Jason Reitman’s first feature film, Thank You for Smoking, is shocking in its moral ambivalence. The story—adapted from a novel of the same name by Christopher Buckley—takes the audience on a tour of authority figures and role models, from politicians to Hollywood executives, but there are no heroes to be found among them. It could be criticised for its whitewashed discussions of fraught political issues (and perhaps it should be) but then, providing a moral guidebook is not the point of the movie. Instead we are invited to dive head-first into the absurd and misanthropic modern world, where there is only one guiding principle: question everything.

It’s kinda like being a movie star—it’s what I do, I talk for a living

– Nick Naylor

Aaron Eckhart is brilliant as the reprehensible protagonist, Nick Naylor, a lobbyist for the tobacco industry, and a master of spin. He’s a real American man (gratuitous baseball shot included) with an ego that could cover the contiguous states twice over. He is handsome, charming, and unyielding—the kind of person we would expect to be a hero, and yet he is described by people as “a mass-murderer, bloodsucker, pimp, profiteer, child-killer, and […] yuppie Mephistopheles”. Why should Naylor choose a career as deplorable as defending cigarettes? Because he’s “good at it”, and apparently the moral issue just doesn’t bother him. At one point he watches a movie scene where a soldier dies holding a pack of cigarettes and for a moment his face seems to promise a sympathetic epiphany—instead, he is hit with a new idea about how to sell more cigarettes.

If you can do Tobacco, you can do anything

– Nick Naylor

For a movie that is so much about cigarettes, it’s not really about cigarettes at all. In fact, neither Naylor, nor any of the other characters, smokes a cigarette over the course of the film. His story is about ambition, it’s about proving himself to his son, and it’s about petty revenge. As much as we might not want to admit it, a character who acts on petty and selfish human instincts is more relatable than one who is purely an ideologue—the popularity of anti-heroes, such as Marvel’s Loki, can attest to this. The rather bleak upshot of this is that the viewer may be comforted to know that they don’t need to be a good person in order to be the main character.

Everyone’s got a mortgage to pay. The yuppie Nuremberg defence

– Nick Naylor

At the film’s climax, Naylor gives a speech about the responsibilities of parenthood. The biggest test of his character is his relationship with his son, Joey, and it is full of contradictions. Subtle though it may be, it is perhaps the most heartwarming moment of the film (not that there are many to choose from) when Naylor, on a trip to California, abandons crisp corporate Hollywood and the recommendation of a restaurant that only sells white food to eat hot dogs on an amusement pier with Joey. However, his responsibility to be a good father conflicts with his career, and arguably at the end of the movie, his stubborn self-righteousness trumps this responsibility: “if he really wants a cigarette, I’ll buy him his first pack”.

I actually meant what I said about responsibility. Some things are just more important than paying a mortgage

– Nick Naylor

Over the course of the movie, Joey (Cameron Bright) will go from being ashamed of his father to deifying him. Joey is intelligent, a little precocious, and quickly learns his father’s powers of manipulation, using them to convince his mother to let him go to California. It is argued by a journalist that he is being “groomed for the job”, and this may indeed be true, even if it’s unintentional. Naylor explains his job to Joey using an ice cream analogy, in which Joey must argue for chocolate being the best, and Naylor must argue for vanilla. Now of course neither can be ‘right’, but “if it’s your job to be right,” Naylor says, “then you’re never wrong”. Later, they both enjoy vanilla cones on the Ferris wheel, symbolising that Joey has been won over. Moreover, at the end of the movie, Joey wins a debating competition, apparently delighted that he has inherited his father’s talent. Given the trouble it has caused his father (and the world) it’s difficult to know whether to be touched or horrified by this.

Who cares what the Brads of the world think? He’s not my Dad

– Joey Naylor

The theme of fathers and sons continues in the character of The Captain (Robert Duvall). This aspect of the movie bites at the idolisation of older generations. Problematically, there are no African-American characters in the principal cast, however the wait-staff at The Captain’s club is entirely composed of Black men; this is uncomfortably reminiscent of the Old American world that The Captain is fabricating for himself. This was a world that was romanticised after the Second World War, and characterised by people like John D. Rockefeller, who was on the one hand an American ‘hero’, and on the other, responsible for the lucrative but morally bankrupt oil industry.

For The Captain, it’s not oil, it’s cigarettes—the dangers of idealisation remain. The Captain calls Naylor “son” and tells him that “tobacco takes care of its own”, playing on the assumed virtue of the nuclear family; he also compares the war on tobacco to actual war, going so far as to quote Churchill, misappropriating actual heroism. With his Old American attitude comes the implicit desire to restore the tobacco industry (or America, or the world) to a former ‘glory’ that is defined by privilege and apathy. But just as The Captain is convinced that his way of doing things is the right way of doing things—down to the correct way to prepare a mojito—Nick Naylor is too. And arguably, from an outsider’s perspective, The Captain is a bad influence on Naylor, the same way Naylor is a bad influence on Joey. This movie makes characters look foolish for making heroes out of their fathers.

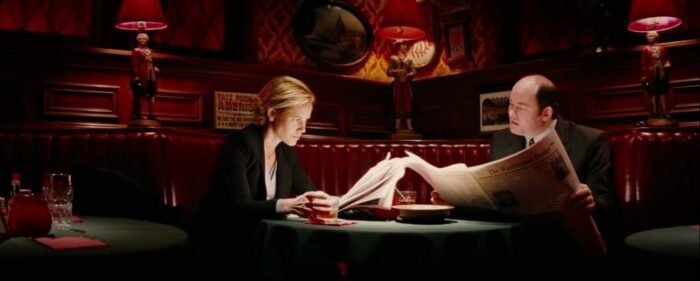

Naylor’s only friends are Polly Bailey (Maria Bello) and Bobby Jay Bliss (David Koechner), his fellow “Merchants of Death”—together, they are the M.O.D. Squad. They frequently compete over whose job kills more people, and Naylor, holding the record, brags that “no terrorist would bother with either of (them)”. Their friendship is an entertaining cycle of bad influence. However, to a viewer in 2021, the M.O.D. Squad scenes are jarring in a more unpleasant way, as the cracks about gun violence certainly have not aged well. It is an unfortunate reminder of how dangerous the flippant attitude they encourage in each other is. And in light of this, it is all the more meaningful when their philosophy is summed up in a slice of apple pie topped with cheese: “that’s disgusting” “it’s American”.

Now he looks like a victim, lucky bastard

– Senator Finistirre

While you might expect this discreditable behaviour from the Merchants of Death, Thank You for Smoking goes so far as to put the ‘honourable’ members of society under the same cynical glare—starting with a politician. Senator Finistirre (William H Macy) is completely unsympathetic, using “cancer kid” as a means to an end. He calls himself “a Senator who is supposed to be tough on tobacco”, implying that his attitude towards Naylor is more about his image as a politician than any real ethical concerns. Here the film is at its most cynical, implying that everyone has a selfish reason for doing good things. Are we, the audience (or even the voters) the foolish ones, for expecting anything better?

While it’s at it, the movie takes a quick jab at PC culture, when the idiotic Senator proposes digitally rendering cigarettes out of old movies and calls it “improving history”. But the persistent message of the film is that we can’t actually improve anything, because no one will ever decide who is right; all we can do is cover history with pretty words, or digitally rendered party horns.

Perhaps as much of a hypocrite as the Senator is Lorne Lutch (Sam Elliott). Lutch, in this universe, was the original Marlboro Man, and is now dying of lung cancer, endeavouring to take the tobacco industry with him when he goes. Naylor presents him with a dilemma that could be straight out of an ethics textbook: either stop causing trouble for the cigarette companies and take The Captain’s bribe money to spend on his family, or stick to his principles and expose The Captain, but turn the money down. As Naylor, ever the pessimist about human nature, predicts, he takes the money. But wouldn’t you?

Being a lobbyist or a politician is like being a storyteller of sorts, but next the movie comes for storytellers in a more literal sense. Hollywood executive Jeff Megall (Rob Lowe) is presented as avaricious and apathetic—his company is even called E.G.O. (Entertainment Global Offices). The California montage results in one of the best self-deprecating gags of the movie—a homeless man holding a cardboard sign that reads ‘screenplay for sale’; apparently, filmmakers must either be struggling artists, or heartless corporate sellouts.

In a similar way, journalism is lampooned through the manipulative and arrogant Heather Holloway (Katie Holmes). Despite her initial role as a promising love-interest, Holloway turns out to be just as much a hypocrite as the rest, and Naylor is conceited enough to believe she genuinely liked him, despite his friends’ warnings. Her defence for betrayal is no better than his: “we both love our jobs”. Filmmaking and journalism are both aspirational professions (in fact, many of Joey’s classmates said they wanted to be movie stars) but this movie is merciless in its rampage against everyone who uses words to make their living.

It’s not my role to decide for them—it’d be morally presumptuous

– Jeff Megall

The final sequence of the movie sees Nick Naylor continuing to use his powers of spin for morally ambiguous ends, this time teaching cellphone marketers how to strategically dismiss accusations that they cause brain cancer—all while comparing himself to Charles Manson in the voice-over narration. What really sets this movie apart is the lack of moral development or redemption. The typical arc would be that by the end of the movie, Naylor realises the truly ignoble nature of his profession, and leaves it behind to become an upstanding and honourable father figure. Indeed, there is an alternate ending to this movie where just that happens—it was pushed for by the studio, but ultimately abandoned. Nothing about the film’s biting cynicism warrants a saccharine ending. In fact, it would lose some of its integrity by suggesting that the hypocritical world it has so painstakingly illustrated could facilitate redemption. ‘Justice’ in this world is primarily about narrative irony, since the closest we come to it is Naylor’s near-death by forced nicotine consumption.

Although, if spun correctly, it can be argued that Naylor is a virtuous character. For example, The Captain praises his loyalty. He also has an incongruous moment of humility when he lets his boss take the credit for his movie idea. Loyalty and humility are both virtues, after all. However, this probably says more about how we define and employ the word ‘virtue’ than it does about Naylor. Inevitably, the audience is tricked into rooting for Nick Naylor, but only for as long as they are watching the movie.

The genre of dark comedy is an interesting one—is it meant to inspire misanthropy? Altruism? Is it satisfying if it only makes you laugh? We shouldn’t expect filmmakers or other artists to provide us with a coherent system of ethics—maybe the point is that we shouldn’t expect that of anybody.

On the other hand, in what might just be a throw-away quip, the M.O.D. Squad draws the line of “moral flexibility” at baby seal poaching. If poaching baby seals is the wrong thing to do, there must be a right thing to do as well, even if the characters generally choose to ignore this fact for their own convenience.

There are no heroes in Thank You for Smoking, but don’t let their apathy for goodness fool you into thinking it doesn’t exist.