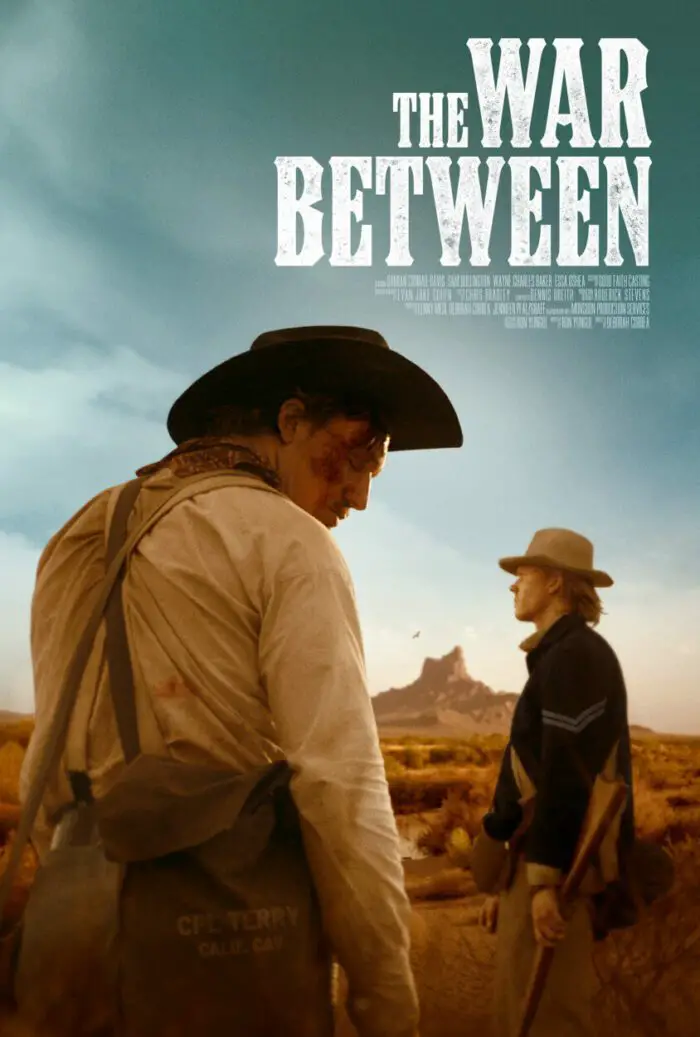

That the tentacular reach of the U.S. Civil War extended to the far West may be a surprise to some. In The War Between, a new historical drama channeling the imagery of John Ford and Howard Hawks’ Westerns, two soldiers on opposite sides of the war face off in the Sonoran desert of Arizona, where Confederate troops clashed with Californian volunteers. The feature-film debut from director Deborah Correa, The War Between looks back at a pivotal moment in America’s past, partly to better understand its thorny, equally contentious present.

The War Between opens in April, 1862 with a groggy Union officer, Israel Terry (Damian Conrad-Davis), slowly awakening, alone in the desert near Tucson’s Pichaco Peak and nursing a traumatic head wound that makes memory and travel difficult. Managing to crawl to a nearby river, Israel encounters a man named Moses (Sam Bullington), a Confederate private separated from his forces. Moses—Private Jennings—offers Israel some desperately needed first aid and protection. His memory addled and his mobility hampered, Israel grudgingly accepts Moses’ offer. To decline would mean likely death.

The two men make for convincing foils. Though he is drawn as a capable and dedicated soldier whose journals and drawings mark him as a man of intellect and accomplishment, Israel is compromised by his wounds and unfamiliar with the territory. Moses, a southerner, is by turns laconic and sardonic, as slow with his gait as he is quick with a quip. His story—being separated from his troop—is suspicious, yet Moses seems to know the land and the people: he can speak some Apache and is conversant with their ways and travels. Though Israel regards him with contempt, he knows Moses is key to his survival.

As they travel, the two spark a lively debate about the causes each serves, one that resonates with contemporary conflicts about race and equality. Moses’ allegiance to the Confederacy and 19th-century Manifest Destiny is presented more as a logical consequence of his upbringing than as a fault of his character; Israel’s to abolitionism more as an intellectual position than a personal virtue. The conflict between the two men is rich in meaning and fraught with tension as they travel, their destination uncertain, their path perilous in the harsh sun of the Sonoran desert.

The second act introduces a third character, an Indigenous man called The Great Seer (Wayne Charles Baker, whose voice and affect seems to lovingly channel that of Chief Dan George as Old Lodge Skins in Little Big Man). After a brief skirmish, The Seer joins Israel and Moses, both as their captive and as their guide and companion; he himself has his own quest he must fulfill. As the trio continue their slow traipse across the desert, where they will end up—at a Union garrison or a Confederate fort—becomes paramount. Neither of the two combatants knows for sure the status of his own troop’s success or whether either will be welcomed where and when they arrive.

In the film’s third act, the narrative yields to the story of two women, one the spokesperson for her tribe, the other a soldier’s wife hoping not to become a widow. The complexity of the story illustrates that the Civil War’s impacts were felt far and wide, as westward as Arizona and by American Indigenous peoples every bit as much as Union and Confederate soldiers, their wives, and their families. In that respect, writer and executive producer Ron Yungul’s script is both ambitious and commendable, layering The War Between with a slow-burn revelation—and several not-unwarranted surprises—as the men near their destination and the story its conclusion.

That complexity comes at the expense of the film’s narrative momentum, which flags a bit in its final act even as the cast and crew give the rich storytelling its due. Conrad-Davis and Bullington play off each other like a couple of wary, cagey wildcats, each of them the other’s equal in their very different intellects. Baker makes for a lovely, pithy contrast to the two of them. Left only to flashback, Tank Jones has little to do as Conrad-Davis’s friend and partner, his Atticus Cleveland existing primarily to characterize Israel as a white man who can befriend a Black man. Essa O’Shea, as Israel’s wife Charlotte, is introduced first in flashbacks as a sentimentalized war wife but gets her chance to shine in the final act’s narrative present. O’Shea also delivers a haunting, lilting performance of the film’s closing-credit song, the traditional “Johnny Has Gone a Soldier,’ arranged by the film’s composer Dennis Dreith, whose period-centric score provides a thematic richness throughout.

The film’s visual design is stunning. The War Between is the first to receive the state of Arizona’s tax incentive for film production, and director Correa, DP Evan Jake Cohen, and the production crew make the most of the Sonoran desert’s natural beauty and 19th-century interiors for a shoot that recalls, but never sentimentalizes, the old West: the harshness of the exteriors, the majesty of the landscapes, the grit and dirt of the desert all impact the characters who must traverse its dangers successfully—or die trying. Skirmishes and standoffs, the outbursts of gun violence that so often resolve narrative conflicts in Western films, are shot with an intensity and immediacy: their violence is sudden and startling, never gratuitous, yet always with consequence.

Also worth a final mention is Correa and her crew’s work with The Heroes Journey, a nonprofit dedicated to empowering service personnel, their families, and the families of the fallen through storytelling in cinema and other narrative arts, in the case of The War Between employing veterans on the cast and crew both. It’s a mission of Correa’s, whose past and future projects also focus on the courage and challenge of those who serve. More than another shoot-em-up legacy Western, The War Between honors those who fought by striving to understand and convey their circumstance, offering up—as the richest films in that oldest of American film genres can do—new and invigorating perspectives on a past we all continue to need to know.