For a war movie, Dogfight seems appropriately named, doesn’t it? With this month’s focus on war films as a genre, a film titled Dogfight would seem to fit right in with a Wings or a Top Gun. A dogfight, of course, implies a melee, a fierce battle between combatants in flight, a term that was first coined at the end of World War I and entered the general lexicon in World War II, describing tactical, attacking, and evasive engagements. But Dogfight—directed by Nancy Savoca from a Bob Comfort script in 1991 and starring River Phoenix and Lili Taylor—isn’t “that kind” of war movie, and indeed, its titular dogfight isn’t “that kind” of dogfight.

Unlike so many war films that focus on accomplishment of an objective and reveres intra-group camaraderie, Dogfight tells a different kind of war story, one with nearly no combat at all. Rather, Savoca’s delightful coming-of-age film takes the perspective of a memorable young San Francisco folkie (Taylor) whose first romantic encounter occurs the last stateside evening of a Marine recruit’s (Phoenix) impending deployment to Vietnam. A near-forgotten gem, Dogfight elicits moving performances in a tender coming-of-age wartime romance that posits a memorable critique of military misogyny and machismo.

The script for Dogfight, written by ex-Marine Comfort and largely from his own experience, was brought to Savoca and her husband producer Rich Guay by Phoenix. (Her and Guay’s telling DVD commentary track provides the preproduction insights here.) Savoca felt that the script’s jocular mood and casual misogyny gave Phoenix’s Eddie Birdlace a clear narrative arc. But Taylor’s Rose Feeney was underwritten. So Savoca met with the two prior to rehearsals and gave both actors room to inhabit their characters, and the result was a spirit of improvisation and an aura of trust between the three.

Meanwhile, Guay hired Dale Dye—by then Hollywood’s most frequently hired military adviser who had served as a Marine for two tours in Vietnam, receiving a Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts for his wounds suffered in combat—to lead Phoenix and his male co-star buddies through a military boot camp prior to the shoot. Dye also lent his experience to what must be the briefest moment of combat ever shot for a film, though it’s clear early on that this Dogfight will be about something other than combat.

Dye’s training instilled in Phoenix and others the requisite posture and machismo for their roles as the four “B-Boys” who develop a bond from their last-name assignment together. In his too-short life, Phoenix left behind just a dozen or so films, and his other, better-known 1991 film, My Own Private Idaho, featured him a narcoleptic, addicted hustler, all ambling and strung-out, a role nearly opposite to his Eddie Birdlace here. His Birdlace in Dogfight is twenty times straighter-laced, but it’s clear he’s putting on an air of false machismo to fulfill others’ expectations.

Dogfight is set on the eve of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. On their last night stateside before their deployment to Vietnam, Birdlace and his B-Boy buddies plan a “dogfight.” Each Marine kicks in $50 to the kitty, and the winner takes all. The contest? To bring to the party the biggest “dog”—that is to say, the ugliest date. The gig is almost impossibly cruel, but one grounded in Comfort’s Marine experience and the toxic misogyny of military inculcation.

Savoca handles this egregiously mean-spirited ruse with grace. She allows her audience to clue in on the joke slowly and even enjoy a modest laugh or two at some of the girls’ expense. But when Eddie tags Rose, a quiet teen toiling in her mom’s café, the film’s point-of-view subtly shifts. Rose sees through Eddie’s puerile come-ons but accepts his invitation. When she learns of the set-up—that she and the other invitees are the “dogs” subject to the Marines’ scorn—her anguish is palpable and anger understandable. It’s a delicate balancing act that Savoca and Taylor pull off here, subtly shifting the audience’s perspective and sympathy to align with Rose. It’s also a move that takes the narrative further away from Comfort’s original script to center on the story of a teen girl’s romantic and sexual self-awakening.

Eddie Birdlace may think Rose Feeney an easy mark, but she proves to be a character of surprising depth and candor. While Eddie is a bullshitter, Rose is a straight-shooter. She may be naïve, but she’s forthright, self-possessed, and knowledgeable, especially about that what she loves most in the world: her beloved folk music. Dogfight is full of folk and protest music, from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and to early Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Van Morrison. More to the point, Rose believes that music—not war—can change the world. Even in padded wardrobe and prosthetics, Taylor may be too beautiful an actress to be credibly brought to a “dogfight,” but her character is earnest, sincere, and original. That she gives Eddie a second chance in the film may strike more of narrative contrivance than continuity, but it allows for an evening’s worth of tender, awkward, and realistic romance.

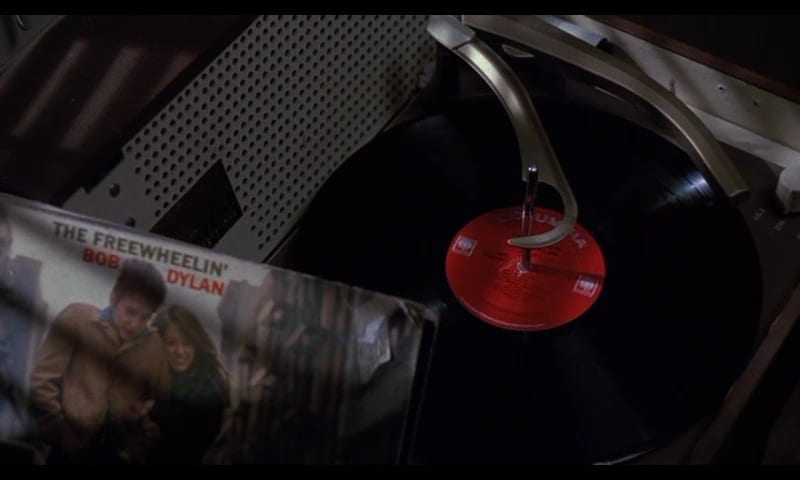

Nearly everything about Dogfight is unconventional, and its depiction of Rose and Eddie’s night of intimacy is no different. Their conversations are awkward, Rose’s nightgown spectacularly unflattering, Eddie’s bravado unable to cover his nervousness. Something nearly unprecedented in film romance occurs: he literally asks Rose’s permission. (Just months before, Time magazine’s coverage of the Katie Koestner case placed the phrase “date rape” in the public lexicon and initiated a decades-long and long-overdue national discussion of consent.) As the two gently, awkwardly snuggle, kiss, and eventually have sex, the camera pans to Rose’s record-player dropping the needle on The Freeewheelin’ Bob Dylan, its cover image of Dylan arm-in-arm with then-paramour Suze Rotolo on the streets of Greenwich Village suggesting Rose’s dream of an idyllic future.

The lyrics of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” cut deeper, exhorting Rose to live in the moment but also foreshadowing her lover’s leaving: “When your rooster crows at the break of dawn / Look out your window and I’ll be gone.” Just like Dylan’s lyrics predict, the next morning Eddie is gone. In quick order, Eddie lies to the B-Boys about a night out with “an officer’s wife”; Rose and her mother tearfully witness TV reportage of Kennedy’s assassination; and flashing forward to 1966, Eddie is stationed in Chu Lai, Vietnam, still together with the other B-Boys, when a sudden mortar attack interrupts a moment of camaraderie. This scene of combat is the only “war” in this war film, and it clocks in at just under a minute, a shocking, frenetic, bloody, and gruesome depiction of battle that leaves Eddie wounded—and, we learn later, his three friends killed in action. Dogfight may not be a combat film, but its protagonists are profoundly changed by war.

Dogfight’s ending reinforces the trauma both of its protagonists have experienced. Back on the streets of San Francisco, a limping Eddie is taunted by a hippie about killing babies. But he finds Rose’s café—it’s now hers, her mother having passed on—and the two of them reunite, nearly wordlessly. Here again Savoca’s direction is unconventional but compelling. Rose and Eddie hug, the camera alternating between over-the-shoulder close-ups of each as their eyes dart, then tear up. Years have passed since their one night together. Both actors flood the screen with emotion: passion, regret, trauma, pain. Savoca then cuts to a wider, higher perspective of the two of them, still in a silent embrace, for ten full seconds before a quick fade to black. The film’s conclusion leaves viewers with plenty of time and space to ponder the havoc the Vietnam War wrought on their lives and love.

So much of what I love about Dogfight is the willingness of Savoca, Taylor, Phoenix, and Guay to take the film in directions Comfort’s script hadn’t imagined. Or for that matter, that nearly any romance, coming-of-age tale, or war film of the time could. But those revisions, according to Savoca on her director’s commentary, displeased not only the scriptwriter but the studio as well. Warner Bros. tested the film in front of audiences who thought the “dogfight” concept was hilarious but the ending too ambiguous and downbeat. With Taylor and Phoenix unavailable to reshoot and unwilling to work with a replacement, Savoca stood her ground, and Warner Brothers released the film as shot—but with nearly no publicity to support it. What marketing existed pegged the film as a teen comedy, suggesting that the studio either misunderstood or willfully misrepresented its aims. After debuting at Telluride, the film was released in only 24 theaters and pulled in less than $400,000 in its domestic run.

An American film about war—or, at least, about a teenage girl’s thoughtful rejection of the misogynistic and militaristic ideologies informing it—directed by a woman was simply unprecedented in 1991. It would be nearly 20 years after Dogfight that Kathryn Bigelow would earn her Best Director Oscar for The Hurt Locker. In 1991 when Savoca directed Dogfight, just four percent of the 200 highest-grossing Hollywood productions were directed by women, a statistic that remained remarkably, regrettably static up until just very recently. Even in a year that featured films directed by Savoca, Bigelow, Mira Nair, Barbara Streisand, Julie Dash, and Jodie Foster, Dogfight was such an anomaly it’s not hard to understand its difficulty finding an audience.

With the benefit of hindsight, Dogfight makes for a very special kind of anti-war film. In privileging the perspective of its teen female protagonist it makes clear its feminist sentiments. In eschewing combat for tender, awkward romance it disrupts the common tropes of the genre. And in bluntly deconstructing the misogyny of military male bonding, it reinforces the value of women and family to men. And at the same time, Dogfight is a film that understands and even reveres what each partner can bring to the other even in a relationship defined by conventionally heteronormative, traditional gender roles.

Dogfight may be known today only as a River Phoenix film, especially for the late actor’s devoted completionists. And Phoenix is indeed excellent as the Marine whose misogynist bravado masks a more sensitive interior. Others may know Dogfight from the 2012 Joe Mantello Broadway musical starring Lindsay Mendez and Derek Klana with music and lyrics by Benj Pasek & Justin Paul of La La Land (and if you don’t, you might enjoy one of their marvelous performances available on YouTube). The film offers other small pleasures: folksinger Holly Near has a small role as Rose’s mother, Brendan Fraser appears briefly in his first credited film role (as “Brendon” Fraser), and E. G. Daily is marvelous in a brief but affecting role as the “dog” who reveals the truth of the game to Rose.

But even aside from its pointed antiwar stance and unique perspective, Dogfight still deserves a bigger audience. To estimate from box office receipts, during its 1991 opening, fewer than 80,000 viewers would have seen it in the theaters. It was for a time available on VHS and then as a WB DVD release, one with Savoca and Guay’s forthright behind-the-scenes commentary. But it never received a special edition or blu-ray remaster, much less a 4k release or any particular attention from festivals or revues. (A book about its making was aborted after its writer met with a stonewalling in the form of a potential lawsuit.) Fortunately, today Dogfight is at least available to rent on nearly every streaming service, and nearly 30 years out from its debut, it remains one of the most thought-provoking, heart-rending films I know. Dogfight may feature only a minute of combat, but its perspective on war—and on love—speaks volumes.

Dogfight is Nancy Savoca’s best work. I love this film and am so pleased that Professor Johnson has chosen to write about it. But I would pose a question about his comment about Kathryn Bigelow. Dogfight is a war film directed by a woman from the point of view of a woman’s sensibility that few if any men could make. I got lots of hate mail when I published a review in Salon.com saying that Bigelow’s film,The Hurt Locker, is a war film made by a woman as a man would make a war film. She imitated male choices well, but I found it ersatz. I still maintain that what I said is true. I would say that the difference between Savoca’s courage and integrity and Bigelow’s pandering choices is the reason that Beigelow got an Oscar and Dogfight is all but forgotten. I didn’t rejoice when she won, and I don’t regard it as a big first step for women. Ironically, both are now forgotten. Let that sink in. I hope this essay revives interest in Dogfight, a film with with a true personal vision.

Thank you for reading and for your comment. I agree Dogfight and The Hurt Locker are as different as night and day, their only connection the one I noted above. Both are “about” war (if in a loose sense) and both directed by women. Sorry about your experience with your article! Your take sounds pretty reasonable to me.

I feel like when Dogfight was released a Hollywood production about war and directed by a woman was unprecedented and nearly unimaginable. From Savoca’s commentary it sounds like Warner Bros had very little idea what to do with the film.

But Dogfight is a gem, isn’t it? I love the film. It needs a special edition rerelease or a retrospective somewhere to give it the credit it deserves!