of its animal-inhabited Manhattan, incredibly distinct characterization, and a deep platonic soulfulness rarely rivaled even in most of its CGI-built contemporaries.

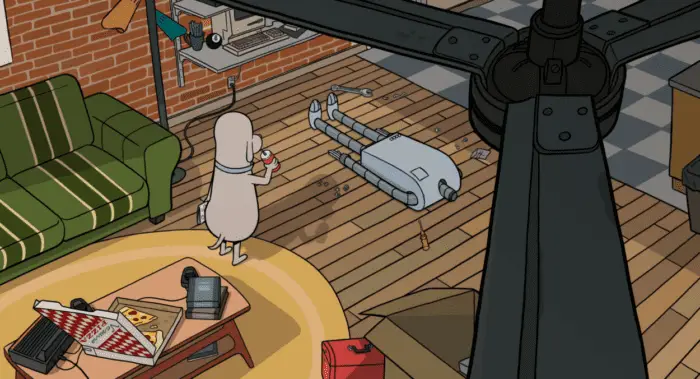

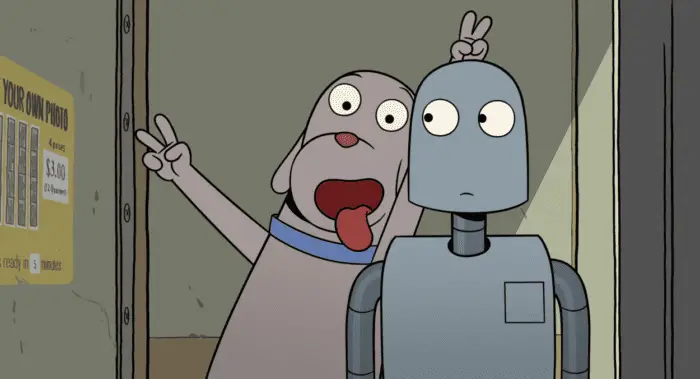

Robot Dreams‘ story is effectively a modern fable; Dog is a lonely New York resident in the 1980s whose days are largely spent in front of an uninteresting television feed, playing Pong all by himself while yearningly observing the companionship of his neighbors. When a specific advertisement for a robot companion suddenly hits Dog’s television feed, however, he immediately takes the offer and buys it—leading to the arrival of Robot on his doorstep, whom Dog successfully assembles. As the two of them romp around New York City together over the course of the next several days, their bond grows deeper, exploring just about everything that the city has to offer… until a swimming-packed visit to the beach on its last open day of the summer leads to an accidental malfunction with Robot that rusts him in place. A crestfallen Dog is forced to leave Robot on the beach for the night, and eventually, almost an entire year.

Dog resolves to return to Robot once the beach reopens, but a series of mishaps on their individual journeys leads to continued separation. Robot Dreams evolves into a deeply felt tale of loneliness and yearning, the alternate paths we take beyond any of our expectations, and what it means for us to chart lives independent of those we thought we would have continuous bonds with. Yes, this is a film whose visual aesthetic, dialogue-less charm, and anthropomorphized creatures will certainly allow for immediate appeal to audiences of all ages. But the maturity, wisdom, and lived-in melancholy of its Earth, Wind, and Fire-laden tale—whose anniversary “September” is a recurring motif of the film, and whose treatise on memory and fleeting connection is replicated with great faithfulness in Robot Dreams—is the primary quality that will have adult audiences resonating profoundly with its sheer emotional authenticity.

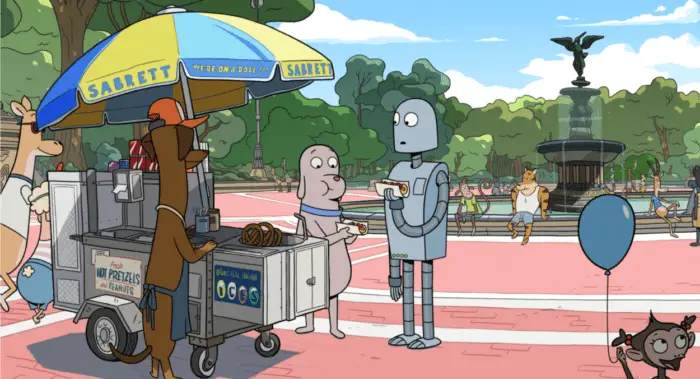

With the sole exception of the fact that every single one of its civilians are animals of all kinds of species, the Manhattan that Robot Dreams presents is almost exactly like what’s there today. Perhaps the most immediate thing about the film is that one of its primary aims is to serve as an ode to the city, especially when Robot and Dog are exploring it with great enthusiasm. There’s a liveliness in the way the film draws into shining life New York’s parks, the deep annoyance of its endless line of traffic, the busker music playing throughout its streets and subways, the griminess of its second-rate shops and back-alley dealings, the restaurants and shops lined along just about all of the edges of the beach, and the list continues in ways that I’m sure New York’s own residents can attest to more faithfully. The balance this film manages to aesthetically strike is a delicate one; the creatures and machines it features need to be simple enough to be charming along with their distinct presentations and personalities, while the city they inhabit needs to be realistic enough to be familiar, but not so much that it clashes with the simplicity of its inhabitants.

As a result, Robot Dreams isn’t even a film that grounds itself completely in our waking reality. There’s an clear mix here, in that the strict realities of rusting after metal’s prolonged exposure to water are not at all struck from the film’s list of possibilities, but there’s also not a single human that ever shows up in any capacity whatsoever. In that same spirit, Robot Dreams is as much about the literal dreams we imagine in order to sustain us through utterly profound longing, and as far as Berger is concerned, there are absolutely no limits to what those dreams can entail. From imagined reunions between Robot and Dog following their separation, to fantastical encounters with enlivened snowmen, all the way to tap-dancing-flower-sequences pulling imagery straight from The Wizard of Oz, each dream takes continued leaps in symbolic representation that further deepen the associations we draw between the animal-and-mechanical characters, as well as their eminently human experiences and emotions. Not all of it is airtight—some of them might be just a bit too far-fetched and out-there for their own good—but the suspension of disbelief inherent in the film’s premise is enough to allow great flexibility for audiences to simply enjoy the film’s animation prowess on its own merits.

Robot Dreams‘ wisdom and emotional sagacity is never truly defined by a single groundbreaking moment over the course of its story, which may just as well be its most potent trait. There’s a fundamental understanding here that life-changing revelations about the ways we define our connections come about as a result of an accumulation of multiple key events in our lives, and Berger works in service of making that accumulation as both joyful and mournful as possible. Dog and Robot’s separation prompts profound grief between both of them, to be clear, but life does not simply stop for either of them just because their bond comes to an ostensibly temporary close. For one, Dog’s imagined friendships make way to attempts at connection, which then turn into other meaningful friendships with those he finds along the way; Robot’s immobility nearly drives him mad after he’s frozen in place for the winter, but it also makes him the perfect location for a burgeoning family of birds who take him for a great nesting spot.

There’s been a recent influx of films with fixations how we define our lives through what’s unlived and unspoken, from Everything Everywhere All at Once‘s multiverse of untapped potential, to All of Us Strangers‘ meditations on gay life and grief, to I Saw the TV Glow‘s abjectly paralyzing exploration of gender dysphoria. But perhaps the closest analogue to Robot Dreams‘ mature fable on longing and friendship has to be Celine Song’s Past Lives, a film that touches on unexplored connections and providence through a burgeoning-yet-cut-short love story, whose distinct uniqueness is in how that then serves as a framing device for Korean immigrant identities. That film also contains deeply moving insight and melancholy about the ways we create lives beyond the bonds that could have existed, exploring what it means to try to revisit those bonds when we’ve since changed ourselves in ways that mean just as much as what was there prior.

To see those traits then replicated and recontextualized in a 2D-animated film with anthropomorphized animals and automatons whose focus is more on platonic bonds—a subversion of the typical mass-produced animated feature you’d expect from the likes of Illumination—is so striking that it’s a deep testament to the animated medium’s unique strengths. Which ultimately then begs the question; what is it about fables that draw us to them, and what makes this one so especially different? We conceptualize clear-cut morals from tales of animals and archetypal figures, most of which fail to account for the complexity of our interactions with others, and what we do for the sakes of ourselves and the ones we love. Yet Robot Dreams expands on that foundation to place those archetypes and creatures in an actual human city, itself a gesture of setting that points at its aspiration to defy clear-cut answers for both our most quotidian and profound bonds. The rest of the film and the eloquent honesty of emotion it displays makes one thing clear; humans (and human speech) need not apply for a film to speak to our humanity.