If you’re here, you love films and if you love films, there’s a good chance that love began with a Martin Scorsese picture. I remember starting my film watching career as a teenager and his films, being as audacious and electrifying as they are, perfectly bridged the gap from lighter and more accessible fare into something darker, more adult, and more dangerous. Scorsese’s one of those filmmakers one can’t help but associate with a particular kind of film, but who has actually refused to be pigeonholed as much as any other. He’s unquestionably a great modern example of an auteur, but one who has as varied a catalogue as anyone worthy of the name. In the span of five years he made Goodfellas, Cape Fear, Casino and…The Age of Innocence?

From a lesser director, such a varied catalogue would testify towards a “one for them, one for me” approach, but one never comes away from a Scorsese film without feeling as if he put everything on the line to make it. People love to make him the figurehead of the low vs. high art debate, but he’s a true master of both and as a humble student of world cinema and a stalwart champion of global and independent filmmaking, Scorsese will always remain one of the most necessary and justly revered voices in the landscape of modern cinema.

This may all sound like an odd preamble to an article ranking his work.After all, something has to go at the bottom of that list, right?

I can count the number of filmmakers who made as many films as Scorsese has without making a dud on one…I was going to say hand but…honestly, it’s one finger (Akira Kurosawa). So I wish to make it clear that my respect for Scorsese as a filmmaker and as a champion of the arts is as high as anyone’s. However, I do have my preferences as for every one of his films I think is basically perfect, there’s another imperfect one to show the difference.

For this list I’m sticking to his narrative feature films, so no concert films or documentaries or anything like that. Sorry if you came to this list curious to see where The Last Waltz would land.

27. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

And I’ve lost you.

Didn’t take long did it? I know a decent number of you are going to click away on seeing this pick. A lot of people have this at the very top of their rankings, or at least in the top ten, and if anything shows what a master Scorsese is, it’s that I can still say I get why.

The Wolf of Wall Street is an exceptionally well made film. DiCaprio is DiCaprio-ing left, right and centre, Thelma Schoonmaker deserves some kind of honorary award for strapping this mess together and yes, Margot Robbie is very attractive.

But I am part of the community that thinks The Wolf of Wall Street fails to effectively satirize the world it depicts, because of a phenomenon known as the satire paradox, of which I don’t think you’ll find a better example. By laughing at Belfort and men like him, we are indulging them. Look at these horrible men, the film says. Look how funny they are, look how entertaining they are, look how outrageous and sexy and glamorous this all is! He may be trying to give Belfort enough rope to hang himself, but ultimately The Wolf of Wall Street is a deeply unsatisfying and wearying experience, showcasing a truly obnoxious central performance and failing to really contribute any insights beyond: wow, aren’t Wall Street financiers absolute scum?

At three hours, I’m sorry, this film is definitely revelling in the excess it depicts. That’s why people like it. That’s why I don’t. The fact people find this enjoyable to watch proves its abject failure.

26. Boxcar Bertha (1972)

What’s there really to say about Boxcar Bertha? It’s really nothing special. I’d like to say it’s a forgotten, underappreciated gem, but really no one would be watching this if it weren’t on Scorsese completionists’ radars by default. It has somewhat memorable opening and closing sequences that remind you who’s in the director’s chair and Barbara Hershey’s always worth a watch, but beyond that, this is a fairly unremarkable and very typical example of early ’70s exploitation filmmaking. It’s not not worth a watch, as little as I remember it I don’t dislike it, but there’s a reason it hasn’t had a big reassessment.

25. New York Stories (1989)

A hard one to place, Martin Scorsese directed the first section of this anthology film, a triptych of films set in New York, directed by noted local luminaries and based off Scorsese’s contribution itself, I’d actually put this a little higher. It’s certainly an extremely New York story, set in the city’s modern art world, following a middle aged painter (Nick Nolte) who is rejected by his younger girlfriend (Rosanna Arquette) after she realises how little he has to offer her. He ineffectually tries to win her back before rebounding into the arms of another woman he can dazzle for a while with his celebrity until she realises what a bum he is. It’s a pretty en pointe character portrait of a particular kind of narcissistic man who can’t cope with being seen for who he is, and so attaches himself to immature women who leave him as soon as they smarten up. It’s worth a watch honestly, but you can switch off after that, Sofia Coppola and Woody Allen’s shorts are both pretty unwatchable.

24. New York, New York (1977)

Sticking with the New York theme we have New York, New York, Martin Scorsese’s slow and rather tiresome attempt to be Bob Fosse and make another A Star is Born story, following egotistical, motor-mouthed Jazz conductor and an ingenue singer as they each try and make it big. It features perhaps the first truly awful De Niro performance and though the production values are striking the story is tiresome, there’s no chemistry and it drags like nobody’s business. At least you have Liza Minelli doing Liza Minelli things, so it’s not a total loss.

23. The Color of Money (1986)

Yes this film. It’s…fine. I think. It could be bad. There’s some novelty to seeing Scorsese, Paul Newman and Tom Cruise all like up, but I wish they had something more interesting to do than play pool. Honestly I think the three of them actually just meeting up and playing pool together would be more interesting to watch than this legacy sequel to The Hustler (1961) wherein Newman takes cocky young gun Cruise under his wing. There’s some snappy moments of style but this is only a step above Boxcar Bertha. Watch it once you’ve seen everything above it, if then.

22. The Aviator (2004)

Maybe I just don’t like Leonardo DiCaprio’s acting. True, I don’t think I’ve ever truly, truly loved a film he’s been in, except for maybe Django Unchained and that’s a rare supporting role. Anyway, this Hollywood biopic hardly lacks for style, the cinematography and editing are dazzling…the CGI less so, and this does have the completely fair disadvantage of being the kind of movie I’ve grown so sick of lately: obligatory Hollywood biopics of famous people. Howard Hughes was an interesting guy, he lived quite a life so let’s put it on film, why not?

Also why?

The Aviator just doesn’t get to the heart of anything. It looks the part and talks a big game but there’s not much substance here to get caught up on. It feels as if someone thought that just by recounting the events of his life that some sort of deeper meaning would naturally emerge, but as with The Wolf of Wall Street, shallow, egotistical rich people make poor subjects and you end up with a very drawn out film that still feels like it ends just as it was getting started.

21. Hugo (2011)

Very much a film of two halves, if New York, New York was Scorsese trying to be Bob Fosse, then Hugo is him trying to be Spielberg, telling a schmaltzy family adventure that swiftly and thankfully gets abandoned in favour of a sincere and heartfelt paean to the early days of silent film, when the medium itself was born out of adept stagecraft and fragile celluloid. The second half, a fictionalized retelling of the life of George Méliès is frankly delightful. The first half, about a little orphaned boy living in a station, attempting to fix a creepy mechanical doll while being chased by Sacha Baron Cohen doing a funny walk, is pretty poor fare.

20. After Hours (1985)

There comes a point at which an “underrated” film gets called underrated so often that it ceases to be underrated and in fact becomes overrated. I call this “The Prestige syndrome” and After Hours suffers from it greatly. Yes, there are some terrific moments in the tale of Griffin Dunne’s everyman office worker who after a series of unfortunate events finds himself lost in the big city, the “Is That All There Is?” scene and the film’s brilliantly surreal ending are justly praised, and the film does build to a great climax. However, a decent proportion of the movie is just kind of dull and not very funny. It’s a little random and directionless and has never made the impact on me that it clearly has on others. It’s a cute little movie, but nothing more.

19. Shutter Island (2010)

An extremely well produced mid budget thriller, Shutter Island holds the distinction of being the first Scorsese film released while I was old enough to see it in theatres and I remember the experience vividly. The film’s cinematography is fantastic and the Dachau sequence is spellbindingly horrible, but the twist ending, once you know it, is the kind of anti-climax that cheapens the experience in retrospect and leaves one with little desire to revisit it. It elevates the movie to a plateau where its forced to compete with movies like Fight Club or The Ninth Configuration that it just can’t hold its flickering match up to.

18. The Departed (2006)

Okay, now we’re starting to get good. I like The Departed, but I don’t love it. It’s a very watchable and consistently engaging crime drama, stylishly directed, as ever, and featuring some career highs from stars DiCaprio and Damon, plus some truly unhinged supporting performances from Mark Wahlberg and Jack Nicholson. It isn’t anything too special, just a very solid, decently plotted remake that does what a good American remake of an International feature should: change the context and rewrite the story from there, up the budget, up the ante with some major shocks, and that’s about all you need.

Can’t not mention the rat though. To quote Ralph Wiggum, “the rat symbolizes obviousness”.

17. The King of Comedy (1983)

Another victim of “The Prestige syndrome” I fear, would you all hate me if I said I prefer Joker?

By a lot…

Yes, there are respects in which this film has aged extremely well in its satire of fame, obsession and the absurdity of celebrity culture. But it’s also aged quite poorly as well, because the conversation has fairly passed it by, and even by the standards of the time, does it hit with the ferocity and merciless intellect of a film like Network?

There’s some fun to be had in seeing Jerry Lewis play against type and Sandra Bernhard is a hoot, but aside from a few specific moments where the film really hits its mark, it’s mostly a slower, less purposeful version of something we’ve seen a million times before and since.

16. Kundun (1997)

A real oddity in Scorsese’s canon, Kundun is an imperfect blend of spiritualist Scorsese and historical epic Scorsese. There’s a lot of respects in which I think his biopic of the Dalai Lama comes off pretty well, even moments where it feels like a diminished companion piece to Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (best film ever to win the Best Picture Oscar by the way). It’s one of the stranger and less confident films in Scorsese’s oeuvre, it feels odd that it came out right when he was making some of his most definitive works. Some of these creative decisions really pay off, the Philip Glass score for one, and it kind of makes you wish there were more bold choices like that. It feels rather rushed at times, while also being rather slow paced, but there’s no denying the evident sincerity with which it’s made, even if it is the weakest of Scorsese’s faith-based films.

15. Who’s That Knocking at My Door (1967)

Martin Scorsese’s first ever feature film and damn did he hit the ground running! It’s rough around the edges to be sure but that’s what I love about it, it’s so raw and vital, the closest Scorsese ever got to New Wave. There’s so much youthful and kinetic energy behind it, it’s the kind of film he could never make today. It might have placed even higher on this list if not for the fact it suffers from direct comparison to another much better film he made shortly afterwards and for which this tale of mean-street kid Harvey Keitel torn between his catholic guilt and the love of a good woman mostly functions as a dry run.

14. The Irishman (2019)

A central pillar of that cycle I mentioned about Scorsese’s history of America as the history of amoral screwups, The Irishman again follows a man so destroyed by war that he has lost any kind of moral compass, it’s at this point in the list where the films start getting really good. The Irishman is very much an old man’s film. It’s stuck in the past, often in the best ways, with its maturity and muted pace a marked difference from the hyper-intense style for which The Wolf of Wall Street may have been a last hurrah. Its first half feels like a fond reunion tour for Scorsese and his pals. The film’s third act is where Scorsese finally alights on new ground, that of old age and regret, with a truly existential sense of isolation closing in on Sheeran as his violent life drives away or outlasts anyone who ever cared for him. Too emotionally stunted to truly repent or acknowledge his appalling crimes, he is left in frustrated solitude, stonewalled against human contact by his own stubbornness and lack of empathy. For the first time Scorsese truly seems to see the monstrousness in his gangster characters, and in so doing, makes them seem all the more human.

13. The Age of Innocence (1993)

As stereotypically stuffy as any costume drama, The Age of Innocence is perhaps more of an outlier in Scorsese’s canon than any other of his films, but not in terms of quality. Films like Mean Streets and the aforementioned Who’s That Knocking at My Door touch on characters torn between social pressure and their hearts, as does Killers of the Flower Moon in a less convincing way, but The Age of Innocence is the most focused example of this theme, an explicit tale of the tragedy of the social constructions binding us, inextricable from our feelings. It’s a tender and sensitive drama and a necessary reminder of Scorsese’s ability to express these modes, something he does with unusual grace, albeit too rarely.

12. Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Amid the overwhelming praise that is of course the natural response to a film like Killers of the Flower Moon, there’s also been a distinct and growing backlash to the film. These naysayers can be divided into two distinct groups: those who feel that Scorsese’s outsiders perspective is still an imperfect vehicle for a story about the violence inflicted upon Native Americans and that although he still got a lot right, he and his white writers still approach the story from a white perspective and that Killers of the Flower Moon is still at the end of the day yet another example of white artists as the architects of Native Americans’ history, and then there’s the other group who are just bitching about it being too long.

I’m a little of two minds on the matter (the representation debate that is) not the length issue. For one, yes, I wish Molly had been the protagonist instead of giving us yet another odious white guy role for DiCaprio to overact his way through, but I only think that because what we do get from her and the other Osage characters says so much. Gladstone is a powerhouse and she carries Killers of the Flower Moon, despite her supporting role. We needed much more of her, but what we do get is enough to land it at number twelve on this list. And that final scene…man, what a knockout.

11. Gangs of New York (2002)

The best of Scorsese’s collaborations with regular lead Leonardo DiCaprio and it doesn’t even break the top ten. There’s nothing wrong with DiCaprio’s performance though, far from it. Nor even really Cameron Diaz’s. They’re just…outclassed, shall we say?

At heart, Gangs of New York is a fairly uninspired revenge story, following Amsterdam Vallon (DiCaprio) as he inveigles his way into the inner circle of the crime boss who killed his father (Daniel Day Lewis). Sure the film’s cynical perspective on fatherhood, American history and immigration gives it a little meat to chew on but it’s hardly the most profound or rigorous piece of iconoclasm. Thankfully that generic macho melodrama is an opportunity for Scorsese to paint on the biggest canvas of his career, and for Day Lewis, along with the rest of the film’s enviable line-up of acting luminaries, to chew the scenery for all their worth. The setting is unique and stunningly baroque, the opening action scene is a masterpiece unto itself and the top-hatted, resplendently moustachioed Day Lewis is cock of the walk giving what might be the most purely entertaining performance of Scorsese’s whole oeuvre. It’s the most gorgeously decadent thing Scorsese’s made outside of The Wolf of Wall Street and just has so much more going on story-wise to match the sense of scale it has.

10. Raging Bull (1980)

Raging Bull may be the most brutal watch on this list. I had a hard time placing it as although I may prefer some films beneath it on this list, but I have a harder time arguing against it. If there’s any film here I’ll concede to maybe placing too low, it’s this one. It’s pretty inarguable that this is one of the greatest triumphs of Scorsese’s career and one of its most defining moments, but there’s also not much he’s done that’s like it. It fits the mould of a conventional biopic, but with so much of what beguiles and satisfies about the genre is gone. It may be the darkest film Scorsese’s made. An odyssey of pain where the finessed style with which it’s told heightens and deepens the tragedy rather than glamorises it.

It may be the crowning glory of Scorsese’s craft, and that of its star Robert De Niro who gives his best performance as washed-up boxer Jake La Motta, a man who spent his life brutalizing himself and others for the audience’s pleasure and adulation. And as with so many of Scorsese’s protagonists, there’s no redemption or reward waiting for him to reassure him it was actually all worth it somehow. It may be the definitive film about toxic masculinity in its raw, modern form.

9. Casino (1995)

Discount Goodfellas is still so damn watchable it lands pretty high on any list. There was a time when I preferred it just cause it’s more fun to watch than the earlier movie. It’s the first time Scorsese made an arguably redundant film, but I think it’s still aged pretty damn well. The story of the rise and fall of the Golden Age of mob-owned casinos in Las Vegas as told by a two-bit bookmaker who was handed the keys to the kingdom just because he’d do as he’s told, Casino is a wry, indulgent and humorous movie that would be wearying if it weren’t so much fun to watch. It sets up a lot of the themes Scorsese has begun to return to in recent years, but it’s clear he’s not yet taking his subjects as seriously at this point. He’s playing it pretty straight-faced but there’s an undeniably farcical quality to the storytelling this time, making it clear that these guys just really aren’t terribly bright. There’s no sense that we’re being legitimately beguiled by the high-life they’re living. De Niro dresses in his expensive silks and oversized sunglasses and he doesn’t look cool, he looks absolutely ridiculous. It may be an attempt to remake his greatest hit, but it still hits all the right notes.

8. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Of all the top-tier Scorsese films, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore feels the least like a Scorsese film of them all. It fits in more with the contemporary wave of New Hollywood filmmaking that Scorsese was first a part of, and yes, it remains to this day the last Scorsese film to have a woman protagonist. And yes, I won’t pretend that doesn’t make it feel like a breath of fresh air. There’s no mobsters or guns or violence, just the story of a single mother trying to make a home for herself and her son after her abusive husband dies. The titular Alice (Ellen Burstyn) moves away, tries to get a job as a singer again, winds up waiting tables in a fast-paced diner and eventually falls for a handsome customer (Kris Kristofferson). And that’s kind of awesome. It really is a refreshingly sincere and relatable film, both as a Scorsese film and just for its time period, Alice is the most down to earth protagonist any Scorsese film has ever had, and her interactions with her new co-workers, her son, and her new boyfriend are just incredibly credible, endearing and wholesome. The opening scene is an extraordinary old Hollywood pastiche, but from then on Scorsese takes a back seat and lets the incredibly well observed writing and naturalistic performances take over, and the result is one of the most convincing and three dimensional films he’s ever made.

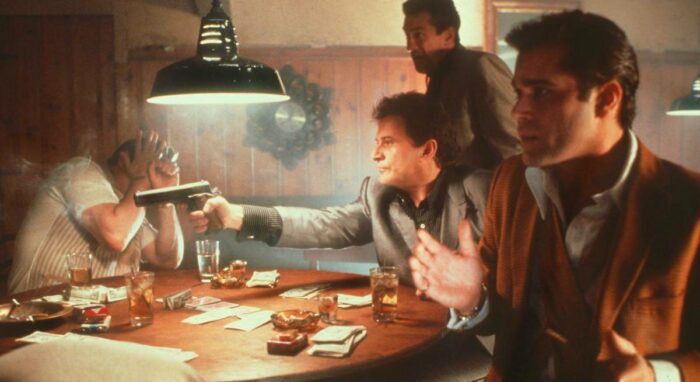

7. Goodfellas (1990)

We’re running out of films to put at number one aren’t we?

I love Goodfellas, does it need saying? One of the best gangster films ever made, Scorsese becomes the perfect shepherd through a flock of wolves as brash schoolkid Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) finds himself recruited into the criminal fraternity up the street, seduced by a life of backroom privileges, communal bonding and easy money, until the bodies start to pile up. It’s a crying shame Scorsese never got to work with Liotta and Lorraine Bracco again cause they’re such perfect muses for the style he’s pioneering here. It’s a more concise and focused film than Casino, with slightly more relatable and likable characters, and the conspiratorial tone of Nicholas Pileggi’s screenplay crackles with an energy that only ’90s Scorsese could’ve matched.

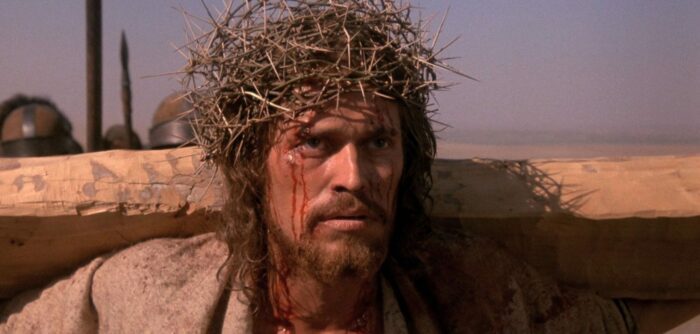

6. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

One of the more divisive films in Scorsese’s canon, The Last Temptation of Christ was controversial upon its release. Many were confused or enraged by its blasphemous portrayal of Jesus as an all too human and conflicted individual, a human prophet as confused and frustrated by the opacity of God’s intent as any of us. This is the most relatable version of Christ ever put to film, a vessel of God’s divine grace, yet unsure of his mission and plagued by doubt and human feeling. The film’s audacious third act presents the titular final test, where Christ is offered the chance to renounce his role as prophet and become human, a choice he almost takes, until confronted with the depth of his responsibility, leading to one of the most astonishing endings to any work of cinema, as its hero expires, the film itself (supposedly unintentionally) disintegrates and Peter Gabriel’s score swells to an almost unbearable intensity.

It’s an astoundingly layered, nuanced and intelligent insight into not just the nature of faith but its purpose and practicality, and it well be the most human work Scorsese’s ever made, as his fervor and human frailty bleed into its every moment.

5. Cape Fear (1991)

Cape Fear may be the best of Scorsese’s commercial, mainstream works. A remake of a celebrated classic (a weak and uninteresting film which Scorsese’s version leaves utterly in its dust as far as I’m concerned), starring big names giving bigger performances, Cape Fear subtly inverts a few specific elements of the original, turning a generic “good man faced with evil” movie into a horrifying confrontation with potential flaws in the justice system, where someone can exploit misogyny and shame and get away with it, unless our antihero breaks the law. In the original, Sam Bowden was just the prosecutor who put unrepentant rapist Max Cady away, but in this version, family man Bowden (Nick Nolte) was supposed to be defending Cady (Robert De Niro), but knowingly failed to defend him because he knew how dangerous he was. Cady was denied his rights and he wants vengeance.

The film also ages up Bowden’s daughter Danielle (a career-best Juliette Lewis), an innocent fourteen in the original, a curious and naive fifteen, just old enough to have some agency. Cady doesn’t stalk her in this version, he seduces her, something far more insidious, realistic and uncomfortable. The film moves like a freight-train for its first hour or so, until it slows down dramatically in the skin crawling scene where the sleazy Cady puts the moves on Danielle and she falls for his charms. From there the film devolves down a darker path, escalating the violence and intensity until its full-throttle climax that feels like a true descent into the maelstrom of hell.

The only thing that might hold this back from its claim as one of the best legal thrillers ever made is De Niro’s performance, which, let’s be honest, is completely demented and will always remain divisive with his hilariously fruity southern accent. For my part, I love seeing De Niro show this much fire. It’s up there with Raging Bull and Heat as one of his best performances in my eyes. He holds nothing back and feels genuinely demonic at times, and Nolte, Lewis and Jessica Lange are fantastic too.

4. Silence (2016)

Silence’s slowness may hold it back from a top three spot, but my goodness, what a marvel of a film! This one’s also a remake, of the 1971 film by Masahiro Shinoda, and once again I think Scorsese outdid the original at every turn, escalating everything to a brutal and devastating level. The film follows the inquisition of Christians by the Japanese authorities, as a Spanish missionary (Andrew Garfield) searches for his mentor in the foreign land, is captured, and coerced into apostatizing. The martyrs’ tale holds evident similarities to The Last Temptation of Christ, but this film’s drama is all the more agonizing for being so real, and so foolish. It’s a true test of how far one is willing to go to guard their spirit against authoritarian brutality, as Rodriguez (Garfield) teaches non-violence and love, while the authorities respond only with more death, making brutal examples of those who oppose them. Rodriguez’s intractability is frustratingly tragic, as the suffering he witnesses weakens his resolve. What good are his principles when sticking to them has such manifest and immediate negative consequences to others?

Silence is a true testament to Scorsese’s mastery of his craft, his best film in more than twenty years, and a devastatingly bittersweet paean to the quiet resolve of those who hold onto their convictions, come what may. And in its subtle, transcendent beauty, the ending of Silence is every bit as stirring and unforgettable as that of The Last Temptation of Christ.

3. Mean Streets (1973)

The true making of Scorsese as an auteur, Mean Streets is everything fantastic about Who’s That Knocking at My Door and Goodfellas combined. It has the personal, raw, guerrilla intensity and exuberance of the former, and the audacious flair and finesse of the latter. It also remains one of the most personal of Scorsese’s films, with the director himself and not star Harvey Keitel delivering protagonist Charlie’s interior monologue voice-over. From the needle-drops to the camerawork to the editing, everything about Mean Streets remains cutting edge, exhilarating and captivating to this day.

Charlie is another antihero who finds himself torn between love and social expectations. His mid-tier mobster uncle expects great things of him, but both his romance with epileptic Teresa (Amy Robinson) and his association with live-wire best friend Johnny Boy (De Niro at his most magnetic) are reflecting badly on him and drawing him into danger. Combining humor, violence, religion and tragedy as only Scorsese can, Mean Streets thrums with the youthful energy of a great artist hot from the forge.

2. Taxi Driver (1976)

Perhaps the defining film of not only Scorsese’s career, but of its star and writer as well, Taxi Driver is the most direct of Scorsese’s character studies of broken, unhappy, morally vacuous men. Following an alienated, jaded and mentally unstable veteran as he drifts through a society he is unable to meaningfully connect with as he searches for purpose, but the only thing that gives him a sense of power is violence, and so it is with violence that he resolves to find something to give his life meaning.

Taxi Driver is so familiar, so entrenched in the fabric of society and pop culture, that it’s easy to forget what a magnetic film it is to watch. It has such a sulky, acrid tone, it sticks in the back of your throat, with that incredible score that veers from the faux-serene to the hellishly intense over and over. It’s truly unhinged and dangerous in all the best ways, encouraging us to sympathize and identify with a well-intended but emotionally stunted man and his misanthropic desire to be acknowledged by a world whose loathing he wholly reciprocates and with which he is incapable of communicating effectively. It’s so articulate in its tragic nihilism, there’s no wonder no other movie can touch this theme without being at least compared to it, if not returning to this well directly for influence (once again, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, Joker is amazing for all the same reasons).

What could possibly be better?

1. Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

From the first juddering chords of Van Morrison’s “TB Sheets” to the hauntingly beautiful final scene, Bringing Out the Dead is demented, horrifying, heartbreaking, hilarious and completely and utterly electrifying. In such a celebrated filmography, I can’t understand how this has gone by the wayside when it embodies absolutely everything a Scorsese film is or could be. Far from a messy minor work in an eclectic catalog, as which it is often dismissed, Bringing Out the Dead is in fact the culmination and coalescing of more than three decades of formal and thematic growth and experimentation, the most complete and all encompassing work of Scorsese’s whole career.

Following New York Paramedic Frank Pierce (still to this day, the best use of Nicholas Cage ever) as insomnia, the stress of his job, and a series of increasingly unstable partners erode his mind over the course of three long night shifts, Bringing Out the Dead is the meeting point between the last three films on this list. It’s a backhanded hate letter to the vibrant, sprawling urban hell-scape that is New York City, it’s a portrait of an unraveling man always on the move in search of redemption, and it’s as intensely spiritual a film as any Scorsese has ever made. It’s playing the same themes as those movies but rearranged into a different key and at a faster tempo, whip-panning wildly from the sublime to the ridiculous with a mesmerizing sense of wit, sadness and humanity. Bringing Out the Dead is what you get when you put a truly good person in Travis Bickle’s position. Left to tend to the sick and dying at the bottom rung of a society tearing itself apart, Frank earnestly loves and cares for those he meets, but he’s running on fumes and no longer knows whether to laugh or cry as he ushers them through the hospital doors.

And it’s just such a stunning cinematic experience. A cathartic fever dream traversing the highest highs and the lowest lows of the human condition, a bolder, braver and more audacious work of cinema than most directors would make in a hundred lifetimes. I cannot sing its praises enough. It’s one of my favorite movies and played a significant role in securing my lifelong love of cinema.