The Beach Boys endless summer continues to shine. The latest documentary delving into the California saga of these career crooners features little overcast. While that sunny nature keeps things light, the lack of stormy weather misses a few honest points about the musicians’ history. Consequently, though entertainingly informative, The Beach Boys glaring omission of certain moments makes this more of a primer than a closer look.

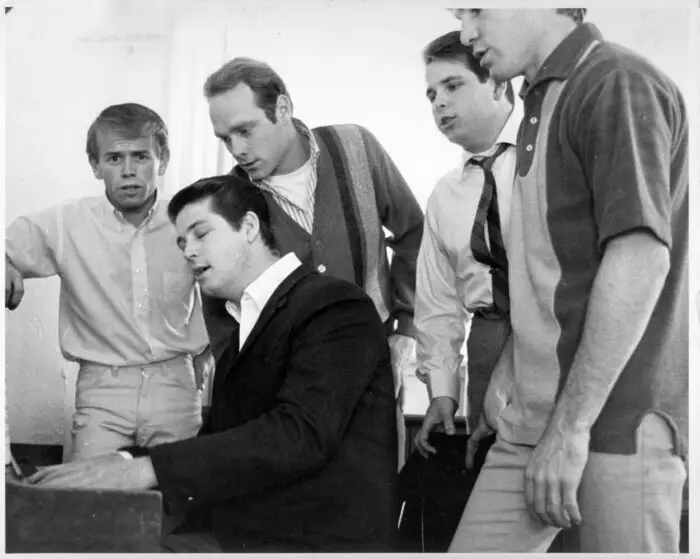

The Disney documentary explores the legendary musicians known as The Beach Boys. It begins with a humble origin story of family and friends bonded by a love of music. Where it goes, however, is down a thorny trail of genius, stress, strain, and fracture. Yet, as a fellow once wrote, all’s well that ends well.

In many ways, The Beach Boys is more celebration than examination. Unlike documentaries such as Moonage Daydream (2022) with its cinéma verité collage of archival footage, this is a series of interviews with the surviving band members talking about their past. That can make things seem one-sided, although age has certainly made them confessional in ways that aren’t always flattering. Al Jardine, for instance, admits to mistakes he regrets, while also expressing the honest fact nothing can be done about them now.

Yet that’s as melancholy as the film ever gets. Someone suggests a misstep then shrugs their shoulders before the story moves on to rosier territory. As such, The Beach Boys starts as a look at humble roots but when it nears the predictable rock ‘n’ roll minefields, any calamities are decidedly PG. Perhaps the only thing ever really touched on with any significance is the abusive nature of Murry Wilson, father, uncle, and manager to the many young men in the band.

Arguably these omissions may be because the documentary isn’t concerned with the lives of the legendary Beach Boys. Its focus is more on their music. One might argue the two are invariably linked, but this film would seem inclined to the contrary. The only time it really suggests the events of anyone’s life are tied to the songs is when The Beach Boys mentions Brian Wilson’s desire to break out of the mold that confined the band. Exploring the album Pet Sounds requires mentioning such dissatisfaction while moments like the acclaimed musician being trapped in bed due to mental illness get passing remarks. Similarly, there’s the recognition of a cultural shift that made their image less popular but little about the various members’ feelings regarding the counterculture movement at the time. It’s like the documentary only mentions bummer topics in passing, when necessary, before speeding to the next sunny stop.

In that respect, The Beach Boys is an intriguing look at the music which helped shape a scene. It’s impossible to imagine Sixties surf culture without their harmonious tones. That said, the documentary does do an interesting job of showing how a pop music paradigm shifts not simply because of a new sound but the mythology it embodies. The Beach Boys weren’t simply an innovation in style, they sold a notion of an idyllic endless summer vacation populated by sexy people racing in hot rods from one surf stop to the next.

Furthermore, the documentary solidly presents the string of influences which inspired now iconic tunes and albums. Various members of the band give credit to Chuck Berry, Dick Dale and the Del-tones, as well as The Four Freshmen while the film takes time to demonstrate their music so audiences can develop the audio connections. Similarly, there’s a whole segment about The Ronettes and Phil Spector’s wall of sound inspiring Brian Wilson.

The only time it gets kind of wonky is when one interviewee makes the moronic suggestion that the competitive clash for album sales with The Beatles should be thought of as a collaboration. Instead of musicians fighting for chart dominance by outdoing one another, history should regard this as indirect inspiration to do better. It’s not just an overly rosy reinterpretation misrepresenting the past, it flies in the face of what the Beach Boys themselves say in the documentary. Whatever respect the two groups have for one another came years down the line.

But The Beach Boys is full of such moments as it ignores or breezes quickly by more uncomfortable topics. Perhaps the filmmakers felt too deep a dive into Brian Wilson’s mental health issues would derail the focus. In all fairness, those difficulties are better explored in Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times (1995). There’s also a staggering lack of attention paid to the alcoholism and tragic drowning of Dennis Wilson, who died broke, homeless, and estranged from his bandmates. It’s especially odd since, when it came to the surfer image the musicians presented, he was the only one actually living the lifestyle.

According to Fred Vail, “Dennis Wilson was the essence, the spirit of the Beach Boys.”

That quote isn’t from the film because there’s a shocking lack of contemporaries, friends, or family discussing anything. To a certain extent that may be because folks have passed away, but The Beach Boys settles for words from Ryan Tedder, one of the ten producers on Taylor Swift’s “1989”. Janelle Monáe’s contribution is interesting given she worked with Brian Wilson on her song “Dirty Computer”, but the film fails to drive home the legacy of the band. More than anything, this seems like a documentary meant to catch the attention of a fresh generation unfamiliar with The Beach Boys.

In that respect it works. The Beach Boys is a sunny celebration of the California sound and the myth it presented: beach blanket bliss where the party never stops and the worst that ever happens is a wipeout. Visually the film is dynamic with graphics and archival footage to keep things engaging. Though it consciously veers from sour notes, it’s never dishonest. It simply lacks a closer look at grimy facts. Still, The Beach Boys is a solid celebration of tunes and musicians who shaped pop culture to this day.