Bringing Out the Dead proves that compassion can be gritty. Instead of another Taxi Driver (1976), confirming an audience’s desire to loathe the world, acclaimed director Martin Scorsese instead steered a script from Paul Schrader through notions of guilt, redemption, kindness, and choice. That last bit may have been why viewers didn’t seem to enjoy the film. Bringing Out the Dead shows how this world is made by people. Society isn’t something always-already given, its grotesqueries are our own construction.

The film stars Nicolas Cage as Frank Pierce. He’s a burnt-out paramedic on the verge of a total meltdown. Chasing the high of saving lives has warped Frank into a kind of junkie, and after failing to save a young woman named Rose, he’s haunted by her ghost. Currently on a lengthy losing streak, seemingly unable to prevent anyone from dying, Frank is falling apart. However, staring into the abyss means taking a hard look at the life he’s living as well as the motivations behind his actions.

Bringing Out the Dead is an adaptation of Joe Connelly’s semi-autobiographical novel. Definitely not for the squeamish, the book is alive with dark humor and unsettling medical details. In many ways, it’s an oddly fun, albeit gritty glimpse into a world most folks would prefer not to know. After all, no one wants to think paramedics responding to a 9-1-1 call might be stressed out to the point where sanity is a long-lost concept. Worse, that they don’t really care about the patients they’re trying to save.

Talking to film critic Roger Ebert, Martin Scorsese said, “When I read… the book I told (producer) Scott Rudin, who gave me the book, ‘the only man who could write a script of this is Paul Schrader.’”

Hardly strangers, the pair had produced some of the most notable films of the late 20th century. Together the writer and director had crafted Taxi Driver, Raging Bull (1980), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). These films can be dissected in all manner of ways, but more importantly helped define a new kind of cinema thanks to an unflinching display of character flaws. From the dangerous loner to the toxic male to the imperfect savior, every aspect of these movies can be seen filtered into Bringing Out the Dead.

While attempting to stitch together a remake of The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), the pair acrimoniously butted heads once too often. Rather than kill their friendship, however, Schrader advised Scorsese to let the movie die instead.

He said, “Either this film is going to get made and we’re going to become enemies, or this film is not going to get made and we’ll stay friends. So let’s just assume the latter is true and just quit. We’ve done three films, that’s enough.”

This wise decision no doubt gave them the breathing room necessary to make collaboration possible again on Bringing Out the Dead. Scorsese’s Catholic upbringing interestingly pairs well with Schrader’s Calvinist youth. Even when not working together various religious themes pepper their pictures.

Scorsese has always included spiritual symbolism in his films. In Mean Streets (1973), Harvey Keitel often performs actions reminiscent of Catholic sacraments. Despite being a gangster, his character is metaphorically a priest. More obvious visual displays of Catholic sentiments abound in Who’s that Knocking at My Door? (1967). However, over the years, the director learned to tone down and more artistically deliver such notions. Films like Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) play out like sinners in a confessional lamenting their lives. Even The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) is a hubris drive, impenitent confession. And yes, such subtlety went out the window with Silence (2016), yet that movie echoes notions regarding the importance of faith, however that’s defined, seen in Kundun (1998).

Or, as Roger Ebert might put it, those films are “an act of devotion, an act even of spiritual desperation, flung into the eyes of 20th century materialism.”

Paul Schrader excels at writing lonely characters with inaccessible aspects that keep them from connecting to others, and even when the audience can appreciate these self-deluded individuals, few of them are ever on a noble path. Travis Bickle is the easiest example, but more recently is Ethan Hawke’s portrayal of a priest warping into a self-righteous suicide bomber in First Reformed (2017). There’s also a tendency to touch on a kind of “Paradise Lost” by human contact, something perhaps best expressed in The Mosquito Coast (1986) — that unfortunate tendency for human beings to produce their own corruption.

To get the look he desired, director Scorsese brought in cinematographer Robert Richardson. The two had effectively collaborated on Casino. By the time he joined Bringing Out the Dead, thanks to JFK (1991), Richardson had won the first of three Academy Awards he would earn for cinematography, not to mention multiple nominations. His work on films like Platoon (1986), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), and Snow Falling on Cedars (1999) made him an ideal choice. Particularly that last one, since its use of skip-bleaching caught Scorsese’s attention. Bypassing the bleach used in film development results in more “silver on the negative, the added density basically acts like added exposure, and makes the whites much whiter.”

This, along with some dynamic lighting choices, turned Bringing Out the Dead into a truly hallucinatory experience. Light spills in pockets as if splattered across the dark city. When it falls on a person they seem to glow as though shining from within, but shuffling a centimeter or two, they lose that aura very easily. Such visual poetics fill the celluloid canvas of the film.

Meanwhile, ambulance sirens wail like eerie trumpets at a losing battle, often subsiding to allow Scorsese’s effective use of pop music. The city and its inhabitants are in sharp focus as if certainty exists, but quickly smear into blurs racing out of sight. Though most of the film takes place at night, a slate grey tint keeps the daytime world from ever looking rosy or clean. And certainly, one cannot forget the people, not simply the stellar cast, but the nocturnal population of New York. Those pedestrians shambling through their own personal nightmares, sometimes yelling for victims to die; someone else’s suffering their entertainment—grim distraction from existence. Bringing Out the Dead displays a haunting world full of misery where those altruistic enough to assist the wounded are rewarded with soul crushing grief and insanity.

Depicting such an existence required a top-notch cast. Before becoming an over-the-top caricature, Nicolas Cage used to balance his enthusiastic portrayals more wisely (Vampire’s Kiss (1988) notwithstanding). His visually expressive performance here has hints of Silent era acting while his monotone voice-over is a testament to defeat.

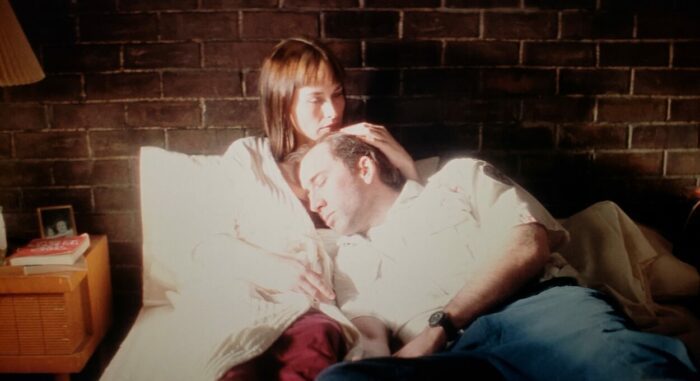

Mary Burke played by Patricia Arquette gives his character a chance to humanize. In the film, her estranged father is one of Frank’s first patients. Arquette is wonderfully withdrawn, portraying someone afraid to hope. They’re both people too aware of life’s thorns to reach out. It’s only when Frank cuts the only tie between them, by euthanizing her brain-dead dad, they finally connect.

As the film unfolds over three nights, Frank is given different partners. There’s John Goodman as Larry, a person so thoroughly devoted to not letting the job affect him that the second it does he calls in sick. He’s then replaced by Ving Rhames, who’s cigar smoking Marcus seems better suited for the pulpit than paramedic predicaments. Finally, there’s Tom Sizemore as Tom Wolls, whom Travis Bickle would advise to chill out. Each has their own mindset on how to survive the job, and though their advice fails to reach Frank, each partner does have concern for his well-being. Goodman professes detachment, Rhames preaches religion, and Sizemore practices what could be called medical cruelty, intended to make patients regret the choices that led to his presence.

Similar attitudes abound throughout Bringing Out the Dead. The Hell’s Kitchen hospital the paramedics routinely return to features Nurse Constance, played by Mary Beth Hurt, whose snarky inquiries ask patients why anyone should help them. The harried doctors and nurses played by the likes of Aida Turturro, Catrina Ganey, and Nestor Serrano are always looking for excuses not to accept patients. Consequently, there’s a shade of Catch-22 to the tale as well.

Cage consistently begs to be fired by a boss who keeps promising it’ll happen tomorrow. Even when the higher ups suggest terminating his employment, the boss won’t be told what to do. Besides, the medical service is short-staffed, or whatever other excuse he can produce to keep putting Frank back in an ambulance.

As such, Bringing Out the Dead is occasionally a darkly hilarious movie. Nothing proves that more than Ving Rhames pretending to resurrect a heroin overdose through the power of prayer, though Narcan is the real hero. Juxtapose that against Tom Sizemore’s character who sarcastically “cures” a man of suicidal ideation by attaching an EKG sticky pad to the fellow’s forehead telling him to leave it in place for 24 hours, claiming it’s a cure-all courtesy of NASA. The paramedics all act like saviors, each in their own twisted ways, but Frank has lost the ability to inhabit that role leading to an existential crisis. He has become woefully aware he isn’t salvation, he’s in need of it, and mistakenly believes that means saving lives.

Consequently, Frank floats through a nihilistic dismantling of his own ego. Once he considered himself god-like, snatching people from the jaws of death. Now unable to save anyone, he reevaluates himself as witness rather than savior. For Frank, the paramedics primary role is the illusion of salvation as he bears witness to death. It’s a bizarrely egotistical embrace of pointlessness wherein he angelically comforts the living by fostering the illusion of hope merely by being present.

The 1990s saw a dramatic rise in ironic content. A certain cynical detachment prevailed thanks to the popularity of entertainment like South Park, grunge, and the films of Quentin Tarantino. Not to mention literary works from Bret Easton Ellis, Mark Layner’s “My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist”, and Chuck Palahniuk’s “Fight Club”. Being cool meant not caring about anything because nothing mattered, sarcasm was the height of cleverness, and the pointlessness of existence precluded sentimentality as irrelevant. In a way, irony protected people from the social sin of seeming naïve and nothing was more naïve than caring about something. Where it was once used to deconstruct and illuminate the dark side of culture, irony had become a tool for nihilistic indoctrination and a means of making idle observers feel cleverer.

As Matt Ashby and Brendan Carrol observed, “Lazy cynicism has replaced thoughtful conviction.”

Into this milieu, Scorsese and Schrader delivered Bring Out the Dead. The film flies in the face of the rising cynicism at the time because it never puts the audience above its characters looking down on the bungled and debauched. It instead invites them into a surreal glimpse of their pain hoping to inspire compassion for a horde of burnt-out human beings. Even in a nightmarish world, kindness is more important than the cool cruelty cynicism permits. An expressionistic plea for compassion, Bringing Out the Dead never asked audiences to ridicule its characters, rather to pity them. The movie is full of broken people making bad choices, and even when their actions are contemptible, none are portrayed as beyond redemption, should they so choose.

With Bringing Out the Dead Scorsese crafted an experience of urban expressionism visually unlike any of his films before or since. Expertly adapted by Paul Schrader, the script shines in the hands of a stellar cast, bleeding out dark humor, and heartbreaking humanity alongside challenging themes of mortality, guilt, and forgiveness. The visual stylizations are haunting, and the pace set by editor Thelma Schoonmaker keeps the film flowing. A box office bomb at the time, the film refused to cynically write-off humanity. That’s why, twenty-five years later, it may be time to resurrect Bringing Out the Dead.